A Brief History of New York Punk

On the tenth anniversary of Lou Reed's death, we celebrate the scene he started

Welcome back to Culture Club, a feature where David and I write about what we’ve been reading, watching, playing, and listening to, for paid subscribers. Please enjoy this free preview, and consider upgrading to support two struggling journalists at once! — Talia

From the moment I moved into my first (adult) New York apartment in the fall of 2000 until his death ten years ago this week, Lou Reed felt a bit like the fairy godfather of my downtown dreams. The apartment was on Grand and Ludlow in the Lower East Side, and at the time I was just starting an internship at Rolling Stone, where I quickly discovered that I was distressingly uncool. This was the same month that Almost Famous hit movie theaters, so being uncool at Rolling Stone had a certain romance, but it still came as an unwelcome realization. A working knowledge of the Velvet Underground canon was the bare minimum requirement; let’s just say the staff’s definition of cool was not the same as the owner’s, whose music taste was a lot closer to my own at the time.

What I needed was a crash course in cool, and Lou Reed would be my teacher. Admittedly, I approached my studies like a teacher’s pet, taking a distinctly uncool approach in my quest for coolness. I obsessed over his music, and read everything I could get my hands on. Among other things, I learned that on the very same Lower East Side block I was now calling home, Lou Reed had founded the Velvets thirty five years before (his next apartment was on East 10th, the street I grew up on.) In the fall of 2000, the Lower East Side music scene was starting to catch fire, and Reed’s sooty fingerprints were everywhere.

Over the last few months, I’ve been thinking a lot about Lou, about the scene he ignited, and about the time in my life when I discovered it all. In early October, “Lou Reed: The King of New York” by Will Hermes was published, and it paints a meticulous portrait of the artist, blemishes and all. Reed may have been a genius, but he was a heroically cantankerous one. To say that he didn’t suffer fools would be an understatement, and he considered most journalists to be quite foolish indeed, (a fact for which we have Lester Bangs to thanks, according to Hermes.)

I learned this firsthand when I interviewed Reed in 2004. It was a mildly traumatic experience, not because he was at angry at me, exactly, but because he was angry in general—in the priggish wake of Janet Jackson’s Super Bowl performance that year, Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” had been dropped from radio playlists. As he raged against the powers that be, demanding to know how the hell America had reached such a sorry state of affairs, I found myself up against the ropes, sweating profusely, trying desperately to answer his rhetorical questions. It was trial by Lou.

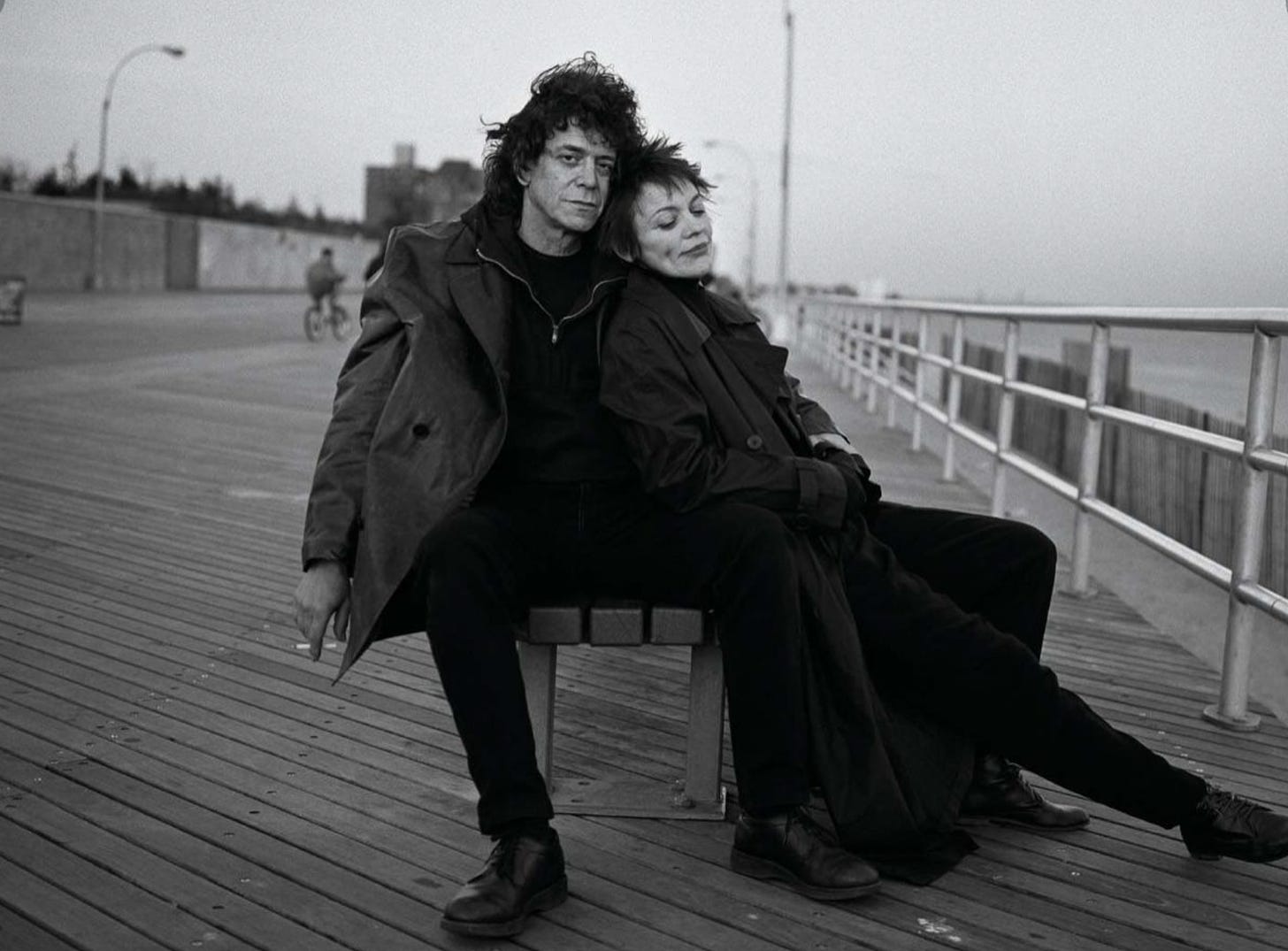

But by 2004, I was also aware that he had a soft side. One of my best friends worked for one of Lou’s best friends, and I knew how tender he could be with his loved ones. In those years you’d often spy him out and about at concerts and art openings, on the arm of his wife, Laurie Anderson: the King and Queen of downtown New York. Hermes details all of this in his massive biography, a worthwhile read for any fan, and one I really could have used two decades ago.

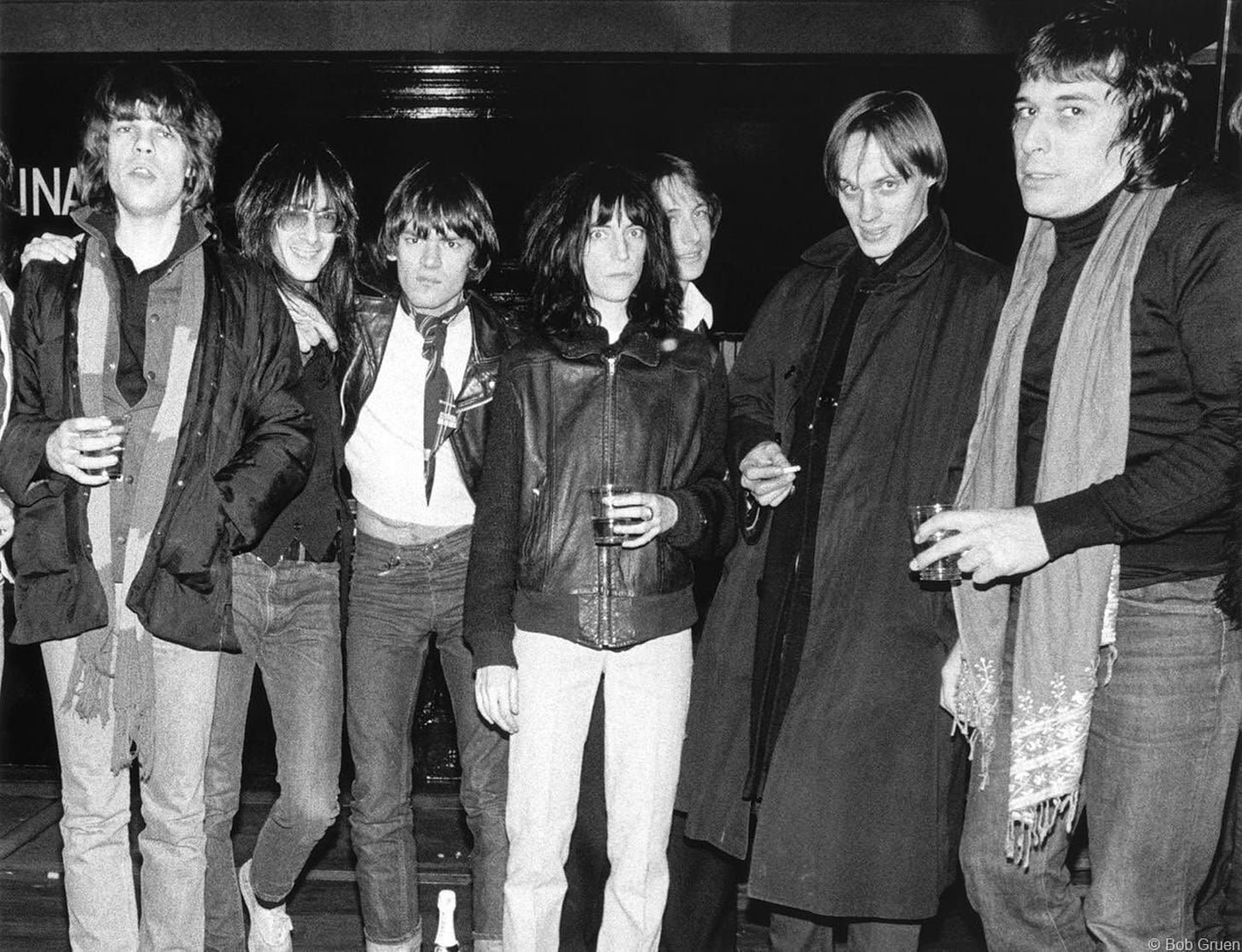

The book, and the anniversary of Reed’s death, inspired this week’s culture column, in which I dig into the archival record of his career, and the scene he and the Velvets ignited. It covers almost fifty years, from Reed’s arrival in New York in 1965 until his death on October, 27, 2013. Along the way, the New York Dolls flamed up and out, CBGBs opened and closed, and artists such as Patti Smith, The Ramones, Television, Blondie, and Talking Heads led a rock revolution.

In addition to stories about these artists, I’ve also included several by them: Patti Smith on Television, Richard Hell on the Ramones; Kim Gordon on touring with Sonic Youth; Lou Reed on touring as a wizened punk elder; Patti Smith, again, on Reed’s passing. For anyone looking for deeper first-hand accounts of this chapter in New York history, Hell, Smith, and Gordon have all written movingly about their own experiences. And as much as I enjoyed Hermes’ account, I wish Reed have lived long enough to tell his own story, the way some of his contemporaries did. He was a writer at heart. “Lou brought the sensibilities of art and literature into his music,” wrote Smith in 2013. “He was our generation’s New York poet.”

My First Year in New York; 1965

By Lou Reed

New York Times Magazine, September 17, 2000

I slept in a used Navy peacoat and did what laundry I had at a dealer's house on East Sixth Street, until a jealous lover shot my friend's leg off with a shotgun blast through the door. This caused some consternation in our crowd, and eventually eight of us banded together and moved en masse to a new apartment on Grand Street. There I slept on a small cut-up mattress that rested on the floor. It made me nervous because we had rats and I worried about being bit. At this point the Velvet Underground had sprung into being. The junkies who lived below us honored our first job by robbing the entire band of everything that was not with us at the gig.

Notebook for Night Owls: The Velvet Underground

By Sally Kempton

Village Voice, April 14, 1966

Andy Warhol’s new discotheque seems to be an attempt to instill permanence into a private joke. Presided over by the Velvet Underground, and decorated with colored lights, slides and films, it occupies a long mirrored room atop the Polski Dom on St. Mark’s Place, and has the air of a dancing party out of “The Masque of the Red Death.” Most discotheques seem to have been constructed around Sartre’s famous principle that hell is other people, but Warhol, being an innovator, has gone further than other entrepreneurs. He has so arranged his discotheque that his patrons tend to feel, after five minutes in the place, that they have wandered into some evangelist’s vision of Nineveh and that perhaps it is time to mend their ways.

Dead Lie The Velvets Underground R.I.P.: Long Live Lou Reed

By Lester Bangs

Creem, May 1, 1971

Now the time was finally on for the Velvets, rock'n'roll princes right out of history if ever once seen clearly, and Lou Reed, non-poseur poet-craftsman that could become a Dylan for the 70's without even becoming self-conscious about it. The public was tired of its arch-superstars with their identical, impersonal funk-laden albums, their arrogant concert boredom and charisma of distance.

The Velvets went in and recorded. Slowly and at ease for the first time, learning. Holdups. Rumors that the producer (Adrian Barbour, maybe) wasn't showing up for sessions all that regularly. Some vague conflict. Other rumors had the album finished, the Velvets dissatisfied, back for more work.

Perfectionist. Meanwhile there's some several thousand crazy kids (Velvet fans ain't no Mongol horde, but they'd rip the locks from doors and doors from jams to hear that music) out there across Southern California and the Corn Belt and up haulin' hod in North Dakota all jumpin' in ecstasy waitin' on the next big blast of Long Island sireen thunder.

New York Rock

By David Marsh

Creem, December 1, 1973

The back room at Max’s is a dimly lit, red-table-clothed, 20 x 20 foot den of iniquity. The food’s not much, and the drinks aren’t cheap, but no one really goes there to drink or eat; they go to see and be seen. On a given night in the middle ’60s, the legend says, almost any fabulous combination was possible: Mick Jagger, William Burroughs, Andy Warhol, Truman Capote and Germaine Greer, perhaps. To a lesser extent—because NY’s scene is less volatile these days—that is true today, though you are much more likely to see Todd Rundgren, David Johansen of the Dolls, too many rock writers and a sprinkling of semi-famous artists than any of the above. After 1 a.m., that is. Before, the front of the bar is crammed with suburban glam-ettesi, wondering why the stars aren’t there. (In the afternoon, in a switch which could happen only in New York, Max’s is a rather straight businessman’s lunch joint.)

Television: “Somewhere Somebody Must Stand Naked”

By Patti Smith

Rock Scene, October 1974

They came together with nothing but a few second-hand guitars and the need to bleed. Dead end kids. But they got this pact called friendship. They fight for each other so you get this sexy feel of heterosexual alchemy when they play. They play real live. Dives, clubs, anywhere at all. They play undulating rhythm like ocean. They play pissed off, psychotic reaction. They play like they got knife fight in the alley after the set. They play like they make it with chicks. They play like they're in space but still can dig the immediate charge and contact of lighting a match.

Tom and Hell started a forest fire in Alabama. They got sent up for watching it burn. Then they decided to burn themselves. No image of an image. The image itself. Billy always is laughing. Lloyd jacks off on his guitar. Hell is male enough to get ashamed that he writes immaculate poetry. And Tom Verlaine lives up tho the initials TV. He is a powerful image worthy of future worship.

Valley of the New York Dolls

By Paul Nelson

Village Voice, May 26, 1975

The first time I laid eyes on the New York Dolls, they were drunk in a Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith outside the terrace of the Dancers. David Johansen had lost the high heel from one of his shoes. He said, “I not only accept loss forever, I am made of loss,” while inside the club, the group’s managerial brain trust planned the conquest of blue dawns over racetracks and kids from sweet Ioway. The rest of the band—Johnny Thunders, Syvain Sylvain, Jerry Nolan, Arthur Harold Kane—talked happily about early days spent practicing in a bicycle shop near Central Park. And me? I’m a fool. My heart went out to the hopeful sounds. We all thought the group would achieve success through the purity of their rock ‘n’ roll art.

A Conservative Impulse in the New Rock Underground

By James Wolcott

Village Voice, August 18, 1975

These bands don’t have to be the vanguard in order to satisfy. In a cheering Velvets song, Lou Reed sings: “A little wine in the morning, and some breakfast at night/Well, I’m beginning to see the light.” And that’s what rock gives: small unconventional pleasures which lead to moments of perception.

Flashes like: the way Johnny Ramone slouches behind his guitar, Patti Smith and Lenny Kaye singing “Don’t Fuck With Love,” on the sidewalk in front of CBGB’s, the Shirts shouting in unison in their finale number, Tina Weymouth’s tough sliding bass on “Tentative Decisions,” the way Tom Verlaine says “just the facts” in “Prove It.” One’s affection goes out to Lou Reed, for such moments are like wine in the morning. Shared wine.

‘Gonna be so big, Gonna be a star, Watch me now!’

By Tony Hiss and David McClelland

New York Times, December 21, 1975

The very sight of Patti on stage evokes images of rock history—shaggy black hair like that of Keith Richards, pegged black pants like those of the young Bob Dylan, and a high‐strung youthful defiance that harks back to dozens of hard‐rock hopefuls in local clubs in the late 50's and early 60's. But she also sometimes looks like a pretty little girl, and all the influences are fused into a presence that is instantly recognizable as original. She talks her songs in places, but when she sings she has good pitch, good breath control and command of a full range of tones—sharp, rasping, round.

Lou Reed Rising

By James Wolcott

Village Voice, March 1, 1976

The Velvets and their progeny are all children of Dr. Caligari—pale-skinned adventurers of shadowy city streets. Richard Robinson, author of The Video Primer, has a video tape which shows Lou Reed and John Cale rehearsing for a concert to be performed in Paris with Nico. After Reed runthroughs “Candy Says,” they perform “Heroin” together: Reed’s monochromatic voice, Cale’s mournful viola, the dirgeful lyrics (“heroin … be the death of me …”), the colorless bleakness of the video image … a casual rehearsal had become a drama of luminous melancholia. What was blurry before became indelibly vivid, and the Reed/Cale harlequinade melted away so that one could truly feel their power as prodigies of transfiguration. For them—as for Patti Smith, Eno, Talking Heads, and Television—electricity is the force which captures the fevers, heats, and dreamily violent rhythms of city life, expressing urban disconnectedness and transcending it. Electricity becomes the highest form of heroin … listening to the Velvets, you may have been alone, but you were never stranded.

Talking Heads: Cool in Glare of Hot Rock

By John Rockwell

New York Times, March 24, 1976

New York is caught up in an eruption of underground rock‐and‐roll bands at the moment, and the center of the scene is CBGB's, an almost deliberately tacky bar at 315 Bowery. Most of the bands that play there fit into the post‐Velvet Underground stylized punk school—black leather jackets or lyrics about drugs and sadomasochism or screamingly loud, twanging, three‐chord guitar rock.

In the midst of all this, Talking Heads stands curiously alone. The three members—David Byrne, lead singer, song writer and guitarist; Martina Weymouth, electric bass, and Chris Frantz, drums—stand there on stage looking almost preppy cool. The two men tend toward the kind of T‐shirt that has little alligators on them; Miss Weymouth generally sports stylish jumpsuits. Yet their look is just penetrating and strange enough to make one wonder how straight they really are.

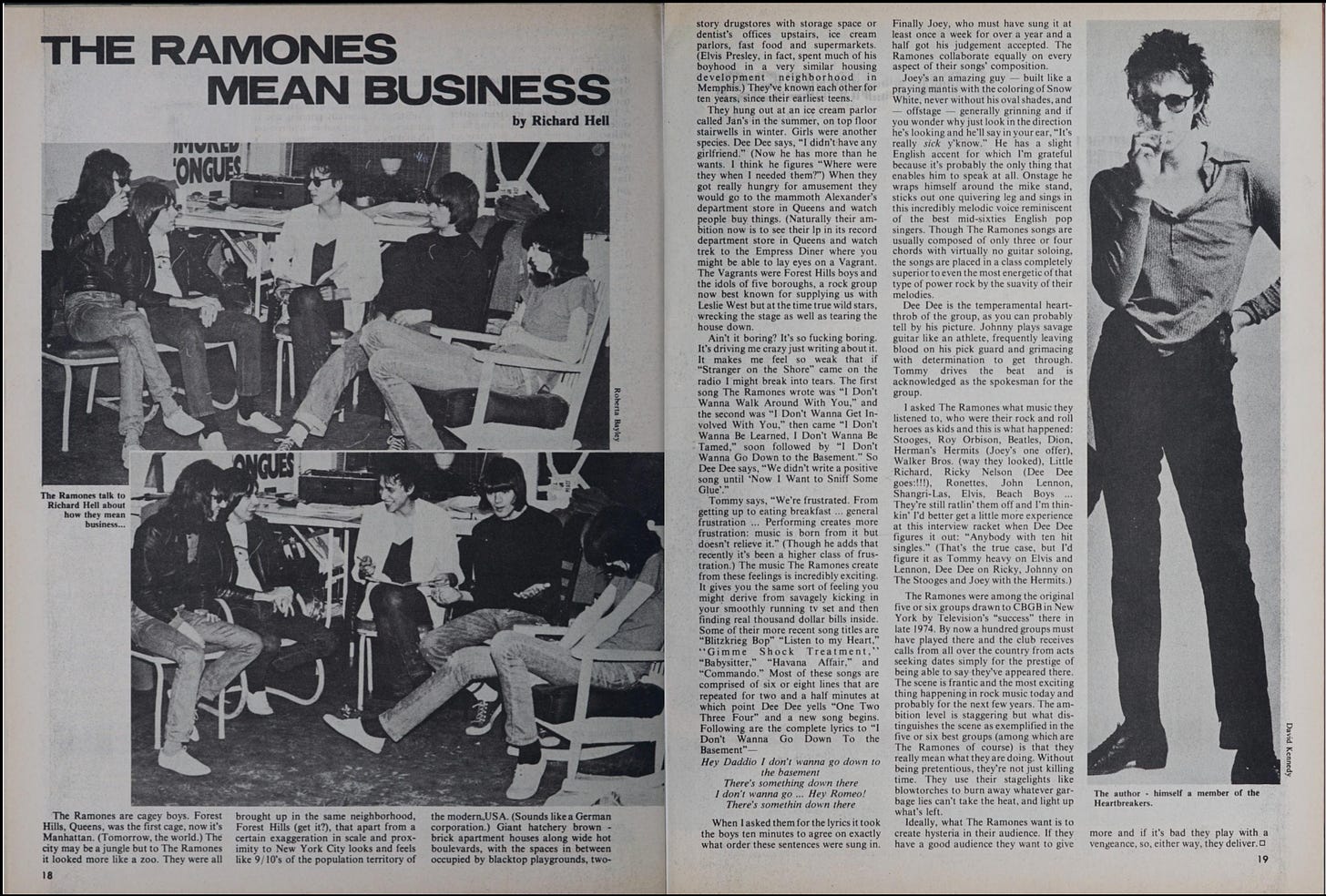

The Ramones Mean Business

By Richard Hell

Hit Parader, June 1976

The Ramones are cagey boys. Forest Hills, Queens was the first cage, now it’s Manhattan. (Tomorrow, the world.) The city may be a jungle but to the Ramones it felt more like a zoo. They were all brought up in Forest Hills, a neighborhood that apart from a certain exaggeration in scale and proximity to New York City looks and feels like 9/10th’s of the populated territory of the modern USA (sounds like a German corporation). Big hatchery brown brick apartment houses along wide hot boulevards, with the spaces in between occupied by blacktop playgrounds, two story drugstores with storage space or a dentist’s offices upstairs, ice cream parlors, fast food, and supermarkets. (Elvis Presley, in fact, spent much of his boyhood in a similar housing development neighborhood in Memphis.) They’ve known each other for ten years, since their earliest teens.

Punk is Just Another Word for Nothin’ Left to Lose

By Mary Harron

Village Voice, March 28, 1977

Although Patti Smith had toured England long before the Ramones arrived in London in July of last year, it was Ramones’ reverberations which were felt on the British scene. Because the myth of punk rock was that it was a cohesive movement, the English fans assumed that other New York bands like Television and Talking Heads were cast in the Ramones mold. Everyone wore black leather jackets and played lightning-fast four-chord rock ‘n’ roll.

I can’t say what went on in the minds of that first London audience, but I suspect that they took the Ramones more seriously than the Ramones took themselves: took them to be bored, sneering, dead-end kids. After all, the image of New York that flickers through television and the movies is of the asphalt jungle. You have only to read the English papers to see that it’s not just rock fans who take their visions of America from Kojak and Taxi Driver. Manhattan has a mythology all its own.

Legs McNeil: Teenage Hipster in the Modern World

By Mark Jacobson

Village Voice, August 7, 1978

The CBGB rock scene had disintegrated before Legs’s eyes. Many of the first-generation bands, the ones Legs thought spoke for him—Talking Heads, Ramones, Blondie, and the Dictators—got recording contracts and went away on tour. Legs was all for that. Hipster punks knew that the popular culture created them. And they were determined to do something—anything—to make their mark on it. The bands, Legs and Holmstrom figured, were the best bet to express “teenage” obsessions. The media never seems to outgrow its need for rock and roll. Sooner or later, Legs thought, the punk bands had to become the next big thing.

The Importance of Being a Ramone

By Timothy White

Rolling Stone, February 8, 1979

Where did your American eagle logo come from?

Johnny: I don’t know if what we’ve got is the American eagle, but that’s what we thought of at the time.

Dee Dee: It looks good up there. I mean, Patti Smith has the American flag . . .

Johnny: ... and we have a kind of presidential seal.

Marky: Yeah. “In God We Trust.”

Joey: [Snickering] We weren’t thinking of God.

Johnny: You want a strong symbol, and that’s it.

Dee Dee: [Earnestly] We want to make it clear that it has nothing to do with fascism or anything like that.

Johnny: [Alarmed] Nobody asked ya!

Dee Dee: [Continuing] It’s just a sign that I think …

Johnny: [Firmly] Nobody asked ya!

The White Noise Supremacists

By Lester Bangs

Village Voice, April 30, 1979

Richard Hell and the Voidoids are one of the few integrated bands on the scene (“integrated”—what a stupid word). I heard that when he first formed the band, Richard got flack from certain quarters about Ivan Julian, a black rhythm guitarist from Washington, D.C., who once played with the Foundations of “Build Me Up Buttercup” fame. I think it says something about what sort of person Richard is that he told all those people to get fucked then and doesn’t much want to talk about it now. “I don’t remember anything special. I just think that most people that say stuff like what you’re talking about are so far beneath contempt that it has no effect that’s really powerful. Among musicians there’s more professional jealousy than any kind of racial thing; there’s so much backbiting in any scene, it’s like girls talking about shoes. All musicians are such scum anyway that it couldn’t possibly make any difference because you expect ’em to say the worst shit in the world about you.”

Platinum Blondie

By Jamie James

Rolling Stone, June 28, 1979

As for Debbie Harry herself, the underground “punk Harlow” is not only a bright new star, but also the first rock pinup in recent memory. Since Blondie’s inception in 1975, Debbie has been a fashion trend-setter as well as a sex symbol. She contributed to the vogue of the thrift-shop look as much as anyone, once appearing onstage in a tacky wedding gown and telling the audience, “It’s the only dress my mother wanted me to wear.” Joan Rivers goes punk.

At that time, Patti Smith was the other big female rock star in New York. Patti’s bedraggled guttersnipe look was much more fashionable in those circles. There was pressure on Debbie to go dirty, but she stuck by her miniskirts and spike heels. With the passing of hard-core punk, it was Debbie’s campy, Sixties nostalgia trip that came out on top, the strong visuals complemented by some of the best rock on the radio in a good long time. As Debbie warns in the band’s new single: “One way or another, I’m gonna find ya/I’m gonna getcha, getcha, getcha, getcha.”

Richard Hell: An Antidandy at the Peppermint Lounge

By Robert Christgau

Village Voice, July 27, 1982

At the time of “Blank Generation,” Hell really was the quintessential avant-punk. With no more irony than was mete, he presented his nihilistic narcissism not as youthful hijinx but as a full-fledged philosophy/aesthetic, and though he never quite put his heart into proselytizing, he was perfectly willing to go along with impresarios who considered his stance commercial dynamite—and to con others when the money ran out. Nor was he merely purveying a stance. Though it was the musicianship of Bob Quine—a much denser, choppier, and more nerve-wracking player than his romantic rival, former Hell associate Tom Verlaine—that made the Voidoids the most original and accomplished band of the CBGB era, Quine was and is a sideman, worth hearing in any context but lacking the visionary oomph to create one. The band was Hell’s.

Boys Are Smelly: Sonic Youth Tour Diary, ’87

By Kim Gordon

Village Voice, September 1, 1988

In the middle of the stage, where I stand as the bass player of Sonic Youth, the music comes at me from all directions. The most heightened state of being female is watching people watch you. Manipulating that state, without breaking the spell of performing, is what makes someone like Madonna all the more brilliant. Simple pop structures sustain her image, allowing her real self to remain a mystery—is she really that sexy? Loud dissonance and blurred melody create their own ambiguity—are we really that violent?—a context that allows me to be anonymous. For my purposes, being obsessed with boys playing guitars, being as ordinary as possible, being a girl bass player is ideal, because the swirl of Sonic Youth music makes me forget about being a girl. I like being in a weak position and making it strong.

The Aches and Pains of Touring

By Lou Reed

New Yorker, August 18, 1996

SATURDAY, JULY 20TH • Travelling from Prague to Vienna to Zeebrugge, Belgium. Two connecting flights and a one-hour layover. Travel time: six and a half hours. Playing time: one hour. My luggage is lost. An interviewer asks me why I don't smile much. I wonder if he'd ask Miles Davis that question. I tell him to check my inner glow. Some group has threatened to kill the Sex Pistols for cancelling a gig—security is high. What a way to go. Shot by a drunken fan mistaking you for Johnny Rotten. I love rock and roll.

Lou Reed

By Patti Smith

New Yorker, November 3, 2013

As news of Lou’s death spread, a rippling sensation mounted, then burst, filling the atmosphere with hyperkinetic energy. Scores of messages found their way to me. A call from Sam Shepard, driving a truck through Kentucky. A modest Japanese photographer sending a text from Tokyo—“I am crying.”

As I mourned by the sea, two images came to mind, watermarking the paper-colored sky. The first was the face of his wife, Laurie. She was his mirror; in her eyes you can see his kindness, sincerity, and empathy. The second was the “great big clipper ship” that he longed to board, from the lyrics of his masterpiece, “Heroin.” I envisioned it waiting for him beneath the constellation formed by the souls of the poets he so wished to join. Before I slept, I searched for the significance of the date—October 27th—and found it to be the birthday of both Dylan Thomas and Sylvia Plath. Lou had chosen the perfect day to set sail—the day of poets, on Sunday morning, the world behind him.

Fantastic. What memories, beautifully written , David!