Anatomy of a Con: The Mark

The targets of right-wing scams will empty their bank accounts to try to make the earth stand still

Edited by David Swanson

Last week was the anniversary of one failed coup, and the beginning of another. As the angry crowds milled through clouds of tear gas in Brasília, as they’d done two years ago in Washington, D.C., I thought about the people who’d sold them that dream of vengeance, and how much money they’d made along the way.

I’ve been thinking a lot about grifts, lately: how they work, and how the two material pieces of the puzzle—the con man and the mark—fit together. The dance of deception requires two partners at least; without its supporting blocks, a pyramid scheme would crumble; a siren song dies in the throat when there’s no one there to hear it.

Most accounts of deception focus on the scammers, for obvious reasons, from the excitement of watching someone get away with bad things to the inherent thrill of deceit. I watched Catch Me If You Can (and read Frank Abagnale, Jr.’s workmanlike memoir of the same name) with the kind of throb in the temples that usually only horror evokes. Witnessing a man painstakingly fabricate credential after credential, fake his way through the most august of professions on cojones alone, was a thrumming little spike to the adrenaline, even from the safety of a movie-theater seat. Less inspiring than the slick figure in the rented uniform, perhaps, is the sucker who takes the bait: some schmoe, hoping for a quick buck, or little love, or a cure for whatever ails him. Faith is just as crucial a component of the swindle as anything else, the cruel coda to the story of Pandora’s box. What we hope for can hurt us as much as anything else, and sometimes much worse.

“Cons thrive in times of transition and fast change, when new things are happening and the old ways of looking at the world no longer suffice,” writes Maria Konnikova in her book The Confidence Game, which examines the psychology and history of con artistry. “That’s why they thrive during revolutions, wars and political upheavals…There’s nothing a con artist likes better than exploiting the sense of unease we feel when it appears the world is about to change.”

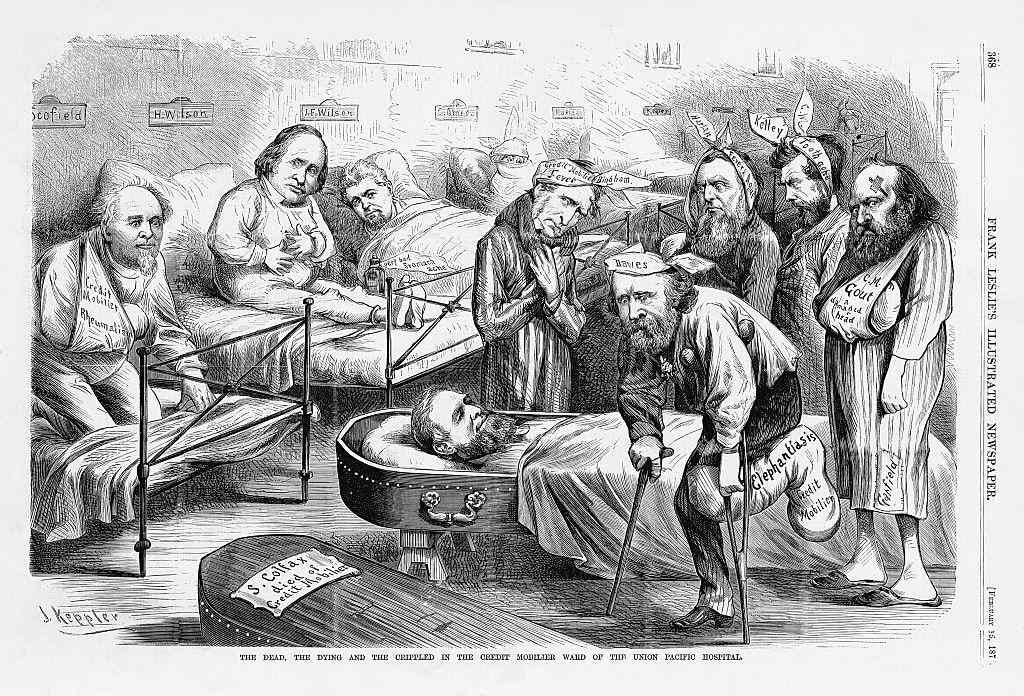

Thus the proliferation of scams around the gold rush in 1849, the relentless westward expansion of the United States, the various transformations of the Industrial Revolution. One of the biggest financial rackets in the nation’s history involved Crédit Mobilier of America, a sham corporation established to help build the Transcontinental Railroad a century and a half ago. Transition begets unease, unease begets a desire for certainty, and the more frenetic that desire, the more even the appearance of suavity and confidence wins unearned trust, and ill-gotten gains.

What makes contemporary right-wing con jobs such stellar examples of this axiom is that the politics they exploit are the direct result of the fear of change. Conservatives as a whole skew older and whiter than the population at large, and so they tend to consider themselves the people who have the most to lose from societal shifts. This position offers an inherent vulnerability to fearmongering about the future. It’s particularly oriented around an overt hostility to subsequent generations’ threatening mores, from interracial relationships to subversion of gender norms to a tendency towards socialism. In an age in which the dog whistle has largely been abandoned in favor of the bullhorn, there is a great deal of money to be made in the scapegoating industry, and still more in the arena of the alleged great fight for the soul of Western civilization.

This results in all kinds of profit, including the penny-ante, embarrassing shtick. Consider, for example, Jodi Shaw, a Smith College librarian who dramatically announced that she was leaving her job due to an environment that had become “racially hostile” to white people. Among the chief examples she offered was an administrator’s negative reaction to rap song she wrote (and subsequently, voluntarily, and without in any way being waterboarded into it or anything, posted to the Internet). Her claims of anti-white college-campus prejudice were so compelling to the anti-cancel-culture crowd that she raised more than $300,000 to, among other things, file a white-civil-rights lawsuit against Smith in 2021 and launch a nonprofit for “artists whose voices have been stifled.” The nonprofit’s website, which was “under construction” as of June 27, 2021, does not exist yet.

Shaw may have raised a small fortune on GoFundMe, but she was only able to do so because of the robust armature of of conservative grievance, which is perfectly happy to fan fears of anti-white racism, baselessly accuse gay and trans schoolteachers and children’s book authors of pedophilia, and make a bundle doing so. This is a multimillion-dollar industry, and while it isn’t an overt grift, per se—Bari Weiss’ newsletter may be a vile collection of calumnies and distortions, but it isn’t any more of a scam than this one, even if it makes a great deal more money—it is both adjacent to grift and eager to perpetuate it. (Shaw made her great hip-hop debut on Weiss’s Substack, one of many eager to claim martyrdom for “wrongthink,” and is neither the first nor the last to make a pile fundraising off self-inflicted wounds.)

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

But here I am—focusing on the con again, ignoring the mark. I admit I am not particularly eager to contemplate the psychology of the average Bari Weiss superfan, but failing to do so is to ignore a shiver rippling across the nation’s flesh. It’s the restless ire of those who ceaselessly, insatiably hunger to justify their bigotry and their fear; those who want, above all else, to be soothed by a sense of righteousness. They are legion and have deep pockets, and industries have sprung up around them, from the Florida Keys to Southern California, and myriad less sunny places in between. They are as inevitable as the progress of a railroad; they march through like steel tracks, scarring the landscape as they go.

How you feel about all this depends in part, I suppose, on your definition of grift: are overtly fraudulent claims required, or do vibes-based grievances suffice as a premise for fundraising? Do sham products have to be rustled up, ponzis schemed, castles built on clouds—or is the mere fundamental misrepresentation of reality enough to qualify as a scam? If the former, the American right is absolutely riddled with enough supplements that turn you blue or claim to make your brain function at wizard level to more than do the job. If the latter, well … there seems to be no bottom at all. Which is always a live possibility, when broaching this realm.

If Shaw and her ilk offer the intellectual equivalent of Sweet’n’Low for the right—all sweetness, no substance, delivered in a neat little packet—then there are plenty of vendors at conservative conferences, GOP campaigns stops and right-wing publications which offer things to eat, wear and inject in order to supercharge the body. “Glyconutrients, or neutraceuticals—health supplements that promise almost miraculous results—are constantly being pitched to conservatives by voices they trust,” wrote Washington Post reporter David Weigel in a 2015 piece on Ben Carson’s supplement side hustle that by now feels almost quaint. It’s eight years later, and things have progressed to anti-vaxxers treating their Covid symptoms with bleach enemas, and selling USB keys with stickers on them claiming to be “quantum holographic shields” against 5G radiation. The health-scam, disaster-prep, and right-wing paranoia worlds overlap so neatly the Venn diagram resembles a stack of pancakes.

Nothing exemplifies this better than NaturalNews.com, a supplement-sales site turned media empire whose traffic is in the millions of pageviews per month and whose recent headlines include “Comet impacts, pre-Adamic civilization, lost worlds and the Luciferian WAR against humanity” and “The America we grew up in is already gone—what remains is some sick, perverted leftist version of the twilight zone where people now identify as cats and dogs.” You can buy black cumin seed oil, colloidal silver nasal spray, and SurThrival Immortality Quest Chaga Mushroom Extract ($64/50ml) on the site, too, once you’ve finished learning how to prep for the Luciferian war.

The commonality in all this is fear: the sensation of it, the stoking of it, the rage it generates. Like any strong emotion, fear creates an opening. To interrogate the mark, we have to backtrack from the con. The person who seeks mushroom powder to secure immortality, the person afraid of the devil’s war, the person who damns his country as full of delusional dog people is a fearful one, and a rageful one. It’s someone who fits Konnikova’s definition of a mark perfectly: filled to the skin with unease at change, and ready to drown all skepticism in the assurances of others.

Fear isn’t sexy—it doesn’t make good copy like scams do. But it is a motive force as strong as lust, as ubiquitous as hunger. The marks of right-wing cons will empty their bank accounts to the last penny in an effort to try to make the earth stand still. It doesn’t, it hasn’t. Even the prophet Joshua only got the sun to pause in the sky, and only once. But terror is a gap so wide even the clumsiest of conmen can stroll right through, carrying a hatful of promises, a sack of black seeds to plant in the fear-lush heart.

Thank you for this piece, it does a fine job of articulating why it is so important to investigate why the same type of con works over and over in just slightly different forms. The mark is such an integral part of the con that it seems ridiculous to overlook them during the dissection of a successful con job. I'm sure that all of us know, or have family, who have been suckered in to believing a narcissist's fearmongering to the point that they cannot see the truth that is right in front of them.

An epic post. I just can't grok people who fall for these scams, but as I read in one of the Rick Perlstein's books, the direct mail works disproportionately well for the Conservative universe, and Richard Vigueries (sp?) was an early innovator. One thing that I was stunned by was how much money these scam's bring in, and how little of it ended up for the original, purported intent.

That really warps my brain.