Back in November 2020, when Donald Trump was still president and covid-19 vaccines were months from reaching American arms, one TikTok user went viral for her belief that the shots would signal the end of the world. Taylor Rousseau, a platinum-blonde, blue-eyed devout Christian TikToker, turned up the moody, throbbing strains of James Arthur’s Christian anthem “Train Wreck,” and carried out a one-woman, forty-second theological melodrama. In a red hat and impeccable makeup, she plays a martyr who refuses a vaccine — complete with microchip — mandated by murderous state authority. She’s beaten to death (the blood is ketchup, the mascara smeared) for that refusal, teleporting to the Pearly Gates, where God (in a very large font) declares “Well Done, Good and Faithful Servant” (sic). The tag on the video? “#pov you're required to take the mark of the beast (vaccine) or you die, but you know what Gods word says so you deny it ❤️"

The video, a hot and ferocious mess, spread wildly, spawning legions of imitators and parodies. The vaccine wasn’t an operative reality, yet — we were still hovering in the cureless-plague era, a miasma of fear and restriction and death, offscreen, in overcrowded ICUs — but already someone had slotted it into eschatology, predicting the end of the world in a time of literal cataclysm. There was already a plague, and locusts were despoiling whole countries. Time felt warped and strange and heavy. Maybe it really was the end of the world.

The concept of the “mark of the beast” is derived from a gnomic passage in the Book of Revelation, the final book of the New Testament:

[16] And he causeth all, both small and great, rich and poor, free and bond, to receive a mark in their right hand, or in their foreheads:

[17] And that no man might buy or sell, save he that had the mark, or the name of the beast, or the number of his name.

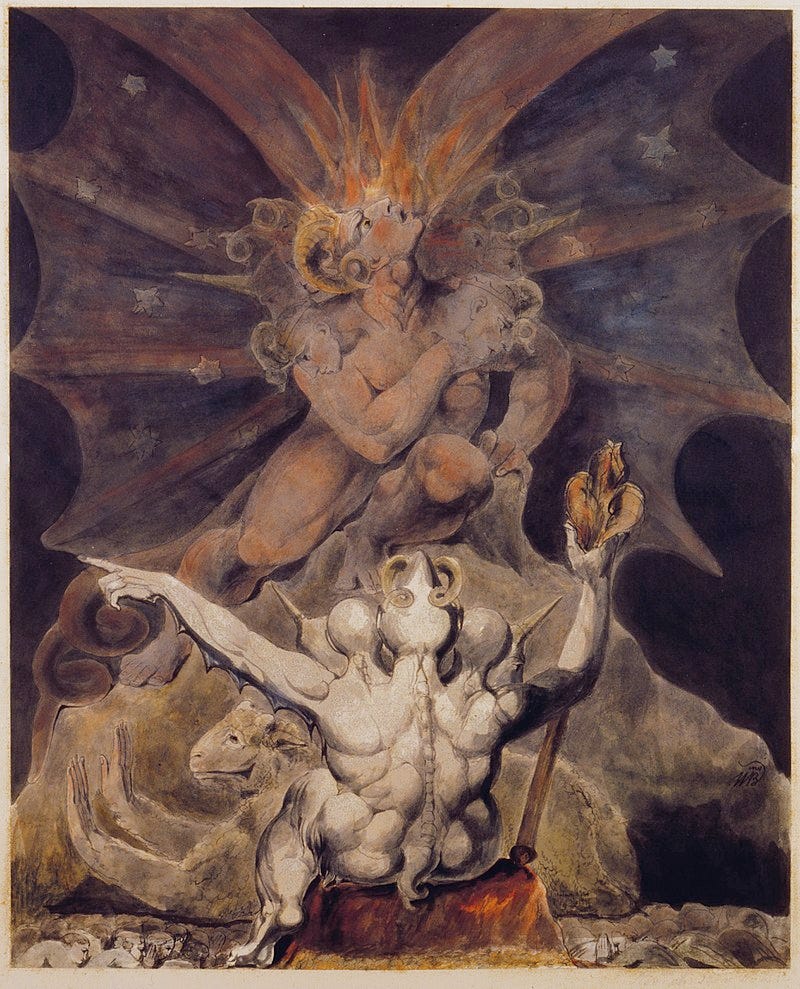

“The number of the beast is 666,” by William Blake, c. 1805

In Revelation, the mark of the beast distinguishes the faithful from the faithless; those who reject it, even on pain of death, will be among Christ’s elect. While that idea clearly has a lot of staying power, it’s been a very long time since 90 CE, when John of Patmos most likely composed his ominous vision of evil dragons, blood-drinking whores, golden girtles and cryptic numerology (ominously numbered heads, horns, candlesticks, wings, etc.) The book has been a point of contention throughout Christian history — it was a late and controversial addition to the biblical canon; Martin Luther used it as a rhetorical weapon against the Vatican, which responded in kind. But despite its long and dramatic past, many American Evangelicals consider Revelation to be a deeply contemporary and urgent vision.

The latest manifestation, the idea that the Covid-19 vaccine is the fabled “mark of the beast,” has exploded with the arrival of widespread vaccine rollouts and mandates. Two TikTok hashtags, #MarkOfTheBeastIsTheCovid19Vaccine and #VaccineIsTheMarkOfTheBeast, reached some 700,000 views earlier this year before being banned by the service. An RNC official in Florida declared that Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer was acting as a servant of Satan, forcing her constituents to get the mark in the form of the vaccine. Kanye West echoed the claim. “That’s the mark of the beast. They want to put chips inside of us, they want to do all kinds of things, to make it where we can’t cross the gates of heaven,” he told Forbes in July. The view has cycled through far-right Internet spaces, particularly on Trumpist forums and white-nationalist-friendly sites like the heavily Christian and deeply racist Twitter clone Gab. Though it’s difficult to poll for such an esoteric belief, public figures and publications across the country have felt a need to address it, consulting healthcare workers, pastors or (in the Oklahoman’s case) a “Biblical prophecy expert” with intimate knowledge of the end of the world.

The Sword and the Sandwich is an exploration of deadly serious extremism and also very serious sandwiches. To support this ongoing work and access all future content, please consider a paid subscription:

Christian eschatology — under the aegis of a nineteenth-century philosophy with the unwieldy name of “premilleniarian dispensationalism” — looms large in the American evangelical mind; according to a Pew poll from 2010, a full 41% of Americans expect Jesus Christ to return by 2050. (“Premillenarian” refers to the belief that Jesus will return physically to earth before the prophesied Millennium, a thousand-year reign of holy peace predicted in Revelation. “Dispensationalism” is the concept that time is divided into separate eras, or dispensations, with the final dispensation — the Rapture and subsequent bloody, fearsome seven-year period leading up to the end of the world — yet to come.)

Crucially, the core of this belief system is the notion that all biblical prophecy is not only entirely literal, it is, to quote Tim LaHaye, co-author of the ultra-popular Left Behind series that dramatized the End Times in the 1990s, “history written in advance” — referring not to any of the events of the past, but exclusively to things that have yet to occur. Many scholars, by contrast, view Revelation as a thinly veiled critique of the Roman Empire, with the “mark of the beast” referring to likenesses of the Emperor Nero on imperial coins, seals and stamps. Supporting this thesis is the much-touted Scriptural companion to the mark of the beast — “the number of the beast,” 666, as laid out in Revelations 13:18: “Here is wisdom: Let him that hath understanding count the number of the beast, for it is the number of a man; and his number is six hundred threescore and six.”

666 has been a gold mine for pattern-seekers across time (at one point or another, the “man” in question has been theorized to be the Prophet Muhammad, Kaiser Wilhelm, Adolf Hitler, etc.) But the most commonly held opinion among scholars and theologians is that it indicates the Emperor Nero — whose name and title in gematria, which assigns a numerical value to each Hebrew letter, add up to 666. John of Patmos, a direct witness to the brutality of the Roman war against the Jews in 66 AD, would have had reason to point his wrath at the God-emperor of Rome — and equal reason, for fear of political reprisals, to bury that wrath under a layer of code.

Ancient Roman coins depicting emperor Nero

Of course, if you buy that 666 means Nero, that means John of Patmos’ prophecies refer to events that have already happened. That’s antithetical to the stance of Christian futurists, who are on constant tenterhooks for the apocalypse. Much of the premillenarian dispensationalist worldview, which originated in nineteenth-century upstate New York, hinges on elaborate extrapolations from individual verses across both Testaments, with Daniel and 1 Thessalonians particularly favored — and atextual, multi-millennium gaps inserted at convenient points in prophecy. It’s an obsession with the end-times that sees Armageddon everywhere, undergirding contemporary politics, which are perpetually teetering on the edge of a time of great persecution for Christians.

Like Taylor Rousseau, American evangelicals have an almost fetishistic view of this persecution, which they spend an inordinate amount of time preparing for. The notion that Christianity will soon be outlawed on pain of death is omnipresent in certain theological circles. Online, you can find youth ministries peddling ideas for “Persecution Games” to play with Christian campers: adults portray secret police who capture and torture Christians (“The jailer can ‘torture’ them as much as you want, have the jailer dress up and look scary, make a scary jail, use black lights, whatever you want… ”); adult “Communists” seek to capture Christian children and steal their Bibles. It’s in the context of this roiling persecution complex that a fantasy of being beaten to death for refusal to take a vaccine begins to make sense.

Mark of the beast scares go back a long way; as the medievalist professor Richard Landes told Wired back in 2006, Johannes Gutenberg’s moveable type was initially taken as such a mark. The notion is intertwined with commerce — without the mark, you cannot buy or sell — so over the last century, changes to American commercial systems have created paroxysms of evangelical anxiety. These cyclical panics can be roughly grouped into two types: the first concerns economic collectivism and the specter of godless Communism and socialism, a fusion of Scriptural and political preoccupations. The second concerns new commercial technologies; these waves of dread serve as a pressure valve to ease anxiety about technical evolution and change. (Speaking of which: yes, there are plenty of people who believe that bitcoin is the mark of the beast.)

Perhaps the most clearly political of these panics boiled over around Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Fundamentalist opposition to F.D.R. was widespread, as it was believed that he was intimately allied with the atheistic forces of world Communism; his social-welfare policies, in the words of the scholar Matthew Sutton, were “subverting God’s order and assuming responsibilities that God had assigned to churches and local communities.” One significant economic development of the New Deal was the National Recovery Administration (the NRA, but not the one you’re thinking of), designed to stabilize the supply and pricing of manufactured goods while offering workers an opportunity to organize. Its symbol was a blue eagle — widely interpreted among fundamentalists as a mark of the beast. FDR was considered by many in evangelical circles to be a forerunner of the Antichrist, if not the figure himself.

The beastly logo of the National Recovery Administration.

Another of Roosevelt’s initiatives that attracted an intense and lasting apocalyptic penumbra was the Social Security Number, introduced in 1936. Because, over the years, SSNs have become indispensable for many jobs (without it you cannot buy or sell — or get a W-9!), fundamentalists have long raged against the concept, expressed in periodic lawsuits. Most recently, on June 28 of this year, 2021, the Supreme Court declined to address a five-year quest by an Idaho man named George Ricks to obtain an exemption from providing his SSN.

“By forcing me to disclose an SSN in order for one to buy my labor or for me to sell my labor, is in essence the number of the beast and the card is a form of the mark," Ricks wrote in his filing before the court, to no avail.

In the fascinating book American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism, Matthew Sutton depicts fundamentalist figureheads as defending against the “satanic forces [of] communism and secularism, family breakdown and government encroachment” besieging the United States — of which the New Deal, with its economic collectivism and support for workers’ rights, was at the vanguard.

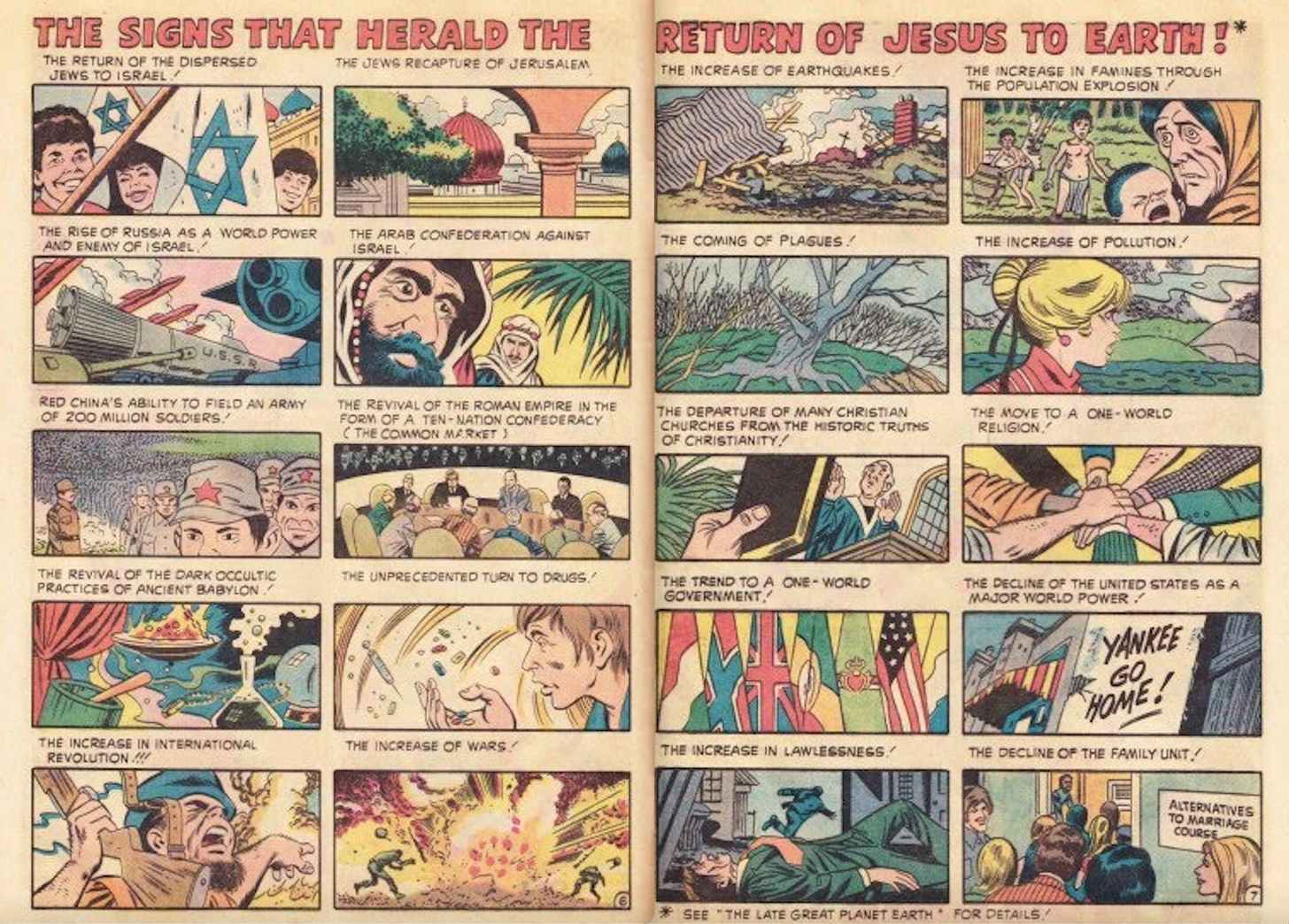

Apocalyptic thinking became a Christian cause célèbre in the 1970s, following the wild success of a book by premillennarian dispensationalist Hal Lindsey called The Late, Great Planet Earth. The book — an entreaty for the faithful to look to Christ in the imminent time of tribulation, heralded by, among other things, the European Common Market, drug use, “Communist subversion,” the establishment of the State of Israel, and “the alliance of the Arabs and the Russians,” and among other phenomena. Between 1970 and 1999, the book sold 35 million copies in 50 languages, warning direly of the “computerized society” that would enable “everyone who will not swear allegiance to the Dictator to be put to death or to be in a situation where they cannot buy or sell or hold a job.”

A comic book version of Hal Lindsey’s “There’s a New World Coming”

Following directly on Lindsey’s apocalyptic vision (elaborated on in such sequels as 1972’s Satan is Alive and Well on Planet Earth, 1983’s The Rapture: Truth or Consequences, and 1984’s There’s a New World Coming: An In-Depth Analysis of the Book of Revelation), End Times panics began to cluster around burgeoning commercial technologies. Bar codes for scanning products with greater ease were introduced in the U.S. in the mid-1970s — and ran immediately into rising apocalyptic fervor. Protests at grocery stores surfaced; an urban legend spread that the number of the beast, 666, was embedded in the lines of the code. One of the IBM engineers who invented bar codes, also known as UPC (Universal Product Code), received an anonymous letter purporting to be from Satan himself, thanking the man for carrying out his wishes so precisely.

It didn’t stop in the ‘70s — or with bar codes. In 1984, Pat Robertson averred that credit cards were a precursor to widespread mark-of-the-beast hand-and-forehead microchipping, which became a surprisingly durable source of Revelation woes for the next few decades. RFID (Radio Frequency ID) chips — which gained popularity in the early 2000s as a more durable and convenient form of identification than the bar code — sparked a surge of millenarian angst, particularly in 2004, when the FDA approved a chip that could be embedded in human skin called the VeriChip. One devout author wrote a book entitled The Spychips Threat: Why Christians Should Resist RFID and Electronic Surveillance, calling the new tech “uncannily similar to the prophesies of Revelation.” The prediction that microchips will migrate from credit cards and smartphones into hands and foreheads has thus far not manifested itself in any widespread fashion. But it’s directly from these panics that the dual hypotheses underpinning Christian anti-vaxx sentiment arise: that the vaccine is full of secret microchips, and that it’s the mark of the beast.

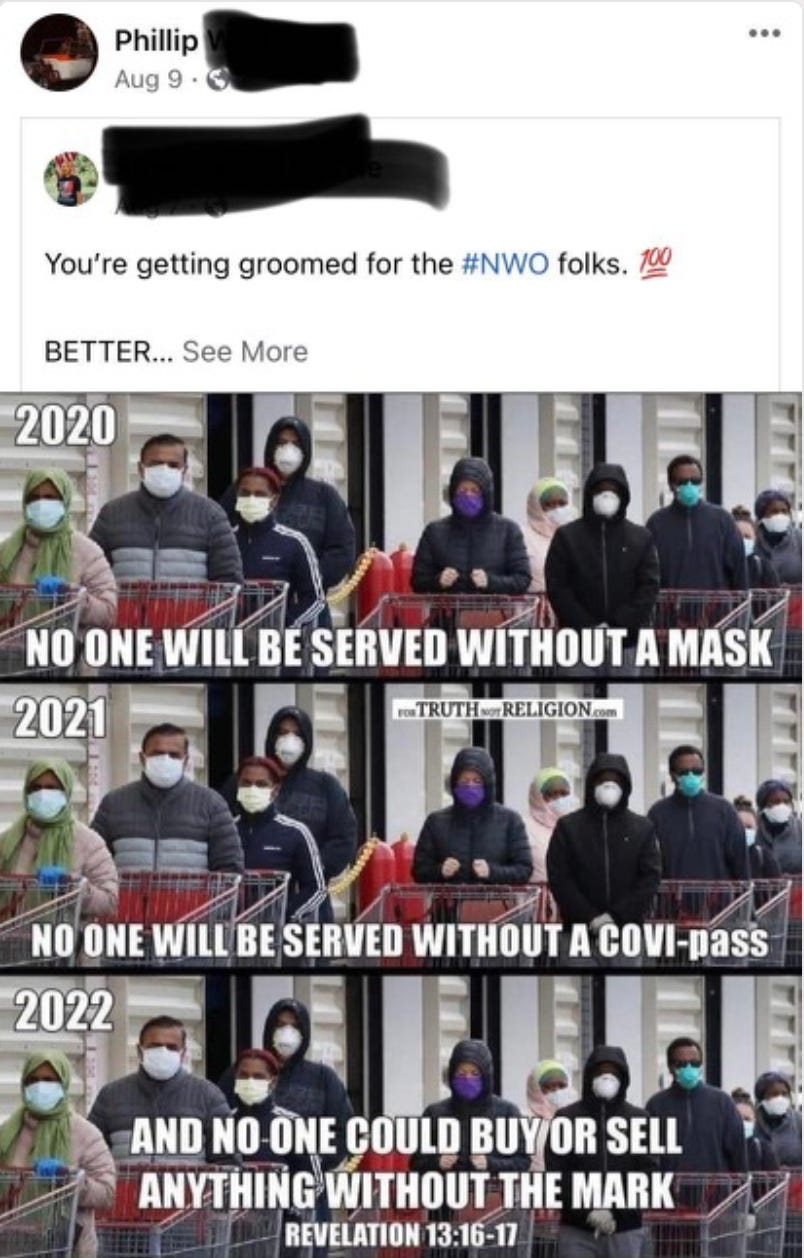

A Facebook post from earlier this year

Anxieties about the mark and what it heralds — Tribulation, Rapture, the enemies of Christ consigned forever to a flaming abyss — were and are commingled with a certain eager anticipation. “I think we have to recognize it as a hopeful sort of terror,” Anna Merlan, author of Republic of Lies: American Conspiracy Theorists and their Surprising Rise to Power, tells me. “If you’re a millenarian or not, the folks who believe in the mark of the beast also want to see it appear, since it marks the beginning of the period of time that ends with the Second Coming. That’s why there have been so many false starts. It’s a hope that their suffering — for example, being asked to get vaccinated — will be rewarded.”

In some sense, this latest panic is the culmination of a century of anguished, ecstatic anticipation of the end. It’s a synthesis of both strains of anxiety that have led to prior outbreaks of this specific dread: the fear of collectivism and government overreach, and the fear of new technology. Vaccination, after all, is a fundamentally collective endeavor: while it is protective of individuals, it works best when employed en masse. Moreover, vaccine mandates are a top-down proposition (they dictate what jobs you can have in certain sectors, and, therefore, without too much contortion, what you can buy and sell). The faithful who object echo the Christian Cold Warriors of the past, with their fears of totalitarian excess.

As the apotheosis of an era of fear, of technology and of the government, it makes sense that this particular panic should be the deadliest of them all. It’s one thing to protest bar codes at grocery stores, or refuse to use a credit card, or even to reject a Social Security Number; it’s another to suffer, over long and agonizing weeks, in the sterile confines of a hospital room, as your lungs turn stiff as glass, until you drown on dry land.

Many former evangelicals have written about the terror that the Rapture instilled in them as children — the expectation that any day now, they or their parents would vanish into the arms of Jesus, never to return. This fear was intimate and present, a catch in the throat at opening the door and wondering if your loved ones would be there or gone forever. The nation’s death toll has topped 700,000 despite the widespread availability of vaccines, with recent deaths concentrated in the disproportionately unvaccinated, highly religious Southeastern states. Evangelical Christian faith, and belief in the imminent apocalypse, is only one part of a complex matrix of anti-vaccine sentiment, albeit one with a rich and complex heritage of dire warnings. The notion of martyrdom can be thrilling — thrilling enough to dramatize and act out on TikTok over and over again, for one — but it also means you have to die first. Too many people, led by the fickle forces of prophecy and belief, are doing just that.

This is a great starting essay! Historical interpretation of torah and bible passages fascinates me, so, for my sake, feel free to dive in deeper to the 'mark of the beast' and Revelations and all associated history.

Also always shaking my head that the people who believe this stuff think they are "suffering" by being asked to do something mildly inconvenient.

Holy wow. This is probably the most well-written and in-depth essay I have ever seen on this topic. I was vaguely aware of some of this, but I had no idea how far spread and pervasive this issue has been in the Christian community. The only thing about this that disappointed me was myself when I clicked play on maybe the worst youtube video ever created,