Welcome back to Culture Club, a feature where David and I write about what we’ve been reading, watching, playing, and listening to, for paid subscribers. Please enjoy this free preview, and consider upgrading to support two struggling journalists at once! — Talia

2023 has been a banner year in the history of the scam, thanks mostly to George Santos, the man who put the “con” in Congress. Last week, Santos became only the sixth member of the House of Representatives to be expelled—but don’t mistake that for an act of atonement on the part of the Republican party. After all, the GOP’s all-but-anointed nominee for next year’s presidential election is the biggest grifter in American history. Like lots of con artists, Trump convinced countless unsuspecting marks that he was a good businessman; he was actually a historically bad businessman, but he told the lie loudly and long enough that it didn’t matter.

“Trump is, to his core, a con man. And a con man can pick out a mark from a mile away,” writer Tim Alberta told David Axelrod this week. “He saw easy marks (in the evangelical community) and he got them to go along with his latest grift. And it's proven to be fabulously successful for him.” As P.T. Barnum famously said, “there’s a sucker born every minute,” and if enough of those suckers make it to the ballot box next fall, we will all have been played, for the second time in a decade.

As you’ll see, con artists come in all shapes an sizes, from two-bit hustlers to Ponzi schemers to pseudo-aristocratic imposters. In Genesis 27, Jacob posed as Esau to steal their father’s blessing. In the pursuit of potential romantic conquests, Zeus posed as a swan, a bull, and a cuckoo. Inspired by this august legacy and our particular moment of rampant chicanery, I decided to do a deep dive and learn a bit about some of the most notorious con artists in history.

From the False Dimitri and “Lord Gordon Gordon” to Bernie Madoff, Anna “Delvey”, and “Dirty John”, these are figures one should not, under any circumstances, take into your confidence. Consider this collection of archival stories an instruction manual into the art of the con—and your first line of defense if you ever encounter George Santos in the wild.

Who Was Deceiving Whom?

By Jonathan Sumption

New York Review of Books, June 11, 2009

In a world that finds the present odious and longs for the appearance of a savior, impostors offer legitimacy and salvation. It is a heady combination.

The classic case is the pseudo-Dmitri, the monastic oblate who passed himself off as the son of Tsar Ivan IV of Russia at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Dmitri was the only impostor in European history to make his pretensions a reality. He actually succeeded in occupying Moscow and mounting the throne for a period of ten months. But he was typical in every other respect. He achieved what he did by exploiting the political divisions of Russia and recruiting support among the country’s foreign enemies. The reigning tsar, Boris Godunov, was widely believed to have usurped the throne by murdering the real Dmitri. His government had been undermined by three years of civil war, harvest failure, famine, and signs of divine disapproval. Although backed by an army consisting mainly of Polish mercenaries, Dmitri was able to make use of the strong apocalyptic streak in Russian opinion and present himself as a savior.

Arrest of the Confidence Man

New York Herald, 1849

For the last few months a man has been traveling about the city, known as the “Confidence Man,” that is, he would go up to a perfect stranger in the street, and being a man of genteel appearance, would easily command an interview. Upon this interview he would say after some little conversation, “have you confidence in me to trust me with your watch until to-morrow;” the stranger at this novel request, supposing him to be some old acquaintance not at that moment recollected, allows him to take the watch, thus placing “confidence” in the honesty of the stranger, who walks off laughing and the other supposing it to be a joke allows him so to do. In this way many have been duped, and the last that we recollect was a Mr. Thomas McDonald, of No. 276 Madison street, who, on the 12th of May last, was met by this “Confidence Man” in William Street, who, in the manner as above described, took from him a gold lever watch valued at $110; and yesterday, singularly enough, Mr. McDonald was passing along Liberty street, when who should he meet but the “Confidence Man” who had stolen his watch…On the prisoner being taken before Justice McGrath, he was recognized as an old offender by the name of Wm. Thompson, and is said to be a graduate of the college at Sing Sing.

”Lord” Gordon Gordon—the Career of a Pseudo Nobleman.

The New York Times, August 5, 1874

He was the son of moderately well-to-do parents, who, when he was a mere lad, resided on the borders of Scotland. When engaged in study with his brothers he had been in the habit of frequently expressing a desire to be wealthy and noble. As years went by he seemed to become more and more settled in his determination to cut a lordly figure in the world or die in the effort to obtain the means to enable him to do so. When he was old enough to begin the world for himself the position of clerk in a commercial house was procured for him. The position, however, was not to his taste. The possession of money in small sums made him long to have more, and he finally gave up his situation in order to find readier means of accomplishing his purpose. After that, little was heard of him by those who had known him in his boyhood. It is supposed that, having decided to play the role of a Lord, he contrived to secure the acquaintance of a real one, in order to study his part carefully. He wore expensive clothes, handsome jewelry, and soon succeeded in inducing all he came in contact with to believe that he was a man of wealth. In England, persons who are termed confidence swindlers in this country, very often worm their way into the books of the tradesmen through the agency of clergymen. Gordon made a very liberal use of this plan.

The Confidence Man

By David Samuels

The New Yorker, April 18, 1999

In the first weeks of March, 1872, it seemed, Jay Gould and Horace Greeley, two of the best-known and most powerful men in America, had used all their resources to wheedle, bribe, and flatter a man whose account of himself should have been dismissed, by any reasonable person, as a colorful bouquet of lies.

As abruptly as he had appeared in New York, the child of his own imagination, Lord Gordon vanished from the historical record. He survives today mainly in scattered footnotes and in the imaginations of a composer and a librettist in Canada, who in the nineteen-sixties conceived an opera—never completed—about Lord Gordon's last days. The opera was based on materials that are now in the Provincial Archives of Manitoba. There I found several folders and documents that led me to the archives of the Northern Pacific Railroad at the Minnesota Historical Society, to the files of the New York State Supreme Court, and to period newspapers and! other places where fragments of Lord Gordon's life have been preserved. What emerges from these records is more than an outlandish mosaic of fraud fashioned by one of the most gifted con artists in American history. It is also a dramatic parable of the Gilded Age, of the deceptions of its leading men, and of the great American myth that survived them.

The Lure of Easy Money

The Idaho Statesman,, June 13 , 1915

A “grande Thérêse!”

Thus the Parisians dubbed Mme. Frederic Humbert, who on the strength of a fletitious fortune of $20,000,000, supposed to be concealed in a great safe in her bed-room, borrowed right and left from great bankers and obscure individuals money that enabled her to live in magnificent style and play a prominent part in the social life of Paris.

Litigation was the Instrument by means of which Mme. Humbert's credit was maintained and the exposure of her fraud deferred. For more than a score of years this woman maintained that there existed two brothers, Robert and Henry Crawford, whose suits and counter suits prevented the opening of the safe, the vacuity of which weld have at once balked la grande Thérêse in her ambitious projects and consigned her to deserved punishment.

Ponzi Won’t Reveal Method at Present

Boston Globe, August 1, 1920

Charles Ponzi, proprietor of the Securities Exchange Company at 27 School St., will never divulge his methods of "getting rich quick." Yesterday afternoon, in reply to a query as to his future plans, he declared that he had absolutely no apprehension as to the outcome of the audit of his books and papers, and that while he was anxious to lend his cooperation to Edwin L. Pride, the auditor appointed by United States Dist Atty Gallagher, it was only to the extent of determining his own solvency.

Mr. Pride had previously stated that he was not prepared to make any statement upon the case. He explained that he and his corps of experts had been at work on Ponzi's books and card index system 24 hours, and that they had merely “scratched the surface.”

“I shall never make public my methods of doing business.” declared Ponzi. “By that I mean that for the present I shall continue to maintain my secret; sometime I may tell how I did business, but it would he manifestly unfair to persons who have been associated with me to divulge the methods at present.”

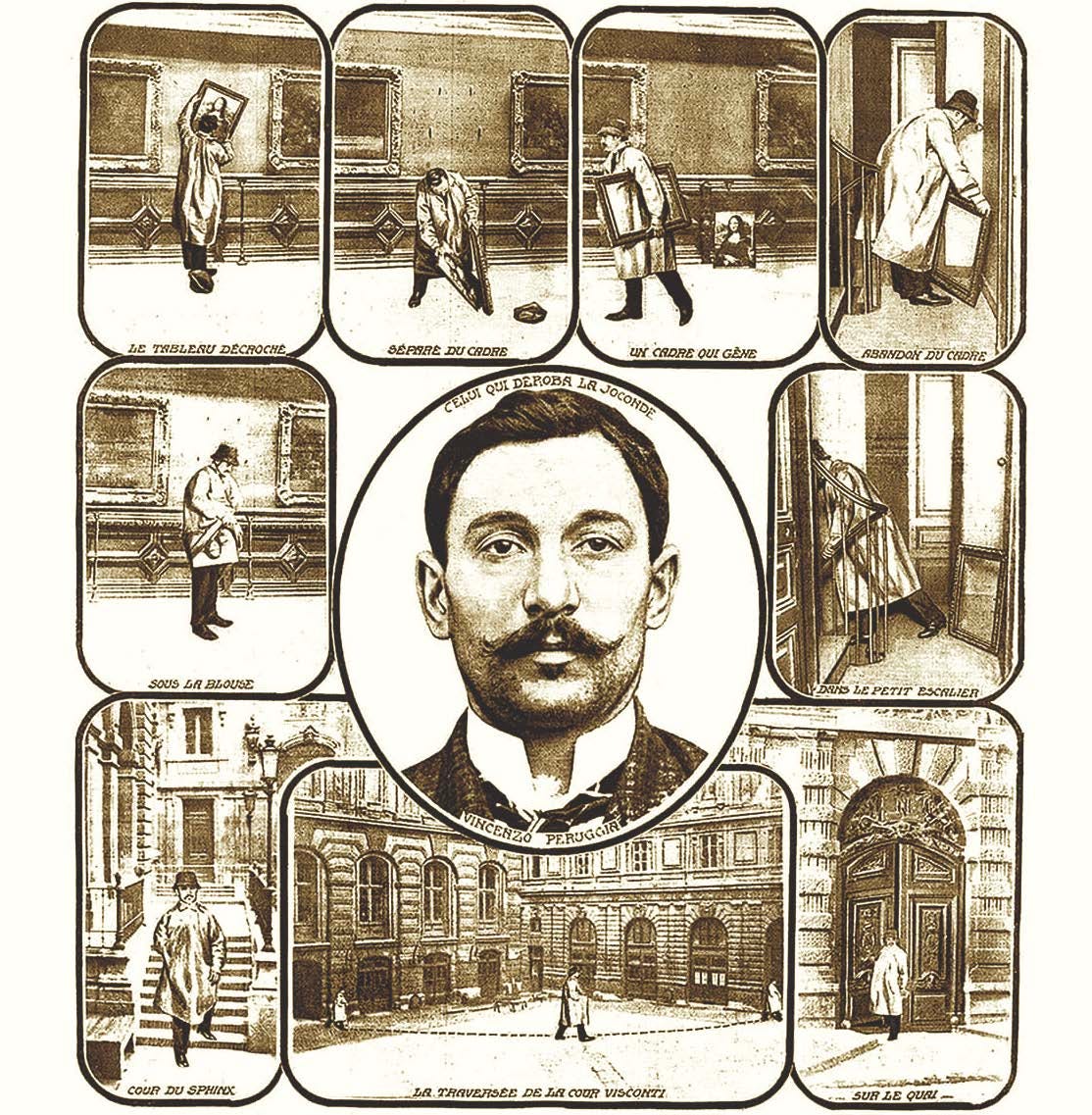

Why and How the Mona Lisa Was Stolen

By Karl Decker

Saturday Evening Post, June 25, 1932

For twenty-one years the story of the world's greatest single theft has been kept “under the smother.” Until now there has been not even a hint of the tangled and intricate plot of which it was the mainspring.

Da Vinci's Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre on August 21, 1911. The picture was valued at $5,000,000 in itself. Just how many millions it put into the pockets of the clever thieves who took it never will be known. It made them all rich enough to retire. But, you protest, the picture was recovered two years later, still in the hands of the thief, who, instead of profiting, went to jail for three years.

That, of course, is the story of record. The picture was recovered, the actual thief went to prison and the French were content to get La Joconde back in her old place on the wall of the Salon Carr without investigating too deeply. Back, however, of this record of futile, foolish theft lies the true story, a tale of underworld high finance known only to those who were concerned in it, and to the writer, to whom it was told with the understanding that it was not to be divulged until permission was given or until the narrator had died.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sword and the Sandwich to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.