Hope and Woe and Roe v. Wade

To hope in this world is an unreasonable thing to do, and that is why I do it

Edited by David Swanson

I find myself unable to stop planting things.

Most of the seeds I’ve sown haven’t germinated, at least not yet; the scallions, cucumbers, tomatoes and two different kinds of beans fell victim to both my inexperience and a period of unseasonable cold. Still: there are radish seedlings putting out tiny plate-shaped leaves, and lavender seedlings swelling daily, and leggy little stalks of dill filling a planter end-to-end, to someday perfume the air and supplement my table; today in the sun I sowed chives and parsley, in narrow new boxes that smell like cedar. It’s the first spring in the first year in the first backyard of my adult life, the first time I’ve ever planted a garden. Most of the seeds may never grow, and some of the seedlings may fall prey to high wind or the neighborhood’s ever-curious stray cats—but some do take root, and every day I watch them, drinking light, growing. So I keep planting, in a kind of hopeful fever.

A garden as a metaphor for hope is one of the more shopworn tropes a writer can turn to, but at the moment it feels compulsive—like the urge to plant itself. Planting a seed in the earth (even if you’ve had to buy the earth in plastic sacks) and watering it carefully and waiting is inherently a hopeful act—it implies that you’ll be around to see the crop, that there will be a crop, that the sun, rain and other meteorological phenomena such as dew and shade that contribute to the whole enterprise will persist, that there will be no apocalypse just yet. Even if everything feels apocalypse-shaped, brimming with present disaster, and looming disaster as well.

My time chronicling the rise of the far right since 2017—and more to the point, watching it grow, and expand, and mutate, and draw ever closer to the throbbing center of American politics, like sclerosis in an aorta—has made the cultivation of hope something of a trial. That reality has, of course, registered more sharply than ever this week, with the news of the impending devastation of Roe v. Wade pervading every airwave and every waking moment. The movement that brought us to this moment has been carefully planning for half a century, engaging in deliberate, radical, cunning, sometimes murderous, and often underhanded actions in order to bring its theocratic, minoritarian vision into practice. The rights of women, queer people, trans people—and generally anyone not straight, white, male and Christian—feel precarious as hell right now, already being swept aside by a flood of legislative bile. The leaders of the party nominally in opposition to said theocratic minoritarian agenda are feckless, jelly-legged gerontocrats with the collective backbone of one filleted sprat, and seem capable only of asking for more money without proposing to do absolutely anything useful with it. The dumbest people in the world with the fanciest degrees are polysyllabically telling those whose bodies are about to be subject to the surveillance-enhanced violence of a police state to just calm down.

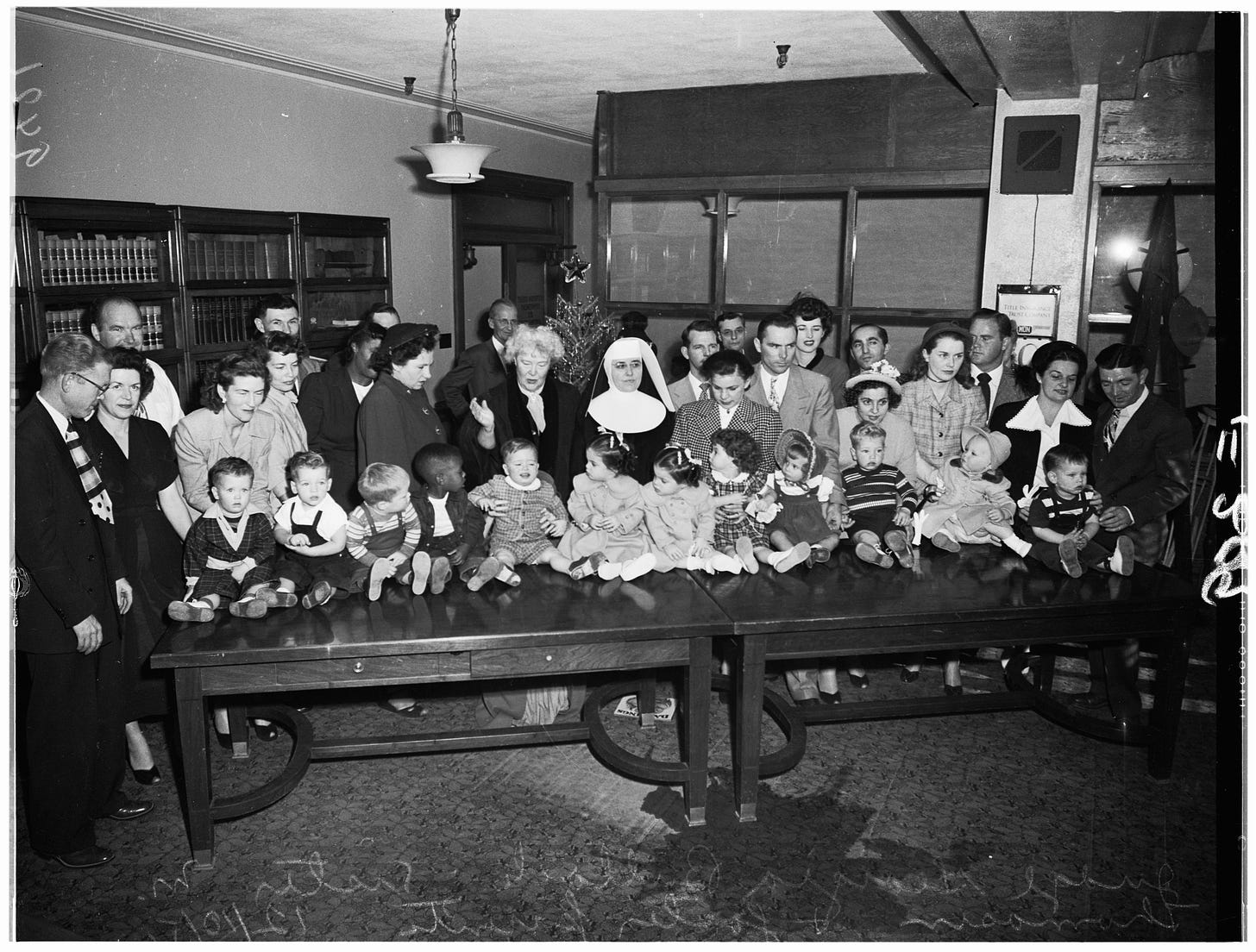

Perhaps the most dystopian aspect of all this is the way the dissolution of the Roe-era social order coincides with decades of growth in the evangelical Christian adoption movement, a swelling hybrid born of the social imperative to cultivate large families, and the desire to impose Christian salvation on any available human target. With wellsprings drying in the usual sources the Christian adoption movement has drawn on in recent decades—Haiti, Liberia, Ukraine—the scrutiny has turned inward, to what Justice Alito called in his draft opinion overturning Roe “the domestic supply of infants.”

Those who want to wind the social clock relentlessly backwards seem to be fixating on a particular period of American history—the years between 1945 and 1973, known to social historians as the “Baby Scoop” era. During that time, some 1.5 million pregnant girls and women were sent away to maternity homes to deliver children out of wedlock, gave birth in often abominable conditions, and were coerced, in many cases, to sign away their maternal rights before even coming to full consciousness after the “twilight sleep” of labor. “Those who wanted to keep their babies were threatened with financial penalties, since many homes only covered the cost of prenatal care and room and board if the child was surrendered,” wrote the author Kelly O’Connor McNees, in a Time article drawing parallels between the Baby Scoop era and Texas’ 2019 restrictive abortion law. “Some women who refused to give up their babies were committed to mental institutions.”

Then, as now, eager would-be adoptive parents frequently cared little for the often terrible grief of the birth mother, preferring to stifle the concerns of female agency, bodily autonomy, and severe financial stress under a shroud of silence. As Kathryn Joyce chronicled in her searing look at the fundamentalist adoption industry, The Child Catchers, many evangelical adoptions fail because of the gulf between ideological zeal about widening the fold of Christianity and the actualities of raising children that come from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, have disabilities, or are of a different race from their adoptive parents. (That evangelical parents, as has been chronicled here before, tend to raise their children in environments of often extreme physical and psychological abuse simply adds another layer to the horror of the situation.) Expanding the domestic supply of infants by force is an act of violence that will beget, as the Baby Scoop era did, generations of grief.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Knowing all this—and knowing more, all the factoids about the way far-right sentiments often begin in molten misogyny, about the thirst for female subjugation, the desire to “undo the Sexual Revolution” and take away the Pill and render everyone with a uterus a vessel for breeding (white babies, in particular) that are endemic to nearly every group within the broad and fractious collective that is the American right bouncing around my skull every hour of the day—it is very difficult to find hope and more difficult still to remember to seek it.

But I’ve spent this past week raising money for the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund—largely, it must be said, by making comical videos involving me, in my new backyard, chopping up increasingly implausible foods with swords. The MRFF is an organization with its boots firmly on the ground, whose activities, day by day, look humble: a diaper pantry, a Little Free Library, the booking of hotel rooms and offering of assistance to abortion access for those who need it. I chose a local fund from the National Network of Abortion Funds’ list because better-known groups like Planned Parenthood and NARAL have war chests, and because their broader messaging has often fallen short. I chose Mississippi because that’s the state that brought the suit the Supreme Court is using to kill off abortion rights for good. And because the people who are facilitating abortion access in Mississippi know a thing or two about battling against impossible odds, about not losing hope, about continuing a fight so many millions long abandoned and turned away from.

We raised $32,000 in a few days, which is, of course, a tiny drop in the very large bucket of need that is only going to grow and grow as this darker era dawns. Still, it will cover a few hotel stays, a few procedures, perhaps a few diapers—in a place in desperate need, a place that people have given up on, or still worse, want to consign to the trash heap along with all its inhabitants. What was true yesterday is true today and will be true even after the Supreme Court overturns Roe: every person who needs an abortion in Mississippi deserves access to one. And the same is true across the nation and the world. Turning to those who have been working for years to provide those rights in the face of intractable, zealous and violent opposition makes sense: they can be our guides through the temptation to shy away in despair.

And so the whole ridiculous fundraising campaign felt not unlike pressing a tiny black chive seed into the earth and hoping for the appearance of an allium. It’s an act of defiance and an act of hope—hoping that with precisely enough sun and water a piece of green will rise up over the concrete and curl toward heaven. There are those who would tell us to passively, calmly await the evisceration of our rights, to slip into a twilight sleep of numb despair, to shut up and listen to the bureaucrats with liver-spotted hands and their mewling irrelevancies, to politely live in the quiet hellscapes the foot-soldiers of God love to create. There are those who pule about civility because it is more polite to die than to object to the circumstances that will lead to your death.

They are not worth listening to. To seek hope is an action, not a simple or benign or gentle one, not a bromide, not an easeful path: it means doing what you can, and refusing not to. It means getting your hands wet and dirty and caring about things and tuning out the reactionary voices that purport to be the narrators of reason. To hope in such a world is an unreasonable thing to do, and that is why I do it; reasonableness would be a terrible thing to contract at my advanced age. I hope I never do.