Hope is a Discipline

On the spring equinox & the physical consequences of a roiling inner world

Yesterday was a lot of things: the twentieth anniversary of America’s invasion of Iraq; another day in the bans on drag performance, trans healthcare, and abortion rights traveling their sadistic upwards routes through state legislatures; another school shooting, this one in Texas, with a single-digit body count, too scanty to make national news; racist cops appearing before a grand jury after killing a black man; and so on. Insert between the semicolons, if you will, any number of disasters—both immediate and incremental, both natural and manmade—and the infinitesimal shortening of all of our lives thereby.

It was also, and I say this aware of every pained clause in the preceding sentence, the first day of spring. On the vernal equinox, day and night are of precisely equal duration: a moment of precious, precarious balance. And I turned up my face to the sun and the wind was warm.

In this job, I write about a lot of things that weigh me down; if and when I find a gray hair sprouting from my rotten melon of a head, I will probably owe it to, among other things, the come-to-Jesus memoir I’m reading by a Christian extremist, and all that work I’ve done to pry into the psyches of those like him. This week I’m writing about anti-trans laws for a national magazine and while I am so, so excited to get work, I must admit it is a stone cold goddamn bummer. I feel it in my stomach, where a lot of my anxiety resides, and a throat that feels clogged and itchy with strain.

Over this long winter I have run smack into despair on a number of occasions—Wile E. Coyote-like collisions into brick—and lain splayed and prone and longing to pause, if not stop for good. But always I snap the cricks from my joints and lumber back into some sort of motion, even if the air feels cold and thixotropic. I am, I know, quite ill—agoraphobia is no joke in a pandemic-era New York winter—and for the past six months my mind has malfunctioned like a radio dropped out a third-story window. I keep squawking even as I hit cement, though. Tinny voice, smashed speakers, frayed wires. I keep going.

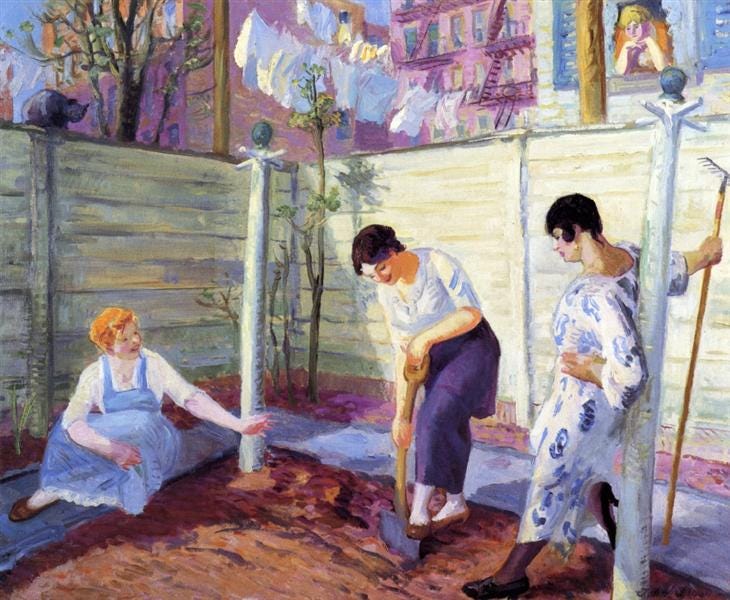

It was warm for a few days two weeks ago, and I planted seeds. Cold-hardy plants, determined by careful perusal of the USDA Zone 6 Guidelines in my book on growing vegetables in New York: seed potatoes; onion sets, which are cocktail-onion-sized little buds; spiky beet seeds, pressed lightly into black sphagnum-enriched soil, in rows.

The first real snow of the season came a few days later—skirling down, not sticking, just soaking the newly-turned soil with cold—and I fretted but kept waiting for germination. I’m waiting, still.

It’s paradoxical that most of the time I feel so suffused with despair you could wring it out of me, but all the things I do rely upon hope. Writing involves a great deal of hope: that I can muster up the wit to articulate an idea and the discipline to write it down; and the far more audacious notion that, having done so, I can shepherd it to a willing audience eager to consume my words.

That’s a tough enough notion with a newsletter, but far more so when it comes to writing a book: I am betting—with a gambler’s perennial and necessary hope—that two years from now you will still want to read what I write. That I’ll have managed to pull off the high-wire act of writing something timely but enduring. Hell, that I’ll still be alive! And that the various companies involved will deliver, and a physical paper object with my name on it will emerge from all those hours of pained research and teeth-sucking and pacing and writing (and shaving-down and fine-tuning and multiple legal reviews).

Just because I’ve done it once before doesn’t mean it’s any easier this time. It isn’t. It’s worse, somehow, the way sophomore efforts still bear the weight of all the dreams you ever had, and all the expectations of your first sally, and your own expectations of growth and maturation. And still, I sit down, and I write. I research. I close my eyes and cross my fingers and do the work.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

When you run headfirst into despair the abrasions and bruises appear in unexpected places. When you’re isolated and vulnerable and overburdened you tend to do dumb things, in an effort to externalize your woe, make it real: spend money unwisely, say; indulge in substances. I used to take the notion very literally and burn my skin with matches and cigarettes; that is one of the only bad habits I’ve ditched, and it took more than a decade. Sadness writhing inside you is so inchoate.

The desire to give up, the dearth of hope when hope is what you need in order to perform any of the duties you must, and attain any of the joys you so dearly want—the empty inner tank, the last drops of fuel burned up, the certain knowledge that you’ll never get better and nothing ever will—no one else can see that. Or decode it. No one can read it in your eyes; eyes aren’t really like that—they don’t have I’M NOTHING written on them in sans serif type. Red wine on your teeth, black-tar stains on your fingers, a bank account you’re afraid to look in the eye, these are concrete things. It’s so much easier to point at an irresponsible debt, or a taut swollen burn, and say, look, here’s the problem.

The converse, though, is that you can physically manifest hope, too.

Those seed potatoes, the onion sets, they haven’t sprouted yet. But last year’s sage survived against all odds, and when you pinch it between your fingers it smells perfect; when you hold it up to the sun you can see every vein in the leaf, through which all that’s green and growing flows. The woody stem bobbed and then held. The succulent that grew so big it overhung the pot shrunk to a little nub—but the nub held, even as the limbs fell away. It looks like a gem lettuce, that thick cup of green, sturdier than winter.

I have an urn full of seeds to plant—I bought out half the Burpee catalog, or anything that said partial shade or cold hardy or thrives in low sunlight at any rate. I signed a two-year lease. I watched the person I love most in the world say yes to a big new step. I gritted my teeth and made an appointment that scared me, figured out a tax plan, wrote this column, will write another. Time after time I have made myself numb and made myself move. When you come out of the cold you awake from numbness with pain, and then it passes. You’re swollen with chill, and then you warm, and your grasp gets firm again.

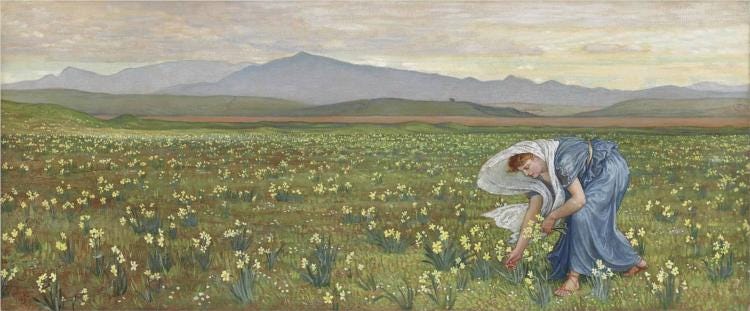

Yesterday I ran a mile, schlepping my body around the track until somewhere along the way I stopped plodding in my worn shoes, with my bad knees, the tattoo of an onion on my thigh nude to the breeze—I stopped plodding and flew a little. The sun stooped and kissed me. The wind was warmer today than it was yesterday, and tomorrow it will be warmer still. Tomorrow—the second full day of spring, after the equinox, when the world has tipped towards more light, I’m due to plant leafy greens. Kale, chard, spinach: dense verdant things that will be pale and then full. Whole things the rain will soak until they unfurl from the seed. Each one a little bit of a miracle. And as much as or more than a self-inflicted burn, those little leaves are a physical externalization of an inner world, only the inverse: they are proof I think I will be around to haul gallons of water up and down to tend them; that spring will come in its fullness and roll into the humid gales of summer; that the soil will shelter them.

A woman I loved taught me how to garden, and she died last summer, and I will sow a sackful of wildflowers, a handful in every planter I own, just for her. Every one that opens—aster and milkweed, coneflower and coreopsis, bergamot, primrose, blue flax—is an invitation to winged creatures. An assurance to self and others they will come. No one ever said hope was easy: it’s hauling four gallons of water up and down a flight of stairs day after day, making yourself continually face sluicing waves of terror, confiding a problem before it can fester too long in the dark, loving someone so much they could crush you. It’s trusting in you, reader, hoping you’ll get to the end of this column.

It’s spring; it’s perching yourself at the perfect cusp between day and night, and turning your face to the light, knowing its new abundance is going to spill into your life, into your cupped hands.

yes, I will read your book. your words move me deeply.

I will read your book. ♥