In Praise of Righteous Vengeance

On the Book of Esther, retributive violence, and the recurrence of those who seek to destroy those who won’t obey them

Today is Purim, a Jewish holiday that you’re either intimately familiar with or know nothing about. Few people are in between on this. To the outside observer, it’s one of the more obscure Jewish holidays, possibly even a made-up sounding one, like Shmini Atzeret or Hoshana Rabba (both real—they’re in the fall—and on Hoshana Rabba you ritually whip the ground with myrtle leaves while calling out prayers of praise. It’s pretty fun).

To observant Jews, Purim a tentpole holiday: it involves dressing up in costumes (that part is mostly for kids) and getting absolutely astronomically wasted (on this night the streets of Crown Heights run with vomit). Other traditions include giving to the poor, reading the Book of Esther with its own peculiar cantillation, and eating triangular cookies filled with jam. As far as my own experiences of the Jewish calendar go, I can take or leave the festivities around Purim—too much liquor is bad for my aging constitution, I can’t readily source a full suit of Spanish-forged armor for my preferred costume, and the cookies are often chokingly dry. But as to the story behind it, and the primary moral, I fucking love it. It is a holiday about the necessity for vengeance, and violence as self-defense, and it holds up pretty well in these escalatingly shitty times.

Here’s the not-so-secret message of Purim, right there in the Book of Esther: if someone tries to kill you and those you love—if people with power are plotting to massacre you—it is your sacred obligation to fight back, and to take vengeance unto death. Yes, this story contains beauty contests, perfumed virgins, suggestive touching of scepters, an absolutely wine-riddled emperor, horse parades, and dream interpretation. But at its core, it is a story of attempted mass murder and its repercussions. As much as it is about anything, Purim is about public executions: there are thirteen lynchings in the text, and eleven of them are direct retribution for attempted genocide.

A quick primer on the Book of Esther: Emperor Ahasuerus of Persia is in the midst of an enormous and prolonged banquet. He summons his queen, Vashti, but she refuses to come display her beauty for him. Enraged, he follows a vizier’s advice to banish Vashti from her queendom, and holds a beauty contest among the nation’s comeliest virgins to replace her. Enter Esther, a humble Jewish orphan who has been raised by her cousin Mordechai; she is so beautiful she enchants everyone she encounters and eventually becomes Ahasuerus’ queen. (Romantic.)

Meanwhile, the king’s chief adviser, Haman, has ideas above even his own exalted station, and forces everyone to bow to him; among the crowd, only Mordechai refuses. Haman equates the refusal with an injury to his person, and vows to avenge it with indiscriminate slaughter. In his desire to eliminate Mordechai—but concluding that a simple tit-for-tat is beneath him—Haman resolves to kill every Jew in Persia. Forthwith, he sends letters commanding the people “to destroy, to slay, and to cause to perish, all Jews, both young and old, little children and women, in one day, even upon the thirteenth day of the twelfth month, which is the month Adar, and to take the spoil of them for a prey.” In the meantime, Haman also assembles a special gallows just for Mordechai.

Esther catches wind of this and, through a combination of feminine wiles, earnest entreaty, and her pious Jewish faith, convinces Ahasuerus to both revoke his genocidal decree, and oust the perfidious Haman. Unable to cancel his decree entirely, the emperor instead encourages his Jewish subjects to fight back, “to gather themselves together, and to stand for their life, to destroy, and to slay, and to cause to perish, all the forces of the people and province that would assault them, their little ones and women, and to take the spoil of them for a prey.” Haman is hanged on the very gallows he assembled for Mordechai, along with his ten sons. Thousands of would-be executioners are killed by the self-defending Jews, and the day becomes a Jewish holiday full of feasting and celebration ever after.

Vengeance is ours, along with an annual festival combining costumes, treats and drunkenness.

It’s telling that Haman determines to destroy not just Mordechai but his entire ethnic group because of Mordechai’s refusal to bow down. It is this disobedience that drives Haman to murderous wrath, the way Mordechai sticks out, won’t do as the others do, won’t join the kneeling crowd at the king’s gate in supplication. It is Mordechai’s visible difference that makes Haman seek his death, and those of all he loves.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

There’s been a lot of genocidal rhetoric in the news lately—waxy-skinned CPAC speakers and conservative talking heads with patchy beards discussing the need to “eliminate transgenderism” as part of a “total war.” It’s hard not to see the parallel, here, when it comes to murderous wrath in the face of nonconformity. Full of more than my usual measure of rage, it is not without a certain sense of textual parallelism and satisfaction that I look upon this short, curt tale of nooses. What is better than a story that ends with the plotter hanged high from his own gallows?

With a very purposeful addition of insult to injury, whenever the name of Haman is uttered during the traditional reading of the Book of Esther, the congregation lets loose with noisemakers to drown out and figuratively erase his existence. In prior centuries, traditions included breaking clay pots; exploding firecrackers; writing his name on pebbles and tossing them in streams. The vendetta has outlasted the Persian Empire by millennia; for as long as there are Jews, we know we’ll face a Haman who will condemn us for being “scattered abroad and dispersed among the peoples.”

For the crime of being a small, powerless, dispersed people with a distinct cultural and religious identity, we Jews have been condemned to slaughter time and time again, and for this reason we need to continually curse the name of those who plot our demise. On this day we give gifts, and remember the righteousness of our vengeance, when we slaughtered those who came to slaughter us. Even the triangular cookies are called hamantaschen—Haman’s ears. We devour him bodily, with jam.

I come from a culture of exegesis: in Hebrew, what’s called the p’shat, or the surface meaning of any text, is merely a point of departure. From there a ladder of text, meta-text, mysticism, semiotics, argument and exegesis that rises over the millennia to the present. Through the generations, each text carries a growing penumbra in many languages, a concatenation of all the minds that have considered it. It is daunting to carry in one’s heart the totality of all this surmise, but, standing on such a ladder, one can grow giddy at the vision it grants.

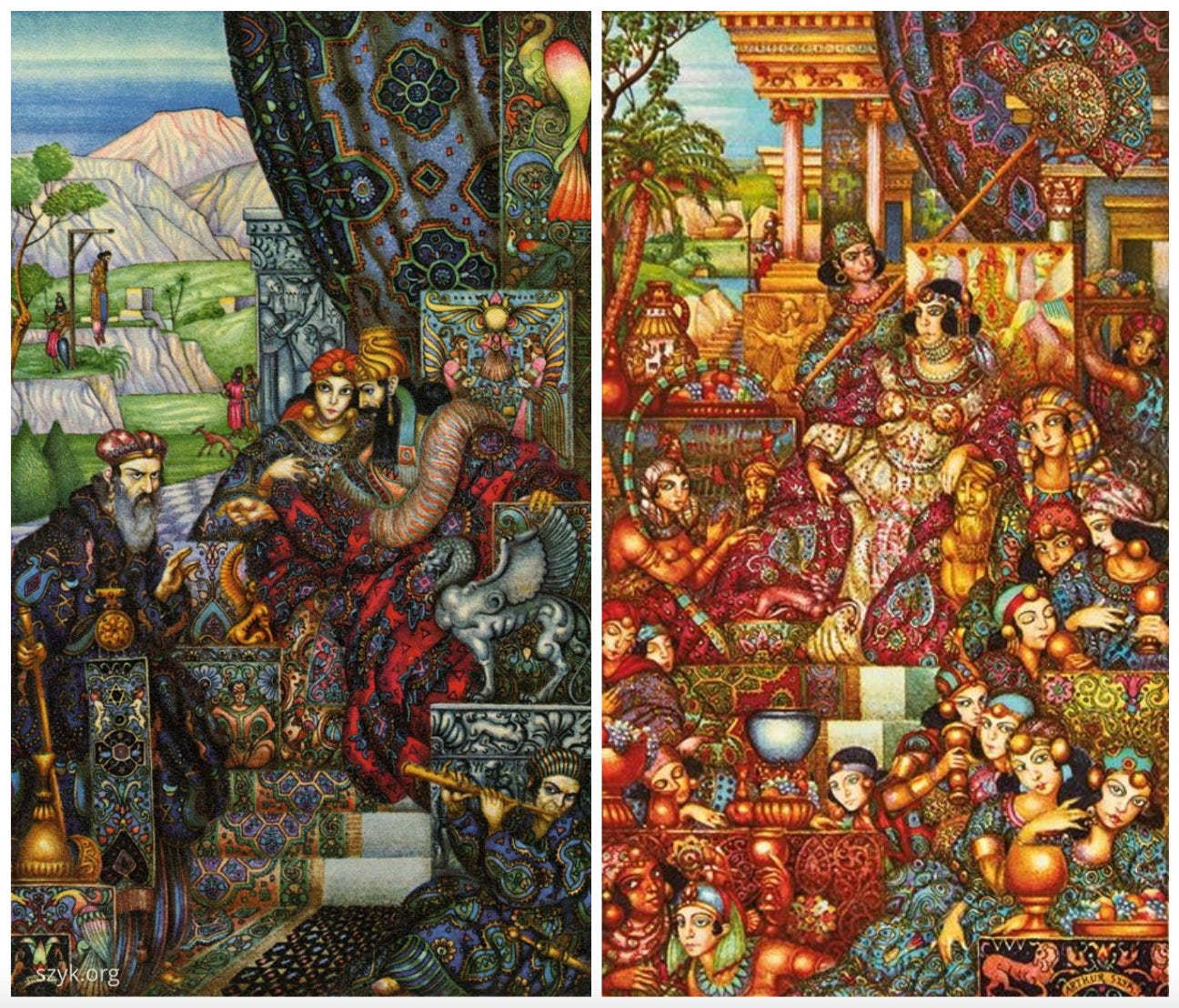

I think about this text—about the justice of retribution duly meted out; about the crime of plotting genocide, and its just desserts. I think about the way the Book of Esther has been used in antifascist contexts for generations, notably in the work of the Polish-Jewish artist Arthur Szyk, whose elaborate illustrations depict Haman hanged in full Nazi regalia. And I consider: what a gift it is to look at this book again as I have every year of my life, and think about how these ancient words redound in my time, when again the forces of cruel power seek to annihilate those who are abhorred because they will not obey.

Most of all I think about who qualifies as small and dispersed and different, whose self-conception is distinct and sets them apart. And how the evil sentiment that the powerless must be destroyed recurs as surely as the turning of the year. How in each era there is a vizier or a head of state or a religious figure or a demagogue who is always ready to call difference and dispersal a form of treachery and subversion. How should such a figure be met? How do we treat those who, in secret and in power, plot slaughter, and call publicly for the elimination of those who wound their boundless pride?

“And the Jews smote all their enemies with the stroke of the sword, and with slaughter and destruction, and did what they would unto them that hated them... The king commanded that Haman’s wicked device, which he had devised against the Jews, should return upon his own head, and that he and his sons should be hanged on the gallows.”

And the people said: Amen.

In the last few years I have come to believe that an important, fundamental political distinction, can be observed on how we see the act of killing another person in self defense: is it a righteous act or a forgivable transgression?

I believe the former attitude, in its most unhinged expression, is what ultimately leads to people with Punisher t-shirts carrying guns in the hopes of being provoked into an heroic act of self defense.

All of this to say, that I don't think violence can ever be righteous. Which is not to say don't be violent, just never forget the best it can ever be is the lesser evil.

Thank you for the lesson on the meaning of the Purim holiday and the story of Esther. As a person of Jewish heritage who did not grow up going to Temple or Hebrew School, I learned a lot. And while I am not really a violent person, I don't think I would have a problem defending those I love to keep them from being harmed for being "different," for not conforming to please or benefit others.