Ministry of Violence, Parts I—III

Corporal punishment, Evangelicals, and the Doctrine of Obedience

Edited by David Swanson

This post contains all three parts of the “Ministry of Violence” series, published throughout October and November 2021, in one place. The first section focuses on views of corporal punishment in evangelical culture, its historical background, the doctrine of demanding absolute obedience from children, and its effects. Part 2 is about the effects of childhood corporal punishment on romantic relationships, and Part 3 discusses breaking the cycle of abuse in parenting. The content of this series may be disturbing to many, as it will contain graphic descriptions of child abuse and its consequences.

A note on sources: Due to the delicate nature of these subjects, most of my correspondents asked to remain pseudonymous. Pseudonyms will be indicated by use of a first name; full names, unless otherwise indicated, are real.

In some hands, a wooden spoon is an innocuous object, a kitchen tool for stirring and scooping. In others, it is a weapon. “My mom wasn’t averse to carrying around a wooden spoon to hit us with,” Liz van Noggeren, 46, told me. “She broke that wooden spoon on me more than once.”

If you strike a child enough times and with enough force with a wooden spoon, it will shatter. Many of the people who wrote to me about their childhoods had spoon after spoon broken on their thighs and backs. At 23, Riley refuses to have one in her house. “I don't even keep them in my kitchen for cooking purposes,” she said. “They're not allowed in my house at all.”

Wooden spoons are insulated and relatively nonreactive and are excellent implements for stirring even the hottest and sourest of things. They are also instruments of pain that linger in the memory far longer than any taste could linger on the tongue.

I started researching evangelical Christian corporal punishment quite recently, though I had known for years it was and remains a common practice in millions of American households. Knee-deep into parenting guides that read, to me, like alien and sadistic torture manuals, I realized I wanted—and needed—to supplement my reading with the voices of people who had lived with the tactics laid out on paper. So I put out a simple Tweet, asking people who had had such childhoods to reach out to me for a research project.

The response was immediate, and wide-ranging, and intense. Within 48 hours, one hundred people had reached out to me, sharing pieces of their stories on email and DM. Within 72 hours, fifty more had reached out. I wound up designing a 12-question survey—What was your experience of corporal punishment like? What parenting books or doctrines do you recall your parents using? Do you feel childhood corporal punishment has affected you as an adult?—and the responses contained so much candid anguish I marveled the words didn’t etch holes in my screen.

I do not have children, and the people sending their stories to me were for the most part talking to a stranger, a childless Jew, no less. I have only ever used a wooden spoon for stirring soup, or scooping up fried onions. Their experiences were harrowing; it’s an axiom in journalism that people experiencing bliss and contentment are unlikely to reach out to us, a profession that deals in power and in pain, unless they are trying to sell something. The people who reached out to me had nothing to sell; all they wanted was to prevent anyone else from going through what they had experienced when they were too small to defend themselves.

Respondents ranged from 22 to 65; many were my age, in their early thirties. Above all, they were grateful someone was paying attention. Someone wanted to talk about what had happened to them. People who have left evangelical denominations have their own thriving and pained and joyous communities online—in Facebook groups, on blogs like Patheos and Recovering Grace, and podcasts like Kitchen Table Cult and Exvangelical. But many expressed to me that the feeling of an outsider examining what they had been through, and finding it horrifying, was in and of itself validating: the act of observation, the act of listening, was almost enough, in and of itself. So I set out to tell this story—their stories: a story about the American evangelical culture that gave rise to a doctrine of systematized child abuse; about how it developed and why; about the theology that says to refrain from beating your children is to declare yourself better than God, and exposes them to the risk of eternal damnation.

Hitting Children

As it is with so many things—capital punishment, guns, health insurance—the United States is an outlier in the developed world when it comes to hitting children. (Use any synonym you like: spank, swat, pop, discipline, chastise—what you’re talking about is striking a child with the intent to cause pain.) Corporal punishment of children is outlawed completely in 63 countries; in the U.S., it is legal in all fifty states. With paddles, fists and palms, with spoons and switches, it is permissible—and in many social contexts encouraged—to punish children physically for any misbehavior. Hitting children has the support of the Supreme Court. In nineteen states, hitting children is permitted in public schools.

Among the general populace in the United States, support for hitting children is quite high—37%—though it has lessened in recent decades: the overwhelming scientific consensus is that physical punishment offers no benefits to children whatsoever and puts them at significant risk of both mental and physical health issues throughout their lives. But there remains a broad and widening gap between evangelicals’ perceptions of spanking and those of the general public. Roughly half of evangelicals support spanking, and those who do seem to believe in it fervently. According to Pew Research, evangelicals make up 25% of the American population. Half of that is forty-one million people.

Evangelicals are an enormously influential bloc, both culturally and politically, and have spent the past half-century mobilizing. But too often coverage of of the group is an odd mix of undue deference—uncritically reproducing the propagandistic notion that fundamentalist communities are the pinnacle of “family values”; conflating white evangelicalism in particular with a kind of “real” Americana—and dripping, aw-shucks condescension that views the ideas and experiences of evangelicals as fundamentally ignorant and unserious. Vanishingly few national reporters come from evangelical backgrounds. The truth is that evangelicals are not monolithic on the subject of hitting children. But just beneath the surface of too many evangelical childhoods is an ocean of pain.

Corporal punishment of children is, of course, not new. It is—as many evangelical theologians and parenting experts would have you know—as old as the Bible itself. Children are small and unruly beings who toddle and scream and love you with every cell, and need you for all things until they don’t anymore. And for all of time, some parents have used the flats of their hands or the nearest object to quell sleeplessness or squalling. It is probable that most readers will have undergone some form of corporal punishment at one point or another in their childhoods, whether in a spirit of judicious discipline, or in a moment of untrammeled parental anger. It is unlikely, however, that they will have undergone such treatment daily, let alone for the sake of God, in the full belief that should the rod be spared, the child risks being consigned, forever, to hell. That is the reality for many evangelical Christian children, pinned under an unsparing theology that has developed in bestselling books, charismatic ministries, and home-schooling curricula over the past fifty years.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

The Political Roots of Child Subjection

In 1970, an obscure child psychologist named James Dobson published a book that would come to spearhead a movement toward biblical parenting. He positioned it as a necessary curative for the permissive, sinful culture that swept through America in the sixties. The book proclaimed its “countercultural” status in the title: Dare to Discipline. Dobson’s vision was undergirded by repulsion at widespread social chaos, and at its core was his solution: the enforced submission of children to absolute authority.

The emergence of evangelicals as an active right-wing political force on the American scene came into full force over the subsequent decade, largely as a backlash to the civil-rights movement and school integration. In tandem, and in ways that are complexly intertwined with an overweening political agenda, a new vision of the domestic sphere arose in popular books, ministries and churches. Raising the specter of student-led activism—the antiwar, civil rights and feminist movements—a new generation of evangelical leaders portrayed strict discipline in the home as a solution to social disorder.

“In the last half-century, Conservative evangelicals were coalescing as this partisan political movement and coalescing around a particular cultural orientation, and childrearing is right at the center of that,” Kristin Kobes du Mez, historian and author of Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, told me. “Out-of-control children were unravelling the social fabric of the country. So it was absolutely critical for parents to get their kids in line. It started in the home: you discipline your kids, and then your kids will grow up to be functioning members of this social order, which was always understood in a hierarchical sense. In the 1970s, disciplining children became thick with meaning in evangelical spaces, as part of this political mobilization but also more fundamentally as part of this oppositional cultural identity.”

By the 1990s, propelled by the success of Dare to Discipline and its sequels (The Strong-Willed Child, Temper Your Child’s Tantrums), Dobson’s ministry, Focus on the Family, was a media empire. Its radio programs, educational materials, and newsletters became, as du Mez puts it, “a fixture in the homes of tens of millions of Americans.”

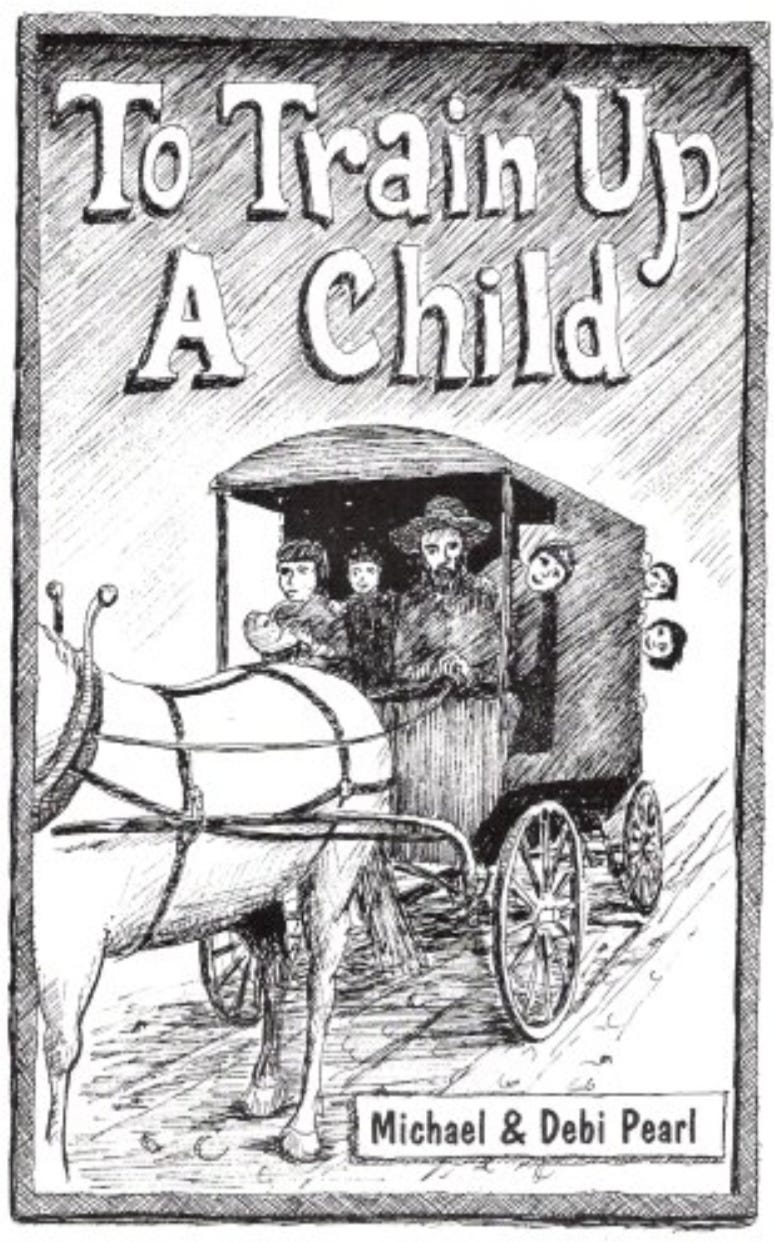

Legions of imitators followed, some more sadistic and others more faith-centric than Dobson’s unnervingly folksy persona. They continue to shape evangelical parenting culture by impressing the perils of “sparing the rod.” Dobson popularized a vision of parenting as a battle whose goal was the complete subjection of the child’s will, with pain a central tool in an ongoing spiritual war. His successors include Michael and Debi Pearl, whose work through No Greater Joy Ministries includes the infamous To Train Up A Child (1.2 million copies sold), a work that I can best describe as a child-abuse manual. There are also gurus like the pastor Tedd Tripp, whose Shepherding A Child’s Heart erases completely the line between physical abuse and parental love. Tens of millions of children have been raised with these principles, and this pain. At least three killings have been linked to the parenting doctrines of the Pearls: between 2006 and 2010, Sean Paddock, 4, Lydia Schatz, 7, and Hana Williams, 13, all died brutal deaths at the hands of parents who owned copies of To Train Up A Child.

Dobson’s The Strong-Willed Child (1978, reissued 2005) divides children broadly into “strong-willed” and “compliant”; it is primarily a guidebook in how to transform the former into the latter, creating pliant and submissive children through judicious blows.

“I remember reading my mom's letters or diary about how she wasn't sure what to do about my ‘strong will’ and she just couldn't break it,” says Joy, 37. “Looking back, I have no idea what I did that was so strong-willed. I remember her telling me a story about her telling me not to touch a plant when I was crawling and that I grinned a big ‘knowing’ grin and went and touched it anyway. I would tense myself up to endure hours of spankings. I felt that showing pain would mean they won.”

Authoritarian parenting in a religious context, asserts author Janet Heimlich in Breaking Their Will: Shedding Light on Religious Child Maltreatment, serves to perpetuate a worldview that devalues individualism for the sake of the collective and the church. (A version of this ethos can be found in a commonly-used acronym in evangelical education: children are taught to value JOY—Jesus, Others, Yourself, in that order). By dictating the ways parents raise their children, urging them to adopt corporal punishment and other authoritarian methods, parents are forced to relinquish autonomy. “Despite talk about the importance of family cohesion, family bonds in authoritarian cultures—especially the parent-child bond—threaten those collectivist cultures’ overall goals,” Heimlich writes. In this sense, harsh discipline serves both the breakdown of individualism and the perpetuation of the church itself.

Absolute Obedience

The theology represented by Dobson, the Pearls, Tripp and others (L. Elizabeth Krueger’s ghastly Raising Godly Tomatoes, Pastor Jack Hyles’ How to Rear A Child, and the fearsome Babywise creed of Gary and Anne Marie Ezzo) is one of total obedience, enforced by physical punishment and the fear of damnation. It is vital, each of these authors say, to start early, utilizing violence as early as five months (per the Pearls) or fifteen months (per Dobson). To train often, and consistently, and relentlessly. To extinguish undesired behaviors completely. To subject not just behavior, but the will.

Reading these books felt ghastly. The pit in my stomach deepened as I read descriptions of children as tyrants, anarchists, belligerents and hardened revolutionaries. There seemed a sense of palpable disgust, even rage, towards children. In Dobson’s The Strong-Willed Child, he urges parents to conquer the “willful, haughty spirit and determination to disobey” of their kids: “The child has made it clear that he’s looking for a fight, and his parents would be wise not to disappoint him!” Both Dobson and the Pearls aver that children who cry too hard after spankings are being manipulative, and should be spanked again, to silence their tears.

There is a theological root to this attitude: though not yet morally culpable or fully mature, the child is still a representative of fallen man, subject to the lusts of the flesh and the depravities of sin. “Your children need to be convinced that they have defected from God and are covenant-breakers,” writes Ted Tripp. Thus children require discipline and command; without firm guidance and enforced submission to Godly authority, they will lead themselves into the spiritual wastes. Or, as Michael Pearl puts it: “As you train your young child, you must take into consideration the evil that a self-willed spirit will eventually bring.”

“I specifically remember my mom paraphrasing sections of To Train Up A Child while she was spanking me,” said Amalia, 30. “Nearly every time my mom spanked me she'd cry and beg me to ‘give in’ so she could stop spanking me because she hated doing it so much. This touches on what I think is one of the most sinister parts of corporal punishment advice in Christian circles: the idea that a parents' instinct to shield their child from pain is ungodly and that instead the best parents will intentionally inflict pain. Linking a parent's willingness to spank to not only the child's success but the parent's spiritual wellbeing is a powerful motivation.”

In this moral universe, the ideal child is not necessarily smart, or ambitious, or even kind or loving. Above all, he or she is obedient. Every one of the respondents said obedience was strongly emphasized in their homes—central, mandatory and necessary, extending not just to outward behaviors, like making a bed or cleaning a table, but to the mien of the child performing these duties, which must, invariably, be cheerful and compliant. As Kristen Arnett told me, “defiance included rolling your eyes, back talk, or even using a sour tone.”

“Almost every spanking I’ve ever received was a result of me asking ‘why?’” says Jane, 34, of her parents. “I think they really tried to break me of ‘defying authority’ because they felt it was necessary for me to be a good Christian and a productive member of society and a good wife.”

The methods of enforcing such subjection vary: one may reward, or cajole, but above all, one must punish. For Dobson, the Pearls, and Tripp, physical punishment of children is not an optional matter, just one among many other methods of discipline. It is central to childrearing—or “training,” as it is often put—and it comes directly from God. Each of these authors quote extensively from the Old Testament’s Book of Proverbs. Their interpretation is, in typical evangelical fashion, absolutely literal. On Amazon, you can buy a wooden “Child Discipline Paddle” with the words “Proverbs 29:15” on it: “The rod and reproof give wisdom; but a child left to himself bringeth his mother to shame.” In particular, Proverbs 13:24 stars in the theological drama of these books: “He that spareth his rod hateth his son: but he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes.” Following closely on the heels of this central verse are the unyielding, dual echoes of Proverbs 23:13-14: “Withhold not correction from the child: for if thou beatest him with the rod, he shall not die. Thou shalt beat him with the rod, and shalt deliver his soul from hell.” (Many mainstream biblical scholars call this an egregious misreading of scripture.)

The upshot is to leave parents with the impression that any reluctance to hit their children is born not of love, but of selfishness and pride; and not to do so is a form of spiritual damnation of the child, a far greater cruelty than physical pain. For Dobson, spanking is both a laudable way to instill discipline and also a Biblical mandate. “The parent’s relationship with his child should be modeled after God’s relationship with man,” he writes in The New Dare to Discipline (1992). “This same love leads the benevolent father to guide, correct, and even bring some pain to the child when it is necessary for his eventual good.” God created pain, the reader is told, “as a valuable vehicle for instruction”—and “minor pain” inflicted by parents can avert “dangers in the social world, such as defiance, sassiness, selfishness, temper tantrums” and “deliberate misbehavior.” Dobson recommends squeezing the trapezius muscle at the back of the neck to control children of all ages. Multiple people said that as a result of this method, any touch on the shoulder makes them flinch.

For 32-year-old Sarah, childhood routinely featured wooden-spoon beatings until she showed sufficient “repentance.” To this day, she says, “Being struck causes me to feel sick to my stomach, even if it’s something as small as being brushed by a paper airplane.”

“The God who made little children and therefore knows what is best for them has instructed parents to employ the ‘rod’ in training up their children,” contends Michael Pearl. “To refrain from doing so based on a claim of love is an indictment against God Himself. Your actions declare that God does not desire what is best for your child and you are wiser than is he.”

Cher, 30, wrote to me about the first memory she has of her childhood.

“I was young, probably around age 4, and I remember this experience very clearly yet remember almost nothing else from that age. We had been out in public. I'm pretty sure that the initial infraction was I started crying when my dad went to zip up my coat... By the time we got home the punishment being dealt was 100 hits without any pants or underwear. My dad didn't skip a single one. I just remember hearing my own screaming and wondering if it would ever end.”

Ali Thompson, 43, told me that ADHD prevented her from always accurately understanding the orders she was given; as a result, she was beaten three to seven times a day for years. “I believe the only thing my father cares about is obedience,” she says. “Anything I did or didn’t do was a failure of obedience and all of those failures were automatically deliberate defiance.”

Evangelyn, 44, who recalls being beaten with electrical cords, belts, yardsticks, willow switches, ping-pong paddles and fishing rods, told me that obedience—and the consequences of disobedience—extended far beyond external behavior. “Not only should you obey but obey willingly with no rebellion in your heart and with a cheerful attitude,” she said. “I got spanked for not cleaning my room fast enough once, and when I went back to cleaning after my spanking, I had a depressed—or ‘rebellious’—attitude, so my dad made me sing a cheerful hymn while I cleaned and if I didn't sound happy enough I would be spanked again.”

“Confrontation, with the immediate and undeniable tactile sensation of a spanking,” writes Tedd Tripp, “renders an implacable child sweet.”

In the world of this theology, a happy child is one whose will has been surrendered utterly, to the authority of parents, and then to the authority of God: a child whose will has been broken. Broken-willed children grow up, though. And sometimes they mourn what they lost in the process.

“I don’t know what it was about me that made me so ‘strong-willed’ and difficult to control,” Lindsey, 37, wrote to me. “But I fucking want it back.”

What is lost—in subjection and pain, in fear and shame, in a submission so complete it entails self-erasure—may never return, though, with work, bright shards can be extracted. Many people who wrote to me said that after a childhood of obedience training, they were unable to assert themselves at work, make decisions, raise their voices or initiate even healthy conflict with friends or spouses.

“I have a constant fear of failure and a lot of anxiety around succeeding. It damaged my ability to be creative, and to be willing to stand up for myself or set boundaries,” Jeremy, 37, told me. “I have felt as though I had no real goals of my own without someone telling me what to do. I still struggle mightily with taking initiative and fear of punishment.”

The wages of this particular evangelical parenting philosophy are stifled selves, sparks of defiance quietly snuffed out in a self-protective inner darkness.

Books like Dobson’s and the Pearls’ offer stark and unsparing visions of a domestic sphere circumscribed by hellfire. But behind every page is the snap of a belt on children’s thighs; every rustle of paper is a precursor to the sound of a wooden spoon whistling through the air.

Part II: Love, pain, and evangelical corporal punishment

The response to the first installment of this series exceeded every expectation I had. Many readers felt moved to share painful aspects of their childhoods, for which I continue to feel enormous gratitude. One of the privileges of being an independent journalist is that I am not bound by convention to present opposing sides in tandem—not required, in this case, to neutrally present the equivocations of those who professionally advocate for striking children. What I have learned, however, is that many people who advocate physically hurting children are happy to do so for free, and entirely unasked.

I am not in the business of telling strangers what, in their own lives, constitutes abuse; that is best determined through painstaking self-examination. Roughly half the country approves of corporal punishment, among the secular and religious, the rich and the poor, the urban and rural, and across racial lines.

That being said, I will make my position clear from the outset: I believe striking children is a profound moral wrong, and offers no help, but only harm. In this conviction I am joined by such groups as the American Psychological Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, on the basis of half a century of research. Many parents who love their children feel duty-bound to strike them. If as a result of this work one fewer blow falls in one fewer nursery, it will have more than served its purpose.

—Talia Lavin, November 1, 2021

Where do the inner maps that guide us through life originate? This emotional cartography is drawn from our earliest memories, and carves grooves of nerve and sinew that lead our steps for the rest of our days. The landscape can be sunny or forbidding, depending on what we’ve experienced—it can lead us toward love, or toward pain.

In Dare to Discipline, the evangelical patriarch James Dobson recounts an anecdote that appears both foundational to his parenting approach and deeply Freudian. The day, he writes, “shines like a neon light in my mind”: he had sassed his mother, she reached out to grab the nearest object, and her hand landed on a girdle. “Those were the days when a girdle was lined with rivets and mysterious panels. She drew back and swung that abominable garment in my direction, and I can still hear it whistling through the air. The intended blow caught me across the chest, followed by a multitude of straps and buckles, wrapping themselves around my midsection. She gave me an entire thrashing with one blow!” It was the last time he sassed her, he says, though he has shared that story “many times through the years” on his way to becoming one of America’s foremost proponents of corporal punishment in the home.

“There's something about being beaten in such a religious, ritualistic, intimate way that feels almost sexual, even if it's not intended as such,” says Heather, 40, one of the many women who reached out to me for this series. “Child me picked up on that too, and started having sensual feelings about it. And felt extremely guilty for that, and wanted it to stop, but those thoughts intruded in my head. So much that I asked God to kill me. He didn't.”

What does it feel like to be struck as a child? Children feel pain, as any human being does; there is no stage of development at which nerve endings are less sensitive, at which the hot and ancient wires that connect pain to fear and fear to survival are unformed. To be struck as a child is to experience pain and fear.

To be struck as a child by your parent is to experience a different kind of pain entirely, an inextricable entanglement of emotional and physical suffering. It is a violative and bewildering moment, and the lessons it imparts are rarely those the parent sought to convey—to go to bed on time, to refrain from sibling conflict, to get better grades. Memories of the infraction fade, but a sense of betrayal lingers, as well as the sense that love and pain flow from the same font; that the child, through his or her fundamental flaws, provoked the violence they endured from their idolized parent.

Many of the Evangelical parenting authors I have read for this series declare that after inflicting physical pain, the parent must declare that “the slate is clean”—that the sin has been forgiven, and parental opprobrium with it. But in the body and the mind of the child, the nerves themselves sing against tabula rasa. The pain you carry in your body as a child grows with you; it changes how you see love, how you see violence, how you see yourself in relation to the two. The parents of my correspondents may not remember administering these beatings, or may justify them still. As one African proverb puts it: “The axe forgets, but the tree remembers.” My inbox is full—bursting—with memory: I remember… I remember… I remember my father … my mother… My inbox is full of beatings experienced now as vividly as they were at four, at seven, at twelve.

“At the Base of the Back, Above the Thighs”

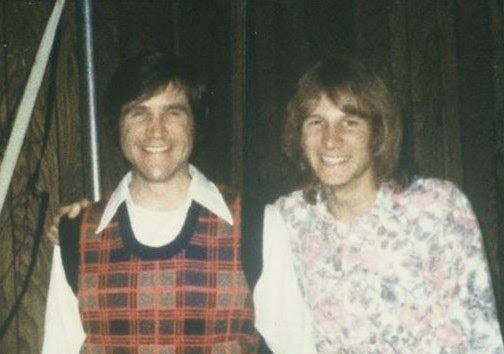

In the mid-1970s, Larry Tomczak, a charismatic, clean-cut neo-Calvinist pastor, met a peripatetic, long-haired “Jesus freak” named C.J. Mahaney in Washington D.C. Both Tomczak and Mahaney shared a love of impassioned worship, filled with music and speaking in tongues. They began to collaborate on Sunday services, and, in 1982, founded Sovereign Grace Ministries, a new evangelical denomination whose adherentssought to “live by every word that comes from the mouth of God.” Sovereign Grace would eventually encompass some 100 churches and 28,000 adherents.

In the same year Sovereign Grace Ministries was founded, Tomczak published his first book, a manual on Biblical parenting. It was called God, the Rod, and Your Child’s Bod: the Art of Loving Correction for Christian Parents. The book was pushed on church parents, and formed a crucial pillar of an approach to child-rearing that emphasized immediate and unquestioning obedience, encouraged homeschooling, and focused heavily on the innate sinfulness of members of all ages.

In 2012, eleven plaintiffs filed a lawsuit against Sovereign Grace Ministries, alleging that church leaders had carefully orchestrated a wide-ranging coverup of child molestation and abuse throughout the 1980s and 1990s. A woman using the pseudonym “Carla Coe” alleged that Tomczak had imprisoned and starved her over a 25-year period extending from her childhood to her early adulthood.

“On multiple occasions, including occasions after Carla Coe reached the age of majority, Defendant Tomczak forced Carla Coe to strip out of her clothing against her will, and be beaten on her bare buttocks,” the complaint read. “Defendant Tomczak continued to engage in this forced undressing and beating of Carla Coe until she fled and escaped from the abuse.” The lawsuit was dismissed in 2013, on the grounds that all but two of the plaintiffs had exceeded the statute of limitations for child sex abuse cases. No court ever examined the truth of the allegations; Tomczak denies them.

“Where should the rod be administered?” asked Tomczak in God, the Rod and Your Child’s Bod. “God, in his wisdom, prepared a strategic place on our children’s anatomy which has enough cushiony, fatty tissue and sensitive nerve endings to respond to Spirit-led stimulation. The area is on the base of the back, above the thighs, located directly on the backside of every child. All children come equipped with one!”

“Corporal punishment is inherently sexual because it involves ritualized contact with sexual organs,” Katherine Mitchell, 32, told me. “Every position I was put into as a child to be hit is also a sexual position that adults use. The muscle memory is still very linked and there are times that my partner and I have to stop interacting because I am having a flashback.”

Throughout this series, I have resisted using the word “spanking” unless directly quoting a source. This is mostly because I find the term euphemistic—it is an all-too-cute word for striking a child with the intent of causing pain. But the other reason is that spanking is, in the adult world, an exclusively sexual term. Well-administered slaps on the ass can add fervor to foreplay; in the context of kink, slapping can be only a start, and sex, for some fervent fetishists, an amuse-bouche compared to the act of erotic punishment. On Amazon and Etsy, a search for “spanking paddles” conjures an array of items, some overtly fetishistic—black leather, embossed red hearts—and some clearly designed for hurting children. The helpful, algorithmically-assisted autofill adds two options to guide your “spanking paddle” search: the first is “spanking paddle for sex,” and the second is “spanking paddle for kids.”

Among adults, spanking is either consensual and thrilling, or nonconsensual and abusive—a crime of sexual battery. By contrast: In many of the states in which

some 100,000 schoolchildren are subject to legal corporal punishment each year, parents must sign consent forms signaling their willingness to have their children spanked by strangers, with hands or wooden paddles—absent the child’s input about their own body. (It is easily surmised that a child whose parents consent to such punishment will not find respite from it at home, or anywhere else.)

Adult spanking and child spanking are fundamentally the same act—the deliberate infliction of pain to the buttocks—but socially, they are worlds apart. Because spanking is so common in American households, this aspect of corporal punishment is rarely discussed. But for some children, it becomes a lifelong source of sexual disquiet.

The author Jillian Keenan, a self-confessed spanking fetishist, writes in her memoir Sex With Shakespeare: Here’s Much to Do With Pain and More With Love, that given her proclivities, vicious spankings by her unstable mother felt to her like a profound sexual violation. Memories of being spanked with a hairbrush caused her, many years later, to vomit violently at the recollection. Parents may not intend to sexually harm their children through spanking, but that, Keenan argues, doesn’t matter when compared to its effects. Moreover, with regards to that intent, she asks: “Are you sure? … How much would you gamble on that certainty?”

There’s an unmistakable sensuality, even a certain lasciviousness, with which the authors of these parenting manuals fixate on the physical aspects of Godly punishment, whose locus is the buttocks. This can lead to passages that read somewhere between comical and horrifying, particularly given the endless repetition of the word “rod.” “The rod is somewhat of a mystery in how it works,” writes Ginger Hubbard in Don’t Make Me Count to Three! A Mom’s Look At Heart-Oriented Discipline,“but we can be confident that while we are obeying God and working on the buttocks, God is honoring our obedience and working on the heart.” Both Roy Lessin (author of three separate books on childrearing, including Spanking: A Loving Discipline and Spanking: When, Why, How?) and J. Richard Fugate (author of What the Bible Says About… Child Training) specify prescribed positions for children to take during the administration of blows. Fugate, who went on to lead two separate Christian home-schooling curriculum companies, suggests “over your lap for a one-year-old, laying on the bed for a two-to-four-year-old, or bent over holding the ankles for older children.”

Most of the people who wrote to me for this series experienced corporal punishment as a physical and psychological violation—as violence, and as emotional pain. But some had more to say. For girls raised in an evangelical culture with a primary focus on modesty and purity, the prospect of having to strip bare before their fathers to be struck was humiliating, a source of profound shame and discomfort.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Liz Van Noggeren, 46, recalled the sexualized humiliation of one specific beating. “I don’t know what precipitated this particular assault. What I remember is being taken down the basement and my Dad grabbing an old 2x4 and beating me across the ass with it,” she said. “The rough edges and the nail heads in the old wood made a bloody mess of me, despite my clothes. Afterwards, once he’d calmed down, he had me lay on my tummy on my bed and exposed my bare ass and spread ointment on the bruised and bloody skin. I couldn’t sit in a chair for some time, but the revulsion of him touching my bare ass when I was 11 or 12 years old stayed with me far longer.”

For other respondents, the connections were more vivid, even from an early age. Amelia, 30, recalled that being forced to strip created guilt and confusion—an extreme form of immodesty.

“I had separately ‘figured out’ masturbation as a toddler (obviously without knowing what it was), and would often use it to self-soothe before and after getting spanked,” she wrote. “The combination of authority figures forcing me to get naked and endure pain; blood rushing to the general area from the spanking itself; and masturbating afterwards to calm down created early connections between shame, pain, and sexual pleasure that were definitely inappropriate. I don't remember how early it was, but I know it was before the age of 6. As an adult, I believe corporal punishment is virtually always physical abuse and often sexual abuse as well.”

The buttocks and genitals are anatomically very close to one another, and the percussive contact of a hand or a paddle causes a flush of blood to the region. The same blood courses down the same, bifurcated artery during arousal. As Keenan puts it in her memoir: “Children have emerging sexual identities. And if even 1 percent of them perceive spanking as a sex act, we are violating too many kids.”

“Pick Your Own Switch”

When she was very young, Joy remembers, her parents often sent her to the patch of weeping willows beside her home. There, she was instructed to pick her own switch—a short length of willow that would be used to beat her. When she grew older, plastic hangers and dowel rods from Home Depot were the tools of choice, but in her youngest years, she was made to participate in the ritual of her own punishment.

Joy ultimately left home at 17, winding up with a man 12 years her senior, who strangled her, beat her, and attempted to throw her out of a moving car. “I was denied autonomy, told I was evil and defiant, isolated from the world, denied friends, told I was an abomination, and beaten daily for at least 12 years of my life,” she says of her upbringing. When it came to finding a partner, “I did not know what love was supposed to feel like, I didn't know what safety or security felt like, and I found myself in abusive relationship after abusive relationship.”

Dr. Patrick Carnes, founder of the International Institute For Trauma and Addiction Professionals, coined the term “trauma bond” in 1997, in his book The Betrayal Bond: Breaking Free of Exploitative Relationships. It’s a new term for an ancient phenomenon: “attachments that occur in the presence of danger, shame or exploitation.” According to Carnes, the condition of the trauma bond is to feel “at the same time deeply cared for and deeply afraid”: it is present in both abusive childhoods and in abusive romantic relationships, and stems from the alternation of loving and violent behaviors. A young child cannot flee their parent; the inner paths formed in early years become the emotional geography of a lifetime.

“Early attachment patterns create the inner maps that chart our relationships throughout life,” writes Bessel Van Der Kolk in his groundbreaking work The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma. “Our relationship maps are implicit, etched into the emotional brain.” The carefully performed infliction of physical pain, followed by declarations of love and gentle touch, is a concretization of the trauma bond, an indelible crevasse in one’s emotional topography. Under these guidelines, the source of love and the source of pain—of hope, comfort and intimacy, as well as physical punishment—are definitionally the same. It is a lesson that can echo down the corridors of a life.

Many fundamentalist Christian parenting guides lay out a stark vision of children, one in which only strict punishment can lead to salvation. The author J. Richard Fugate—whose popular 1980 book What the Bible Says About… Child Training offers a sampler of recommended beating implements for children from ages 1 to 20, starting with the “Tot Rod,” (a 3/16” x 24” dowel rod)—describes children as “sinful, dirty and selfish.” They are born, he writes, in a state of “spiritual death.” The shocked look and tears of the baby, Fugate writes, will indicate that you have gotten his attention. Obedience must be externally imposed, and physical pain is the only means to make a child truly accept parental direction—a condition with existential stakes for their very soul.

Alice, 38, was beaten on a weekly basis with wooden spoons and spatulas until she was twelve. She was told it was the only measure that could correct her innate sinfulness.

“I stayed with one guy who would throw me around when I ‘acted wrong,’” she says. “I knew it wasn’t right, but I couldn’t articulate what wasn’t right about it. I was so used to being punished for my wrongness that he just sort of fit the pattern. I only left after he raped me.”

Jay, 28, was beaten with paint stirrers and a 2x4 with a handle shaped like the top of a picket fence. After her father beat her, he would tell her he loved her; he made her say she loved him back.

“I was in an abusive marriage for years because I believed I deserved to be hurt by figures of authority,” she said. “I thought it was making me a better person or keeping me safe from myself somehow. That's inextricably linked to corporal punishment for me.”

In 2017, a landmark study of nearly 800 adults found that children who were spanked—even when controlling for severe abuse, the type doled out “in anger”—are more likely to be involved in violent romantic relationships, often as the aggressors. Otherresearch suggests that violent experiences during childhood make people more prone to both perpetration and victimization of violence in romantic relationships. In each case, the wires that link pain and love have become soldered together, manifesting in either the instinct to violently dominate or an instinct to accept cruelty.

“Hearing my parents say over and over that they hit me because they love me, that they wouldn’t have broken that spoon across me if they didn’t love me, I have love and pain entangled in my psyche,” Sammy, 34, told me. She remained in an emotionally abusive marriage for ten years, she said, because her childhood had primed her to accept it. “I felt defective and unlovable because I was told by my mom during punishment sessions during my whole childhood that if I didn’t shape up my character and behavior, nobody would ever want me for a wife.”

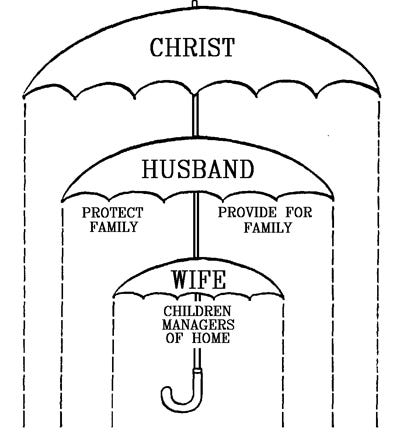

They hit me because they love me bears a remarkable resemblance to the old domestic abuser’s credo you made me do it—the very existence of the child, or the lover, has provoked the violence. In many cases the violence begins before a child can walk or speak. Beatings are only to be administered in the case of “deliberate disobedience,” but often this stems from a look, a sigh, a hesitancy, a “defiant arching of the back”; the parent is to read the child like tea leaves, forever imputing malintent. For women in particular, who are raised in a church culture whose highest ideal for them is submission and obedience to the “headship” of a husband, the pressure to react to abuse with further submission and obedience is both internal and external. In Unholy Charade: Unmasking the Domestic Abuser in the Church, the pastor and author Jeff Crippen lays out a series of theological justifications for abuse. In particular, he singles out the idea of total and unquestioning submission to authority, as conveyed in the teachings of wildly popular (and sexually abusive) Christian homeschooling guru Bill Gothard, as a means to quell “rebellion” in women who are being abused. “Teachings like this, which strike fear into the heart of an obedient Christian,” Crippen writes, “can work to keep a victim in a domestically abusive situation far past the time when the situation has become intolerable for her and her children.”

Men face their own challenges in building healthy romantic relationships after childhoods of enduring corporal punishment. Both men and women who had avoided physically abusive relationships wrote to me of enduring struggles in building and maintaining emotional openness, hindered by fear that love and vulnerability would invite further pain.

“I believe my experiences of corporal punishment impacted the way I experience emotions. I can't be certain that's the cause but I am certain it didn't help,” says Jeremy, 37. “I have yet to have a successful romantic relationship with a woman; I'm not sure that I want one and I'm not sure I'm capable of experiencing love or romantic feelings.”

“I carry a paralyzing fear of screwing up, being less than perfect, having thoughts which I find immoral,” said Paul Rust, who grew up in the Franklin Baptist Church. “I find it extremely rare to feel safe in any environment, even my home.”

If an internal map is built on violence—with punishment and control its chief features, the peaks and troughs etched out in dominance and recrimination—the guidance it offers can lead to a similar landscape in adulthood. The compass points towards both pain and love, and they are found in the same direction, an inner north that pulls and pulls the pliant heart into the wastes.

Part III: Breaking the cycle of abuse, brick by brick

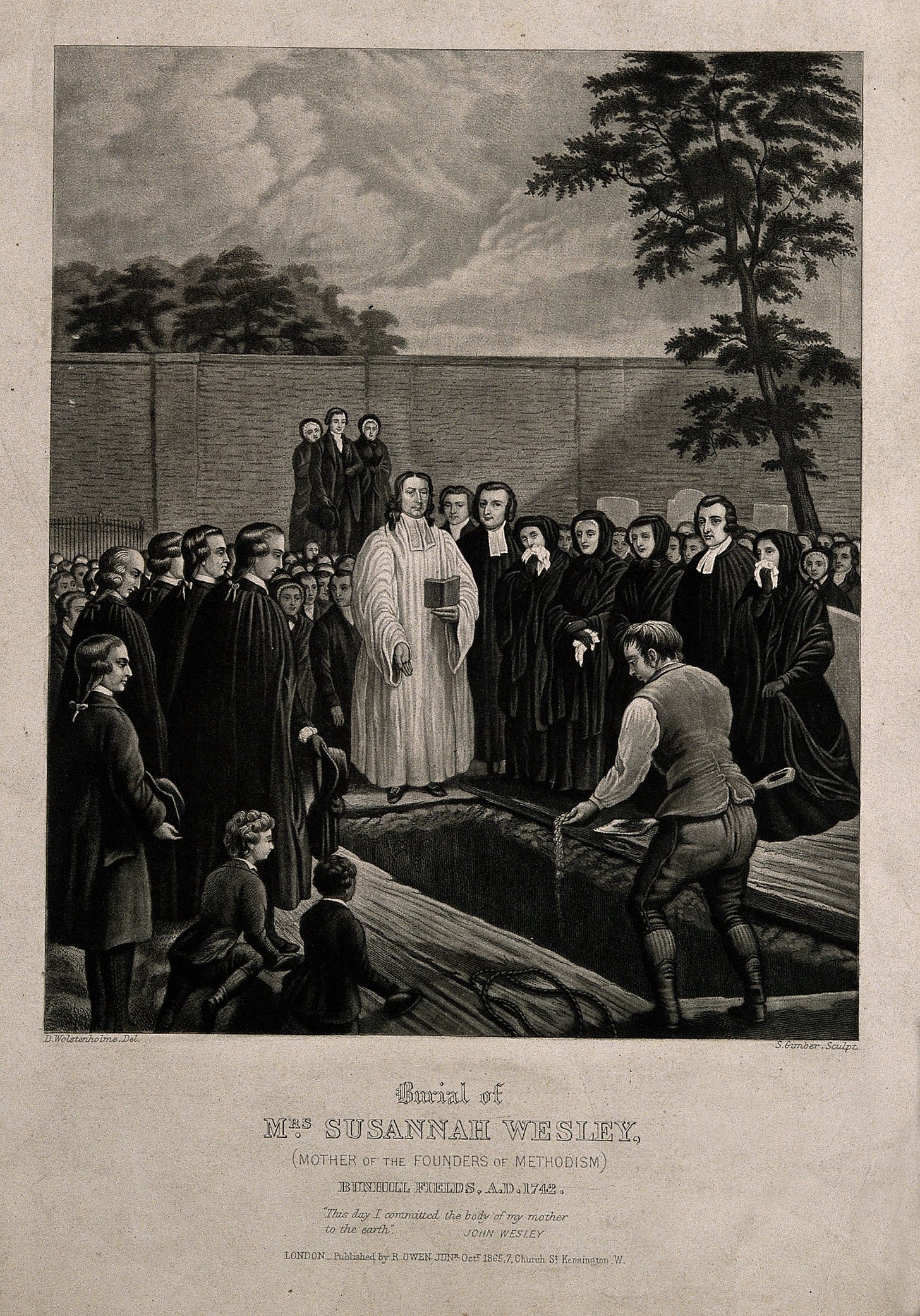

All across the dreary little swamp of evangelical parenting books I’ve waded through over the past month, one woman floats to the surface again and again. She’s not a Biblical matriarch, nor any of the seven hundred wives of King Solomon, the purported author of the Proverbs that guide the punitive fundamentalist Christian approach to childrearing. She lived on the cusp of modernity, and died thirty-four years before the United States was founded. Her name was Susanna Wesley, the mother of John and Charles Wesley, founders of Methodism; she was something of a kitchen-table lay preacher in her time, and the wife of an eccentric who squandered the family’s scant funds on writing a quixotic exegesis of the trials of Job. She bore nineteen children.

Though enough of her writings survive to fill a sturdy volume, it is primarily one piece of correspondence that is quoted in Protestant circles of different denominations. The letter concerns not her role as a prayer leader nor her commentaries on the Ten Commandments or the Apostles Creed. It is in regards to her methods of childrearing, which she outlined in a letter to her son John in 1732:

“When they turned a year old (and some before) they were taught to fear the rod, and to cry softly. By this means they escaped abundance of correction they might otherwise have had. That most odious noise of the crying of children, was rarely heard in the house. The family usually lived in as much quietness, as if there had not been a child among them…

Drinking or eating between meals was never allowed, unless in case of sickness, which seldom happened. Nor were they allowed to go into the kitchen to ask anything of the servants when they were eating. If it was known they did, they were certainly punished with the rod…

… When a child is corrected it must be conquered. This will not be hard to do if he is not grown headstrong by too much indulgence. When the will of a child is totally subdued, and it is brought to revere and stand in awe of the parents, then a great many childish follies, and faults may be past over. Some should be overlooked and taken no notice of, and others mildly reproved. No wilful transgression ought ever to be forgiven children, without chastisement, less or more, as the nature and circumstances of the offence require.”

The evangelical-parenting industrial complex has a number of devoted Susanna Wesley fans. Notably, James Dobson quotes the 1732 letter at length and with approval in The Strong-Willed Child, advocating for parents to extinguish the “rampaging will” of their children. Larry Tomczak, in God, the Rod, and Your Child’s Bod, notes that thanks to Susanna’s discipline, John and Charles Wesley “shook two continents for the Lord.” Her influence is not limited to Reagan-era evangelicals. In his 2010 book In God We Trust: Why Biblical Authority Matters to Every Believer, Steve Ham, senior director of outreach for Answers in Genesis, a creationist ministry that provides homeschooling materials and runs two enormous Bible-themed museums, lavished praise on her as the ultimate exemplar of Christian motherhood—“the highest calling.”

The nature of that calling was stark in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Susanna lived until she was 73 years old, long enough to witness the death of eleven of her children. Eight died before the age of two, one accidentally smothered by a nurse. Susanna was nearly continuously pregnant from 1690 to 1709. It is in this context that one must consider her contention that the crying of children is the “most odious noise,” one to be rarely heard, and to be punished until it recedes into soft, broken whimpers.

Nonetheless, it is this bonneted, severe-looking woman to whom twentieth and twenty-first century evangelicals have turned to in crafting their parenting advice. It’s worth mentioning that Susanna’s most famous son, John Wesley, was rather more temperate in his admonition to utilize the rod of correction than his mother. In his sermon On Family Religion, published in 1762, he notes that corporal punishment, while ultimately commanded by God, should be used last, after all other means are exhausted. “Whatever is done should be done with mildness; nay, indeed, with kindness too,” he wrote, “Otherwise your own spirit will suffer loss, and the child will reap little advantage.”

What, exactly, the spirit suffers—or, suffering in the name of the Spirit—is ultimately the subject of this series: it is a chronicle, in fits and starts, by an outsider (or “infidel,” as one commenter put it), of pain inflicted on children. Those who wrote to me—and those who confessed later that they couldn’t, that they wanted to, that they feared to—were beaten with an astounding array of household objects in the name of Christ the Savior. Some parents were eager to perform the duty of punishment; others were less so, influenced by the social milieus of their churches and the doctrines of popular preachers to believe there was no other way to ensure their children’s salvation. For some children, the physical brutality of corporal punishment served as a primary source of trauma. For many others, the prescribed multi-step ritual—the waiting for the “neutral object” (a paddle, an oar, a hanger, a fishing rod, a dowel, a peach-tree switch), the coerced confession, the arrival at a state of brokenness indicated by a specific tenor of weeping, the subsequent coerced reunion with its embraces and declarations of love—was a source of enduring confusion and emotional pain. The books I have read span from 1970 to 2018: 48 years of the doctrine of absolute obedience, and generations of children raised in its shadow.

The stated reason for all of this pain is that children do not remain children. They grow up into morally culpable subjects of God and the world; in order to prosper, they must be taught to obey authority at all times; they must someday grow to instruct children of their own. And they have. Millions of them. Many have stayed within the bounds of the church, passing on, with each percussive blow, the doctrine of the rod of correction. Elisabeth Elliot, the daughter of two missionaries, wrote in her 1992 memoir The Shaping of of a Christian Family: How My Parents Nurtured My Faith about being struck with switches and hairbrushes beginning long before she could talk, having her mouth washed out with “a great bar of yellow soap,” and about the refusal to cry that earned her greater punishment. Her reaction was gratitude for her parents’ “vigilance”; these practices, she wrote, do not seem oppressive to her looking back, and though she is sure there must have been “nervousness and anxiety at times,” she cannot remember those feelings clearly.

Most people raised this way remain in contact with their parents: perhaps even, in a country bereft of affordable childcare, offering up new young bodies to their tender mercies. But others have left—for other churches, or for no church at all. Even bonds of blood, tested with sufficient force, can fray. Some families are the families you choose. And the children you raise do not have to be raised as you were.

“I do not have a relationship with my parents,” Erin Gentry, 35, wrote to me. “While it's probably for the best that we don't have a relationship, it's very painful just the same. They live 10 minutes away and I have nightmares that I see them out and about with my children.”

It is difficult, and sometimes even frightening, to acknowledge both that you love your parents, and that they have deeply wronged you. The sense of fractured authority, the internalization of endured experiences, can create a dissonance in the self. Those who have been taught to submit their wills may have difficulty seeing the gravity of injustice that has been done to them. There is a peculiar loneliness to pain inflicted by your parents, who serve, in the earliest years of life, as one’s chief sources of love, nurturance, and guidance, particularly in the social context of a close-knit religious community that prides itself on its morality. Such isolation is intentional. The teaching across fifty years of evangelical parenting books is remarkably firm on this front: spanking is “an event” and it should be done in private (Benny and Sheree Phillips, in their 1984 book Raising Kids Who Hunger for God, confess that with their large family, it feels as if “much of the day is spent in the bathroom spanking the children”). The bell jar of private pain can descend even in public, if the religious community approves of such punishment (Sheree Phillips, regarding her three-year-old son’s tantrum after she gave a parenting class in a church: “I carried my screaming child to the restroom… I spent quite some time calming Jesse down, disciplining him for his wrong attitude, re-disciplining for refusing to receive his spanking willingly, and completing the restoration process.”)

As painful as the blows is the knowledge that there will be no rescue. Sometimes that knowledge curdles in the body and the mind, coagulates and settles into anger; bruised bodies grow bigger, and not every relationship between parent and child survives. “My mother died 7 years ago, alone and miserable after having alienated virtually everyone she ever knew,” said Kate, 50, who was struck, sat on, and pinned down while her mother prayed for demons to depart her. “I have never shed a tear, never mourned her passing.”

“I remember being yelled at to stop crying after being spanked, and feeling this burning resentment towards my parents over it, because they were the reason I was crying,” wrote Ana, 35. “My relationship with them is limited to a handful of phone calls a year.”

“I have almost no relationship with my parents or siblings beyond the occasional happy birthday text and a $25 gift for the Christmas name-drawing,” said Abbi Nye, 35, who was beaten with hoses, drumsticks and spoons, starting at six months of age. “My parents and eight siblings are all caught in various cult-like churches that emphasize obedience as a primary virtue.”

Darlene, who is in her late forties, experienced 18 months of homelessness after leaving the church and being cut off by her parents. “If I ever make enough money to have a pet project, I plan to open transitional housing for single moms leaving Evangelical families,” she said. “We nearly always lose our families, and providing a place for women to start over where they don't have to struggle like my daughter and I have had to is a dream of mine. Darlene's Home for Inconvenient Women.”

Era of Deconstruction

Many former evangelicals describe the process of leaving the church as a “deconstruction,” a term that came to Christianity by way of Jacques Derrida and a handful of ambitious, academically-minded theologians. Like so many terms, it is widely known and feared in fundamentalist circles; tentatively embraced by those in the process of leaving; and unknown entirely by most outside that world. Derrida’s famously opaque disquisitions on the dismantling of everything have given way, in the hands of impassioned writers like the late Rachel Held Evans, to encouragement. During her deconstruction, she wrote in 2015’s Searching for Sunday: Loving, Leaving and Finding the Church, she “conducted this massive inventory of my faith, tearing every doctrine from the cupboard and turning each one over in my hand.” It is, she says, “a frightening road.” (Incidentally, and perhaps relatedly, postmodernism as a whole, beyond the suave white-maned figure of Derrida, has been used for decades as a catchall bête noire in fundamentalist circles, a term for the irreverence and depravity of contemporary culture; it’s a direct antecedent to the way “woke” is used in 2021 conservatism—a term emptied of anything but scorn.)

Deconstruction, as many progressive Christians would have you know, is not destruction—but it can precede the dissolution of faith. Chiefly, it is the effort to unravel all the myriad threaded-together assumptions that make up life in a stringent faith community—corporal punishment, Republican politics, submission to God, love of one’s parents, abnegation of the self, et. al.—and to choose among them, clear-eyed. “A secret cannot even appear to one alone except in starting to be lost, to divulge itself,” Derrida wrote in How to Avoid Speaking (translated 1989). Similarly, a faith cannot be examined without undermining unquestioned—and previously unquestionable—assumptions.

Those who wrote to me have complex relationships with faith: some embrace gentler forms of Christianity; others violently oppose religion of any kind.

“I will not set foot in a church again ever for any reason,” said Johnny Huscher, 40, who recalled a childhood filled with horrific pain, and whose parents are not allowed in his home. “I am extremely hesitant to allow my kids to be alone with any adult who attends church regularly.”

“I am a Christian. My primary act of worship is in caring for others as a nurse and as a professor,” said Jamie, 50. “I believe that every human is created in the image of God and that to care for them is a privilege.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Some of the people who wrote to me have chosen to never have children, so as not to inflict the cycle of abuse on a new generation. Others chose to have children, and to break that cycle by other means—often by deliberately and painfully overriding the lifetime of violent instinct that had been ground into their bodies. One man recounted to me a bemused dialogue he had with his lively son, explaining to him that he didn’t know how to do this—how to parent without violence. That they would have to figure it out together.

For Johnny Huscher, having children was an opportunity to permanently sever from the practices with which he had been raised—a decision he never questioned. “If there was a difficulty in finding an alternative,” he said, “it was because I had to learn to see parenting as being about something other than domination over a child.”

“My children were not raised with violence. But it was really hard for me to learn to inhibit, and not use violence and corporal punishment, since I was raised in a family with it,” said Lisa, 60. “I slapped my daughter once, not hard, when she was a really mouthy adolescent; big mistake, I totally was wrong and apologized profusely, and she STILL talks about it.”

Other parents’ deconstruction began after they had raised their children violently. One woman wrote to me, simply: “I can’t believe I used to hit my children with a stick.”

Marcie’s deconstruction began in 2017. At the time, she wrote, “I feel like my beliefs are like a wall or stack of bricks. Each brick represents one doctrine—like one brick represents the doctrine of heaven and hell, another brick represents the doctrine of Biblical inerrancy, another represents the idea of wives submitting to their husbands,etc… And I worry that God is mad at me for letting the bricks fall or at the very least, grieving... but the bricks are falling over and I cannot stop them.”

By then, she had raised her two sons according to the doctrines of L. Elizabeth Krueger’s Raising Godly Tomatoes: Loving Parenting With Only Occasional Trips to the Woodshed, a harsh and brutal doctrine that prescribes physical punishment, social isolation and the persistent use of shame. At the age of 18, one of her sons threatened suicide with a loaded gun to his head and cut himself with barbed wire, recalling panic attacks about repentance that began at the age of nine.

“In my opinion, he likely has PTSD as a result of how I raised him,” Marcie said. “And it is too late to fix or repair things. The damage is done. I am guilty.”

For some parents, the act of having a child was, in and of itself, the beginning of the dissolution of their faith. Their instincts—their very bodies—rebelled against striking and beating their offspring; watching their sons and daughters grow up without the shadow of punishment, they mourned their own lost childhoods, and the children they could have been.

“Not a day goes by that I don’t wish things had been different for me and my siblings as children. Not a single day,” said Erin Gentry. “I’m starting to feel more comfortable parenting myself along with my kids—silently in my own mind, but acknowledging little Erin just the same and showing up for her in the ways I needed most.”

Susanna Wesley’s grave lies in Bunhill Fields, in London, its white marble tombstone spackled with lichen. “She was the Mother of nineteen Children of whom the most eminent were the Revs. JOHN and CHARLES WESLEY,” reads part of the inscription. Her husband, Samuel, is buried nearly two hundred miles away, at St. Andrew’s Churchyard, in Epworth. Of her children who died before the age they would have been taught, with the rod, to cry softly—Annesley and Jedediah, Susanna, John, and Benjamin, and four who never had names at all—scant record is to be found. They are likely buried where they were born, in Epworth and South Ormesby, under the small infant tombstones that are more numerous the older the graveyard, and whose scant details are nearly always worn away. Despite what Susanna asserted in her famous letter, only in such a grave is the will of a child totally subdued.

If you live, you can change, slowly as a root breaking a stone, or quickly. To surrender the absolution of faith, to strike out into the unknown, to parent counter to every model you had, is an act of courage; to heal from the welts and the stripes and the scars they left in your mind is an act of courage; which is not to say that it is seamless, or perfect.

“I will probably be rebuilding for the rest of my life,” Jamie told me. “As a child, I had a strong sense of justice and fairness, and that was the beginning of the rift between my childhood and adulthood; and between my parents and me. That need to make the world a more just place is still there. I am proud of it.”

Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you, infinitum