Morning and Evening, Pt. VI

The sixth installment in an ongoing narrative, told week by week

Previously published: Morning and Evening, Parts I, II, III, IV and V

Content note: this chapter contains a scene depicting sexual violence.

Chapter 3

Yossel did not see Pawel again for many weeks. Whether the boy had taken to his lessons in earnest with the priest, abandoning his post at the top of the church steps, or whether he hid when Yossel passed, Yossel did not know. Each day fell like a coin at his feet—heavily, into the dust; and summer passed before he knew it had come.

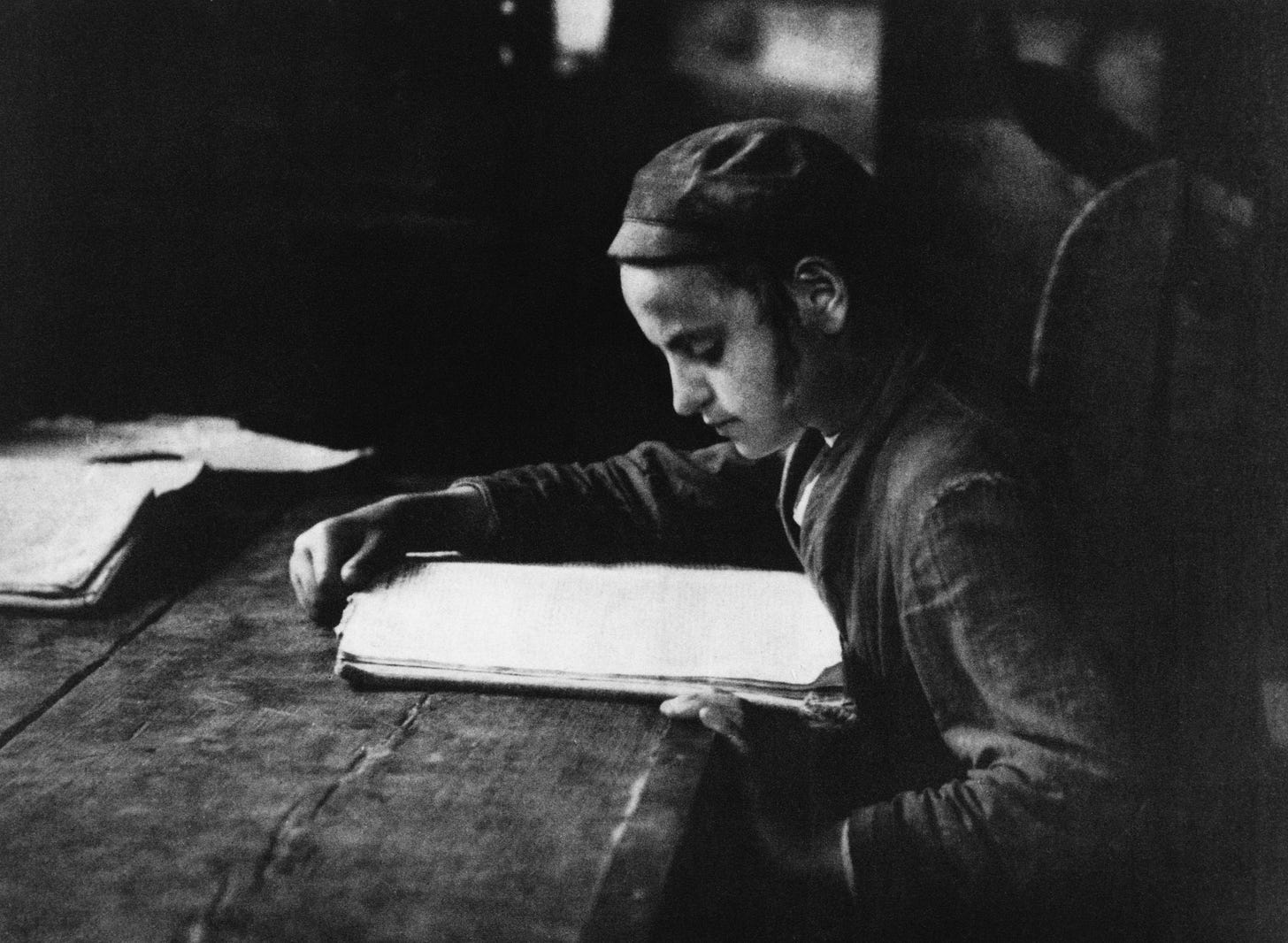

September. The leaves of the birches turned to russets and yellows, their bark white as the coming snows; but nothing emerged from the birchwood, and Yossel did not venture in alone. Soon enough his bar-mitzvah would come, for his birth-month stood at the lip of winter. He had begun to practice his portion; but the notes stuck in his throat, and his voice broke over them. Again and again the words of his portion flowed over his lips: Joseph was seized by his brothers, flung into the pit; the colored sheepskin dyed with blood, redder even than the leaves of the oaks and the alders. Again and again, Jacob bayed his grief, and cast himself into sorrowful dotage. Yossel longed to escape it; no longer did he pity Joseph, nor fear the passing Ishmaelites to whom he was sold; and once he wished, murmuring to himself, on a late evening in the gloomy study-house, that he, too, could be bound in a basket and carried out to a foreign land.

Always his mother reminded him that after his bar-mitzvah she would seek to send him away to yeshiva. It was his lot to become a rebbe—his lot to spend his days in the study-house, the lot that ought to have filled him from with pride from nape to navel. One Sabbath she woke him early, and gave him a double portion of his morning meal; beaming, she watched him eat, and her eyes brimmed with tears. She still sometimes spoke of that Sabbath he had arrived so late, with no word for himself, and with the stain of the sun on his face; and always she warned him to keep to his prayers and his books, lest she lose him to drink, or to the Christian knife and its fiery word, for God had sent him to become a rebbe of Israel. Yossel was pale now, and his eyes were black and deep. Sharply they gleamed in his white face; and his two earlocks dangled to his mouth, brown, and long grown dull in the dim light of the study-house. It was two months until his bar-mitzvah then.

When she sent him off into the morning, with many words of pride, and many warnings lest he stray, he felt himself seized by a weeping he could not contain. It had been many months since the morning she had cried out for Jerusalem, but still he thought of the white Pawel against the rock; and grim, dark and grim as a blind and dripping cavern, stretched the long years in the study-house before him. His head spun, and he turned on his heel, away from the shtiebel, where his mind’s ear had already begun to play the grim tones of Srul the butcher’s cries for the Temple, and the droning, the toneless Prayer for the Dead.

Like a blind cat, stumbling, his thin body trembling, he walked far into the fields, until the rhythm of his steps quieted his racing heart. His eyes were red and dim, and he put out his hands before him, groping at the air, as he climbed a hummock at the north end of Mystislav the goatherd’s field. Fescue in knotted strands, sharp and runny with bluish sap, pricked at his palms, and the heads of the last of summer’s flowers burst under his feet. The sharp scent of the dry blooms stung his nose; around him, hundreds of dandelions were blooming, yellow and jagged and not yet gone to seed. His head spun with the scent of the glade, with the sun on the yellowed grasses, and he felt weary of weeping. He sat to rest at the foot of the sole tree that grew on the field, a rotted yew split in two by a deep hollow, extending to its crown of boughs. The hum of bees, working on through the morning, reached his ears as if through a hushing snow, punctuated by the calls of unfamiliar birds. Sleep approached him, like a woman walking from a long way off, bruising the yellow grass as she came. He was a small dark figure against the field’s expanse, nearly invisible in the crevice between yew-roots.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sword and the Sandwich to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.