Notable Sandwich #37: Chicken Schnitzel

An ode to a working-class staple beloved in ... Australia?

Welcome to Notable Sandwiches, the series in which I, alongside my editor David Swanson, stumble through the strange and ever-changing documenthat is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week: bizarrely, a version of the chicken schnitzel sandwich that is deeply revered… in Australia.

Sandwiches are inherently a conglomeration of elements—the marriage of a particular bread with a particular array of fillings—and over the course of this culinary odyssey, I have brushed up against patterns of colonization and global migration more than once. One of the beauties of the List of Notable Sandwiches—particularly when consumed in an order as arbitrary as the alphabet—is the way it whipsaws across cultures and cuisines and continents, highlighting beloved national dishes, obscure culinary paraphernalia, and the occasional bizarre novelty. (Here’s looking at you, doughnut burger.)

Which is why it’s not precisely a surprise to encounter, this week, a chicken-schnitzel dish most popular not in Austria, the country of Wienerschnitzel’s origin, but a world away, in the antipodes.

The Australian chicken schnitzel sandwich—otherwise known as a “schnitter,” “schnitty,” “parma” or “Parmi” (the latter for its chicken-parmesan variation) is, apparently, one of the most popular and ubiquitous fast-casual dishes on the whole continent. “Schnitzel is on the menu of EVERY pub in this country,” says Van Badham, a columnist for the Guardian Australia and a friend of mine. “They’re served with chips—fat, cooked fries, and lemon wedges. My mum almost blinded someone by trying to juice a lemon wedge for a schnitzel with a fork and it hitting them in the eye. It is the bedrock of Australian working class culture.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

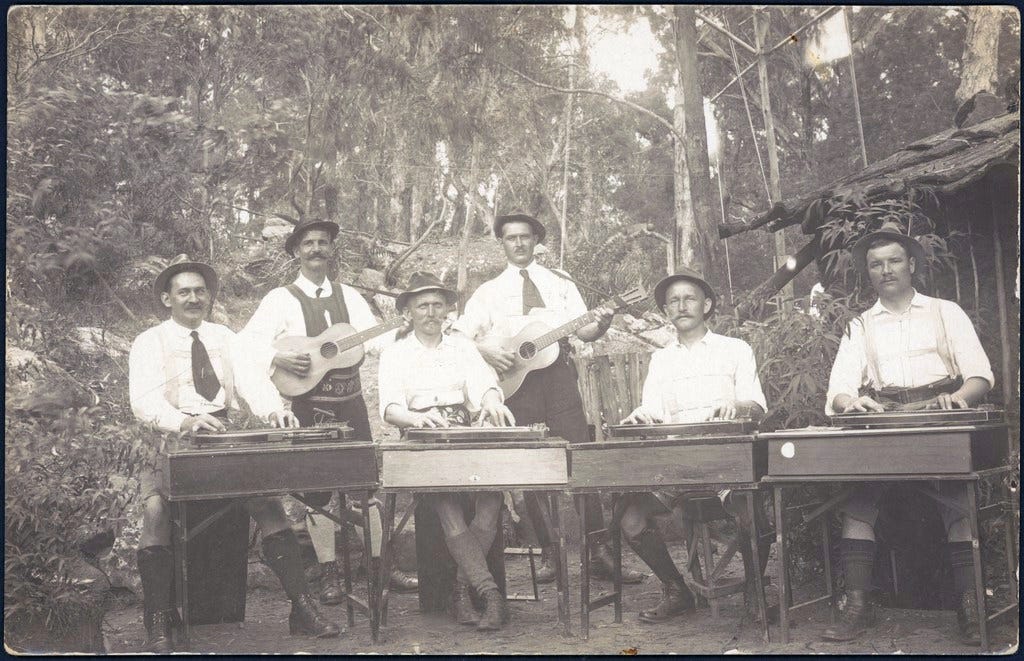

Badham theorizes that schnitzel boomed in popularity during the Great Depression, when its breadcrumb-and-egg coating served as a way to stretch meat and make frugality delicious. Particularly popular in the state of Victoria, whose German population ballooned in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the schnitzel spread alongside the wave of immigrants with the expertise to fry it. But the World Wars intervened. As the Australian poet Les Murray put it in his verse novel Fredy Neptune, about a German-Australian sailor, “What was loose in Australia? What did/that word ‘Huns’ mean for us?”

During the World Wars, strife arose between the British and German empires; in a country hopped up on wartime propaganda, German institutions and schools were closed, and German-Australian citizens—who had become the nation’s largest ethnic minority by the end of the nineteenth century—were interned in camps: 7,000 during the First World War; 12,000 Germans, Japanese and Italians during the Second. The settlement of Germantown Hill was renamed Vimy Ridge in 1918; Kaiserstuhl became Mount Kitchener, and Heidelberg became Bickley. But however many Germans were locked up or erased from their own settlements, the schnitzel they brought with them continued to proliferate, cut off from its origin, but eaten eagerly all the same.

It’s a timeless story of stolen flavor—one that resurfaces among countless immigrant groups. The same people spouting anti-Asian vitriol throughout the Covid-19 pandemic were loath to give up their General Tso’s, and the British Empire brutally inducing years of famine in India did not deter Englishmen from enjoying a spot of kedgeree down the pub.

After World War II, a millions-strong influx of Italian immigrants brought a new take on the schnitzel—this time draped with parmesan and marinara sauce, a dish known elsewhere as parmigiana. Nonetheless, the “parmi” and the “schnitter” remain side-by-side and nearly interchangeable in Australia’s eateries, fried-cutlet staples that are filling, portable, and cheap.

Today, the schnitty remains a dish Australians eat cold for lunch or hot at the pub, and you can tell how beloved it remains by the sheer number of riffs on the subject. At the Central Market in Adelaide, you can buy kangaroo steaks purpose-cut for making kangaroo schnitzel; Australian recipe guides suggest serving fish schnitzel, or breading your cutlet with quinoa. The restaurant chain Schnitz, which boasts 71 locations from Armstrong Creek to Wollongong, offers a “schnitaco,” a schnitzel-adorned Caesar salad, and the “Parmageddon,” with sauteed peppers, mushrooms and basil.

These gentrified riffs on the schnitty, Badham says, are a result of the sandwich’s status as a social marker—a dish beloved of the working class, and eaten with winking nostalgia by their upwardly-mobile progeny. “The weird class-transition phenomenon of the parmi means it’s always on the menu in big inner-city gastropubs,” she says. “They’re super popular with hipsters who are engaging in a bit of class cosplay.”

Whether it’s divorced from its class origins, or from the ethnic group that brought it down under, schnitzel in Australia appears to be a dish that survives—and thrives—despite deracination. Its combination of crunch and compressed flesh, carb and protein and golden crumb, has survived all its age-old unsavory connotations, and emerges irrepressibly onto chip-laden plates. It’s easy to do that with an object, particularly one as lovable as a schnitzel sandwich; harder to do as a person left behind; and harder still to look at the sandwich in your hand and recognize that it has a history too complex and fraught with pain to be digested in a few bites. But that’s the essence of sandwich writing: finding all the layers under the bun, and stacking them for display, whether it’s a story of migration, or internment, or colonialism, or just a tale of bright and brilliant flavor.