Notable Sandwich #47: the Club Sandwich

I don’t want to belong to any club that would have me as a member.

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the series in which I, alongside my editor David Swanson, stumble through the strange and ever-shifting document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week: a triple-decker classic, the club sandwich.

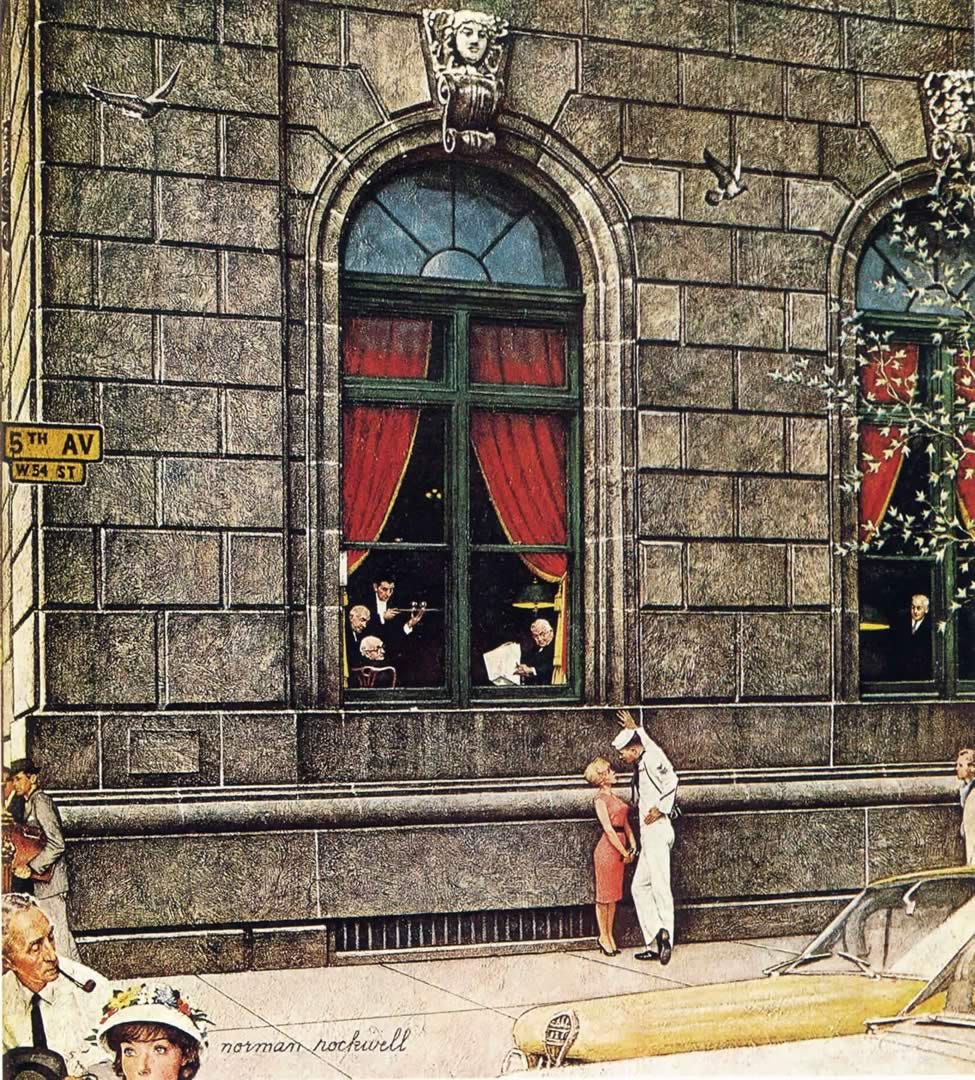

Whoever conceived the club sandwich seems to have been ignorant of the basic mechanics of the human mouth. As typically served, the dish is a teetering construction: three slices of toasted bread serving as the bricks, an array of meats and accompanying vegetables the mortar. It’s often held together with fancy toothpicks—a further hazard to the teeth, gums, palate, and tongue—and is generally impossible to bite into, as one customarily does with a sandwich, unless one has the capacity to unhinge one’s jaw like a snake. Perhaps the initial creators of the sandwich were part reptile. Certainly, they were white Christians. Though disputed, the invention is most often attributed to the Union Club, New York City’s oldest and most exclusive social club, and recipes for a dish called the “club sandwich” start appearing in the English-language lexicon circa 1903. The earliest triple-decker iteration appears in the nineteen-teens, a period when the toniest social clubs of New York, and elsewhere, served as bastions of a certain type of privilege. In other words, in cities bustling with immigrants and laborers of all kinds, no Black people or Jews need apply.

According to an excellent and thoroughgoing history of New York’s elite social clubs from Curbed, in the early years of the Union Club, membership was capped at 400. After all, according to the scions of the elite, there were only 400 people worth knowing in the city. In 1863, after the club had once again refused to expel its Confederate members, a faction of actual Unionists set up their own breakaway, the Union League Club. (While the first Union League Club was all-white, Reconstruction-era Union League clubs were instrumental in registering freedmen to vote, and the league had Black branches throughout the south.) Other members had opposing concerns: in 1871, the Knickerbocker Club split off from the Union and set up its own headquarters, concerned that its membership standards were too welcoming towards white immigrants: the new club would be solely for members of “New York’s founding families.”

I’m not saying that it was the lack of any minority representation that led the unknown creators of the club sandwich to go in such a frankly bizarre direction, or that fin-de-siecle millionaire WASPs could unhinge their jaws and swallow small animals whole. I’m just saying we should consider the possibility. In any case, the sandwich’s origin is shrouded in mystery. What threadbare stories survive—noted by the likes of Marion H. Neil, author of 1916’s Salads, Sandwiches and Chafing Dishes—feature the typical anonymous-person-stumbles-onto-great-culinary-discovery twaddle. Neil, also the author of “Candies and Bonbons and How to Make Them” and “Canning, Preserving and Pickling,” describes it thus:

“It will not surprise any who know how frequently most excellent things are born of necessity to know that the club sandwich originated through accident. A man, we are told, arrived at his home one night after the family and servants had retired, and being hungry, sought the pantry and the ice chest in search of something to eat. There were remnants of many things in the source of supplies, but no one thing that seemed to be present in sufficient abundance to satisfy his appetite. The man wanted, anyway, some toast. So he toasted a couple of slices of bread. Then he looked for butter, and incidentally something to accompany the toast as a relish. Besides the butter he found mayonnaise, two or three slices of cold broiled bacon, and some pieces of cold chicken. These he put together on a slice of toast, and found, in a tomato, a complement for all the ingredients at hand. Then he capped his composition with a second slice of toast, ate, and was happy. The name club was given to it through its adoption by a club of which the originator was a member. To his friends, also members of the club, he spoke of the sandwich, and they had one made, then and there, at the club, as an experiment, and referred to it afterward as the ‘club sandwich.’ As such, its name went out to other clubs, restaurants, and individuals, and as such it has remained. At least, this is the story as it is generally told.”

“We are told” is generally writer-speak for “I have no proof whatsoever.” Still, the legend of the idiot who made too much toast has persisted for over a century, as has the club sandwich itself. So who am I to quibble? If people want to eat three layers of dry turkey with some wilted lettuce, fine. The Union Club once boasted a humidor with one hundred thousand cigars, so I’m certain the members’ tastebuds were utterly fumigated by longtime tobacco use anyway.

Culinary mediocrity aside, the “club” in “club sandwich” once conferred a certain exclusivity—an air of luxury, or at least privilege. This, we are told (code for: I am speculating wildly), likely has to do with the central role of the social club in early-to-mid-twentieth-century society: central, indispensable, and—at its highest and most desirable echelons—all-white, all-male, and all-Gentile. Jews and Black people made their own clubs. The Harmonie, founded by German Jews in 1871, served as an outlet for the blackballed, and in their 1920s heyday there were several hundred Black social clubs in Chicago, during a time when Harlem’s Cotton Club was rigidly segregated for a white-only clientele.

In the late nineteenth century, the Black women’s club movement was founded, under the auspices of the National Association of Colored Women. By the movement’s peak in 1924, the association’s leagues had some hundred thousand members, primarily in the northeast. In Albany, the Home Social Club “represented the pinnacle of the city’s black social structure”—a forum for speeches about Black advancement and politics, but also a friendly locale for Black men to feast on decadent annual January dinners. 1901’s menu featured “creamed oysters, sherry, roast turkey, suckling pig, peas, asparagus, and mashed potatoes, followed up with mince pie, ice cream, egg nog, fruit, and then “Cigars, Smoke, Talk.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Within marginalized communities, the social club performed the same function as the all-WASP hives honeycombing Manhattan—professional networking, comfort and luxury, good food and good conversation—while also serving the parallel goal of providing a venue for airing ideas about how best to combat oppression. (This was sometimes contentious: Mary Church Terell, the first president of the National Association for Colored Women, pointedly did not invite nationally prominent anti-lynching activist and journalist Ida B. Wells to the organization’s first meeting in 1896, opposed to Wells’ militancy.)

Something that’s been nagging at me as I consider the role of social clubs in earlier American eras is the old Groucho Marx quip: “I don’t want to belong to any club that would have me as a member.” Several variants feature Groucho using the phrase to quit the Friars Club (a raucous comic’s confraternity with branches on both coasts), the Hillcrest Country Club, and—in Groucho’s memoirs—the fictional “Delaney Club.” I’d always taken it as just a self-deprecating quote by a famous wit. I think it still is, but now I’m a bit haunted by the broader possibilities. Did Groucho mean that any club that accepts Jews isn’t worth joining? Either way, it’s funny. Only one way is it the kind of funny that stabs you in the heart with a frilly toothpick.

You might be wondering why I dedicated yet another sandwich column to the history of discrimination and racism in this country, but you must forgive me if I have antisemitism on the brain. It’s been in the news rather a lot lately, and that rarely means anything good in my world. In particular, Kanye West’s ongoing eruption of antisemitic public commentary—telling Alex Jones “I like Hitler,” tweeting out a swastika—has added to an unfortunate history of pitting antisemitism and anti-Black racism against one another in the public eye.

Many have pointed out that Kanye’s similarly outrageous anti-Black comments—telling the world that “slavery was a choice,” or his more recent donning of a White Lives Matter T-shirt—caused him less financial strain than his choice to hang out with Holocaust deniers and spend months ranting about Jews. This is, of course, both true and unfortunate, not least for the antisemitic conspiracy theories about Jewish media control it fuels. But this week’s consideration of the history of social clubs and their sandwiches redoubles my conviction that antisemitism and anti-blackness have always been tightly intertwined, and are best fought together. At the end of the day, we are two populations kept out of the best worst clubs, who chose to make our own. Isn’t that worth something, by way of solidarity?

At any rate, social clubs as a whole began a precipitous and ongoing decline in the last quarter of the twentieth century, succumbing, according to sociologist Robert B. Putnam in his classic book Bowling Alone, to a complex web of social pressures that include suburban sprawl, the nationalization and globalization of the American economy, and the rise of TV. Putnam refutes the idea that the social club died out as a direct result of “white flight”—Black and women’s social clubs died out at similar rates, and overtly segregationist whites didn’t drop out at higher rates. Still, it’s difficult to completely disentangle increasing social atomization from the decades-long national backlash against the civil rights and feminist movements.

The Union Club is still in business, in stately white limestone, as are several of its descendants; but they’re shadows of what they once were in terms of social importance. Their more democratic counterparts—the Rotary Clubs and Elks Clubs and Knights of Columbus that once dotted the country—have largely receded into a more communally-minded past, a fracture only accelerated by the pandemic. Some of this history is one of violent exclusion, to which I say good riddance; other social clubs were bastions of radical and progressive ideas, or just places where people who faced an inordinate amount of shit from a hostile world could get a good meal and have a smoke in a place that was friendly and beautiful and theirs. The club sandwich, though, remains on diner menus from coast to coast, offering in its impractical, segmented construction a kind of totem to a fractious past.

Might be related, "Fine, you 'speak for those who cannot' because you won't let us have a microphone. You finally let us speak, but will you listen? You let us 'have a seat at the table', but are we included in the discussion? You might include us finally, but we still don't feel like we *belong*." --consolidated over the years.

This was highly entertaining, thoughtful, thought provoking and informative. I enjoyed it. I have previously avoided your sandwich essays because the subject sparked no interest for me, but after reading this I will go back and read the rest. Thank you.