Notable Sandwich # 5: Death, Lies, and Baked Beans

The humble baked bean sandwich.

Welcome to the fifth installment of Notable Sandwiches, the series in which I alphabetically work my way through Wikipedia’s sprawling, mammoth List of Sandwiches. I understand that readers may experience some whiplash as this newsletter ferociously alternates between topics (the recent pattern has been: bacon egg and cheese—child abuse—bagels—child abuse—baked beans—child abuse). For me, writing these articles is a way to escape the darkest parts of the human experience; I hope you also appreciate these notes of carb-loaded levity. It’s a way to break free of the news cycle, the brain-numbing discourses concerning the price of milk, and what constitutes rape, and who is feuding with whom on Twitter, the sorts of things that enhance the sense I’ve had lately that every day is drearily melding into the next, an eternal, pandemic-y, inescapable now. But time passes and I move through it, and you do too, towards whatever light or cataclysm awaits us. Today we’re exploring the baked bean sandwich. It is November 5, and tomorrow the sun will rise, and next week there will be a new sandwich. I spent a lot of time reading about the history of beans for this week’s installment, and it was great.

Magic Bean Talk

Let’s get this out of the way first—the part where I explain why I’ve strayed from the task at hand. The baked bean sandwich, the nominal subject of this article, takes a ubiquitous New England staple and sticks it between two slices of bread. The Wikipedia article doesn’t even address the U.K.’s beloved baked beans on toast. There’s literally no meat to this sandwich—it’s just carb/carb/carb—so we’re going to discuss the filling; this is a column about baked beans. Also, while I recognize that a baked bean sandwich is not the world’s most appetizing-looking foodstuff, there is no excuse for this terrifying photo in the article:

So let’s talk about beans and the stories we tell about them.

The moment you get into the business of gathering bean facts—as I have been lately—you run into some fascinating stories that may or may not be true. Beans have been cultivated for as long as humans have been practicing agriculture—according to Beans: A History by Ken Albala, lentils and chickpeas were crucial players in the Neolithic Revolution some twelve thousand years ago, storable sources of necessary protein particularly in the scarce months of early spring. With cultivation came settlement, and with settlement came stories, which sustain us, and which are often larded with gentle, nourishing falsehood.

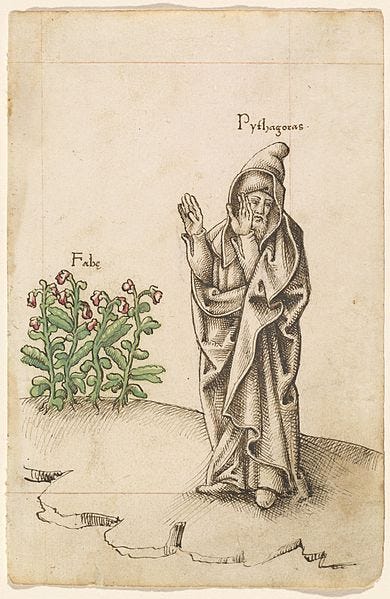

The crown jewel of all bean lore is the story of Pythagoras, the Greek philosopher whose theorem continues to bedevil math students the world over. Pythagoras was by all accounts kind of a freaky dude, one who fled political tyranny to settle with his disciples in a commune in Kroton, on the sole of Italy’s peninsular boot. There, the communards pondered the mysteries of numbers, played guitar, and practiced vegetarianism—an extension of their general doctrine of pacifism. They also refrained, the story goes, from eating beans; this was a strict prohibition, which even precluded passing through fields where beans were cultivated. One version of Pythagoras’ death goes that, while fleeing his myriad enemies, he was foiled by a field of fava beans; refusing to pass through it, he was caught and stabbed by a mob. Other tales say it was his followers who were so entrapped. But why was Pythagoras so anti-bean? Is this entire legend bullshit? And what, across time, can we truly know about the past?

As to the source of the bean prohibition, Aristotle’s favored theory was that, in the Pythagorean worldview, beans were associated with the human soul (proofs: beans smell like semen, bean sprouts look like fetuses.) Other theories regard the flatulence-inspiring qualities of beans as antithetical to the Pythagorean reverence for harmony. By the second century C.E., long after Pythagoras’ death, the Roman essayist Aulus Gellius wrote in his book Noctes Atticae that he interpreted the injunction to be a reference to the testicular shape of the bean, and actually a prohibition against masturbation.

All of which is to say that we leave Pythagoras in the seizures of death against the merciless fava flowers without knowing anything for certain, but abounding with theorems which become as numerous as beans, stranger and sweeter the further we get from him.

Another story, one commonly told, this time about America:

Practically every single history of baked beans you can find on the Internet goes something like this. When European settlers arrived on New England’s rocky shores in the 1600s, they were aided by the ancient and mysterious wisdom of the Indigenous tribes, including the Native habit of baking beans in quaint earthenware vessels with maple syrup and bear fat, creating the antecedent to the sweet, smoky, calorific dish we know today. The European settlers, with their Yankee thrift and indomitable European innovation, swapped in molasses and pork, handing the tradition down over the centuries until, with the advent of modern technology, it became the humble but indispensable canned dish of the present, ready to be sluiced out onto some toast.

This one, I can tell you straight up, is bullshit. Don’t take it from me, take it from Meg Muckenhoupt, who wrote a book literally entitled The Truth About Baked Beans (NYU Press, 2020). Muckenhoupt pored over contemporary sources and came up with some indisputable facts that drive a flint arrowhead through the heart of the sweet stories. The Wampanoag tribes in the region didn’t bake anything at all, really. They lived semi-settled lives along estuaries, and while they did cultivate beans, their consumption was in the form of boiled pottage, upon which any precious sweetness would not be squandered. More to the point, there is absolutely no evidence before 1800 of any baked-bean dishes in the colonial diet—though they may have simply been so common as to be beneath notice, in the way that “very few cookbooks feature recipes for peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.” What’s clear is that by the mid-19th century, baked beans were considered old-fashioned country food for poor folks and tightwads. And that by the turn of the twentieth century they had been transformed, by a syrupy dollop of Victorian bullshit, into a symbol of Yankee virtue.

Muckenhoupt’s book (subtitled An Edible History of New England) is, genuinely, a marvel. I have read a fair number of food books in my time, and The Truth About Baked Beans is a standout: a barbed, witty and meticulous exploration of truths and lies about New England cookery, of which the pot of baked beans is a naggingly persistent highlight.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

The book is centered around one essential thesis: our ideas about what “New England food” means are extremely narrow and inaccurate. This was a deliberate choice by a bunch of stuffy Victorians who were concerned at the erosion of WASP supremacy in the region. Around the centennial celebrations of the U.S. in 1876, these fancy Yankees came down with a case of Colonial fever. They were desperate to shore up the region’s reputation as a repository of the nation’s history, of pure nature, Godly living, and absolutely none of the smelly garlicky immigrants that actually lived in New England. So they plunged the region’s foodways kicking and screaming back into an imagined colonial Eden, and the result has been a century or so of culinary stultification. What was left after the Victorian purge were the items you “know” as New England staples: clam chowder, Maine lobster, apple cider, brown bread, baked beans, and… little else. (If this brazen and sentimentalist myth-making sounds familiar, Thanksgiving was also a Victorian invention, spearheaded by “Godey’s Lady’s Book” author Sarah Josepha Hale.)

Muckenhoupt’s book is chiefly a delicious work of historiography—a story about food that’s really about food stories, and whose purposes they serve. The author wrangles primary sources from journals to cookbooks to archaeological digs into a seamless whole. It’s also funny—Muckenhoupt is so scathing about the New England Kitchen movement, a mid-1800s celebration of colonial nostalgia, that I gasped (“The New England Kitchen movement may have done more to destroy New England cooking than all the graham-cracker-munching, immigrant-loathing, science-quoting Yankee snobs put together”). Other targets include Victorian food scientists (“the root of all culinary misery in New England”) and the moneyed yet hapless matrons of the Boston Cooking School (who “aspired to make what modern middle-class Americans would call ‘toddler food’” and were utterly obsessed with creamed codfish).

At the center of all this immigrant-chiding, colonist-glorifying folly lies the humble baked bean. Beans may have been present in New England cuisine from early on, but the sweet baked bean is a fin-de-siecle invention, as America drowned in cheap molasses and nostalgia (“Why did people start adding so much molasses to beans? It got cheaper, and it seemed like a New England sort of thing to do at a time when Yankee cooks despaired of losing New England to the Irish”). Muckenhoupt created a graph from her analysis of 274 cookbooks from 1880 to 1950 and found a steady, precipitous increase in bean-to-sugar ratio.

As the sweetness proliferated, so did the fabulism, until the legend of benevolent and wise “Native Americans” (not Wampanoag or Penobscot or Iroquois, but just generic “Native Americans”) imparting a dish improved upon by their natural European heirs to the land was firm as dried treacle. That it’s a lie, meant to obscure and sweeten genocide, matters little; it persists. I’ve lived in Boston (well, nearby, just outside Boston, no not Tufts), and baked beans are sort of omnipresent in Bostonian kitsch; every tourist trap sells bean-themed merchandise, and while simmering beanpots are not necessarily tourist-friendly in themselves, you can buy absolutely wretched “Boston baked bean” candy, which I can only describe as like peanut M&Ms, but bereft of both joy and chocolate—like the dishes of the Boston Cooking School, “divorced from human pleasure.” They’re part of a deadening narrative, all tawdriness and Victorian prudery, that has obscured so much for so long.

The ubiquity of the baked-bean myth in pop histories—the way bad sources cannibalize each other, building and building on a rickety myth of the past until it seems secure—contains within it a parable about historiography, how difficult it is to suss out the truth across centuries, and how valuable such excavation is, futile though it may seem. Finding truth amid saccharine falsehood is a difficult thing; our minds are full of stories like this, little tales and factoids based on deliberate misunderstandings and subsequent laziness and motivated mythmaking, and judicious as we might try to be, we will never uncover all of them. We live among them, knowing that, as humans, we have cultivated stories (and beans) for millennia, as spiritually nutritive ways of keeping ourselves going. Most aren’t true—or are half-true—and it is hard, hard work, Muckenhouptian muckraking, to suss out why.

I am thinking, now, about Pythagoras again. I would like to return to him and ask him about the numerology of mystery. I would like to know if he chose death over beans, how he died, what he believed. I never can, but that doesn’t mean truth-seeking is worthless; it’s brave, and hard, and strange, letting the curtain of saccharine bean-steam dispel, and peering clear-eyed into the pot to analyze the murk within.

I've had the phrase, "the business of gathering bean facts" stuck in my head for three days and I'm not even mad about it. Another great article.

This was a deep dive into the history of beans that I did not know I needed. Really, the only flaw I found with it is your disconcerting hatred of Boston Baked Beans (though the description of them made me laugh). I seem to be the only person who actually likes them, so I'm going to assume the company still makes them specifically for me.