Notable Sandwiches #15: Bologna

The quintessential American lunch meat, and the innovations hunger forces on us

This is the latest installment of Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I nibble through the strange and marvelous document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week: a ludicrously depressing essay about the bologna sandwich.

The city of Bologna, in north-central Italy, has an assortment of nicknames, one of which is la grossa, the fat city, for its legendary status as keystone of one of the world’s great cuisines. It’s the birthplace of ragù alla Bolognese, fount of the thick sweet river of balsamic vinegar that flows from nearby Modena, and, most significantly for our purposes, the place of origin, many centuries ago, of the venerable sausage known as mortadella. Mortadella is delicious—larded with pork fat and coriander, pepper and pistachios; it’s supple and yielding, often pressed between the denser bites of soppressata and cappicolo in deli sandwiches—and, in the U.S. at least, its price point reflects a certain level of luxury. It’s a prestigious foodstuff, one you would trot out to impress, arrayed with other delicacies on a charcuterie board. Not so its direct descendant, which took the name of mortadella’s mother city but none of its attendant Roman antiquity and sun-baked grace: the humble and often scorned bologna—or, as I’ll spell it here, in its thoroughly Americanized latter life, baloney.

Baloney is a poor man’s food, or a child’s food—pressed between white bread, indifferently mayonnaised, crammed in a lunchbox to sweat and flop and be bitten into, a pink little puck of nitrates and preservatives. It’s an object of nostalgia or scorn, depending on your vantage point, subject to hipster reclamation and generalized odium. It’s the food of institutions—there have been hunger strikes over the tendency of penny-pinching prison officials to serve bologna sandwiches two and even three times a day to inmates, depriving them of hot meals and rendering their diets themselves a means of punishment. Like most ubiquitous American commodities, the story of baloney is a complex slice of history, marbled with immigration, technological innovation, and, most of all, with desperate privation.

Bologna arrived in America not with Italian, but with German immigrants, who decanted mortadella through their own venerable sausage-making traditions, and by the late nineteenth century had introduced bologna to American cities throughout the Northeast and Upper Midwest. In the 1920s, German and Jewish delicatessens arose to new prominence in tandem with “convenience” apartments that featured tiny kitchenettes for urban workers. As one source put it in A Square Meal: A Culinary History of the Great Depression, by Andrew Coe and Sophie Ziegelman, the kitchenettes were “just large enough to accommodate a carton of potato salad… and eight inches of wienerwurst.”

The proliferation of the deli also meant that cheap, processed meat—and the novel popularity of the sandwiches that enclosed them—attained wide availability just before economic cataclysm overtook the entire country. For the generation that lived through the Great Depression, baloney was a lifeline—households that might once have dined on duck, or veal, or pork loin, were reduced to this sluiced, pulverized, and cured assortment of offcuts, but it might also be the only meat they ate in a week. Or a month. The story of baloney’s rapid spread throughout America is a story of hunger, of reduced circumstances, humbled pride, and an ache in the belly. In Studs Terkel’s masterwork of oral history, Hard Times, which collects the testimony of Depression survivors, Chicago resident Ben Isaacs described what it meant to feed and house his family on $45 of federal aid a month:

I went and found another a cheaper flat, stove heat, for $15 a month. I’m telling you, today a dog wouldn’t live in that type of a place. Such a dirty, filthy, dark place. I couldn’t buy maybe once a week a couple of pounds of meat that was for Saturday. The rest of the days, we had to live on a half a pound of baloney. I would spend a quarter for half a pound of baloney.

The generation that remembers hunger most profoundly in the United States—those who survived the Thirties—long ago began to die, a condition accelerated greatly by the pandemic of the last two years. But some of the children of the Depression live on, and carry with them the habits born of that terrible frugal decade: reusing tinfoil, saving plastic bags, eating in bulk from the freezer, stewing prunes, cooking with offcuts, secreting sugar packets in purses, serving always a spirit of feverish thrift. As one writer put it, observing the habits of his parents and grandparents, these were people “nearly capable of extracting blood from turnips.”

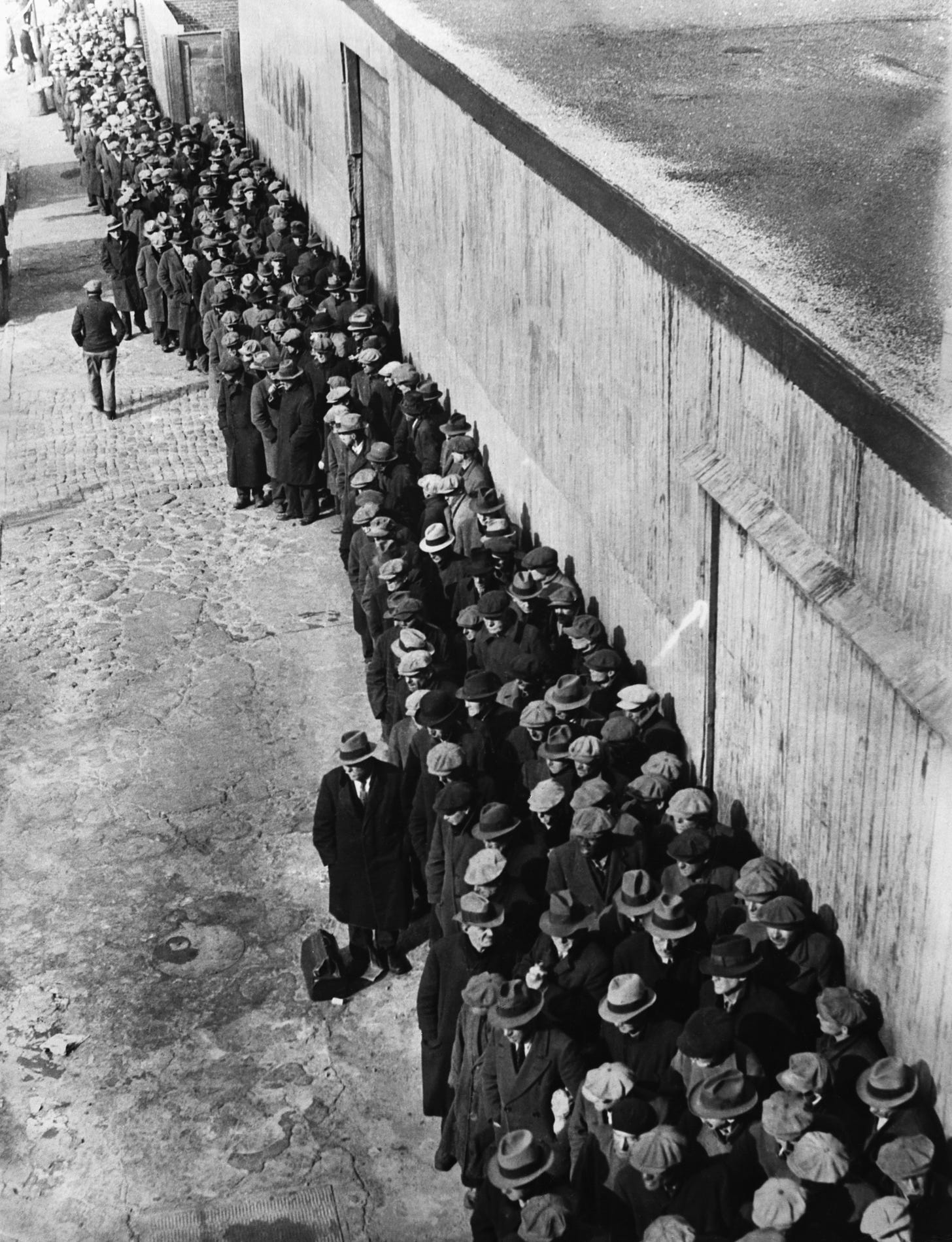

Those were years when people died of hunger in the streets; the most iconic enduring image of the period is the breadline, stretching around city blocks, as people swallowed their pride along with government-rationed salt pork and watery soup. Families that had eaten meat on a daily or near-daily basis went without; families that once had bread made do with potatoes; families that had had no potatoes were left with nothing at all. There were hunger marches in cities across America, and millions more, as Terkel writes, suffered in “private shame.”

When they could, they ate baloney, or ground beef—which attained its ubiquity during the same period, and for the same reason: its cheapness. Then they made baloney sandwiches for their children, who had never gone to bed hungry and woken up hungry; and their children made them for their children, and still do. Baloney gained a warm glow, and its very own Oscar Mayer commercial, rebaptised in the cleansing bath of manufactured nostalgia and commercialism. But it was hunger that brought it to so many tables, hunger that never truly left those who felt it, the lucky ones who lived.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

In the winter of 2013, for a brief week while taking an intensive Ukrainian-language course, I lived in the spare bedroom of a Lviv family, in a stately old apartment building with narrow, creaking stairs that seemed to carry the weight of all the long-warring and hungry past of that city. Three generations of the family lived under one roof in what had been a Soviet collective apartment, with a bedroom hastily cleared for the strange American student. I bought my own food from the multiplicity of tiny markets along Lviv’s winding, cracked and beautiful streets, trudging through the thick snow with unfamiliar verbs whirling through my brain, and my first purchase was a big, pillowy, egg-glazed loaf of bread. I tore pieces off the loaf each night, but by midweek it grown stale in the dry heat of my little corner of the kitchen, and I threw it out. When I returned to the kitchen an hour later, the house’s resident babushka—the kerchiefed grandmother, a silent and forbidding personage who I had glimpsed and greeted but who had avoided, until that point, speaking a single sentence to me—had retrieved the half-loaf from the garbage and wielded it accusingly, pointing it at me like a sword in a hand that trembled.

“This is Ukraine,” she told me. “Here, we do not throw out bread. You can re-use it. You can feed it to the birds. You cannot throw it out. We’ve had hunger here, and we do not throw out bread.”

I took it back, chastened; if she herself had not lived through the Holodomor, the hideous famine of 1932-33 that killed millions in Ukraine, certainly her parents had, or perhaps hadn’t survived it, though she declined to add further detail. And I remembered that my grandfather—who had also spent years in grip of hunger, not too far from this snowy city, on the run from Nazis in the woods—had spent the rest of his life bolting his food, finished in mere seconds with even the most luxurious Sabbath repast, always afraid it might be taken away. Hunger leaves its grooves, its certainties, even in lusher times, the way your bones remember winter on the first cold night in spring.

Peggy Terry, of Oklahoma, told Studs Terkel, years later, that she still felt the scars of the Depression: “You wake up in the morning, and it consciously hits you—it’s just like a big hand that takes your heart and squeezes it—because you don’t know what that day is going to bring: hunger or you don’t know.” Years spent going to bed hungry leaves you hungry even when your stomach is full. It never goes away entirely: a part of you will be hungry forever. You can still see the red rounds of baloney stacked impossibly high for impossibly cheap hanging in the deli fridge in the supermarket, piled up like coins in a hand that needs to count each one—hanging there as they have for a century in the service of keeping hunger, that perpetual unwelcome guest at the table, away.