Notable Sandwiches #20: The British Rail Sandwich

"The Disgrace of England": Less a sandwich than a punchline

Welcome to the latest installment of Notable Sandwiches, where I, in the company of my editor David Swanson, nibble through the baroque and demented document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week: the British Rail sandwich.

As astute readers may have noticed, I have been in quite a depressive rut lately—some combination of my personal circumstances and the broader state of the world, particularly a beloved country being plunged into bloody and grinding war for no good reason. The columns I’ve put out have reflected it—supersaturated with gloom, and I know it.

When I’m depressed, I binge-watch TV—and, even then, pretty much only when I’m really up against it; otherwise I’m made too fidgety by the fundamental passivity of endeavor. Of late, I’ve gravitated towards British shows, mostly Would I Lie To You?, a show about lying, and Only Connect, a quiz show so fiendishly difficult that if I can correctly answer a single question an episode I am overcome with delight. The witticism that the U.K. and the U.S. are “two nations divided by a common language” never rings truer than when I wend my way through baffling cultural references (I am not sure why it would be sinister that someone is a Cornishman, nor did I understand the sheer cultural primacy of Strictly Come Dancing). But this week I, at the very least, had the opportunity to elucidate for myself one long-running British punchline, which has been part of the warp and weft of British humo(u)r for well over a century. All of which is to say that this week, the miasmatic foulness of my mood has run straight up against a sandwich that is not really a sandwich, but more of a punchline: the British Rail sandwich.

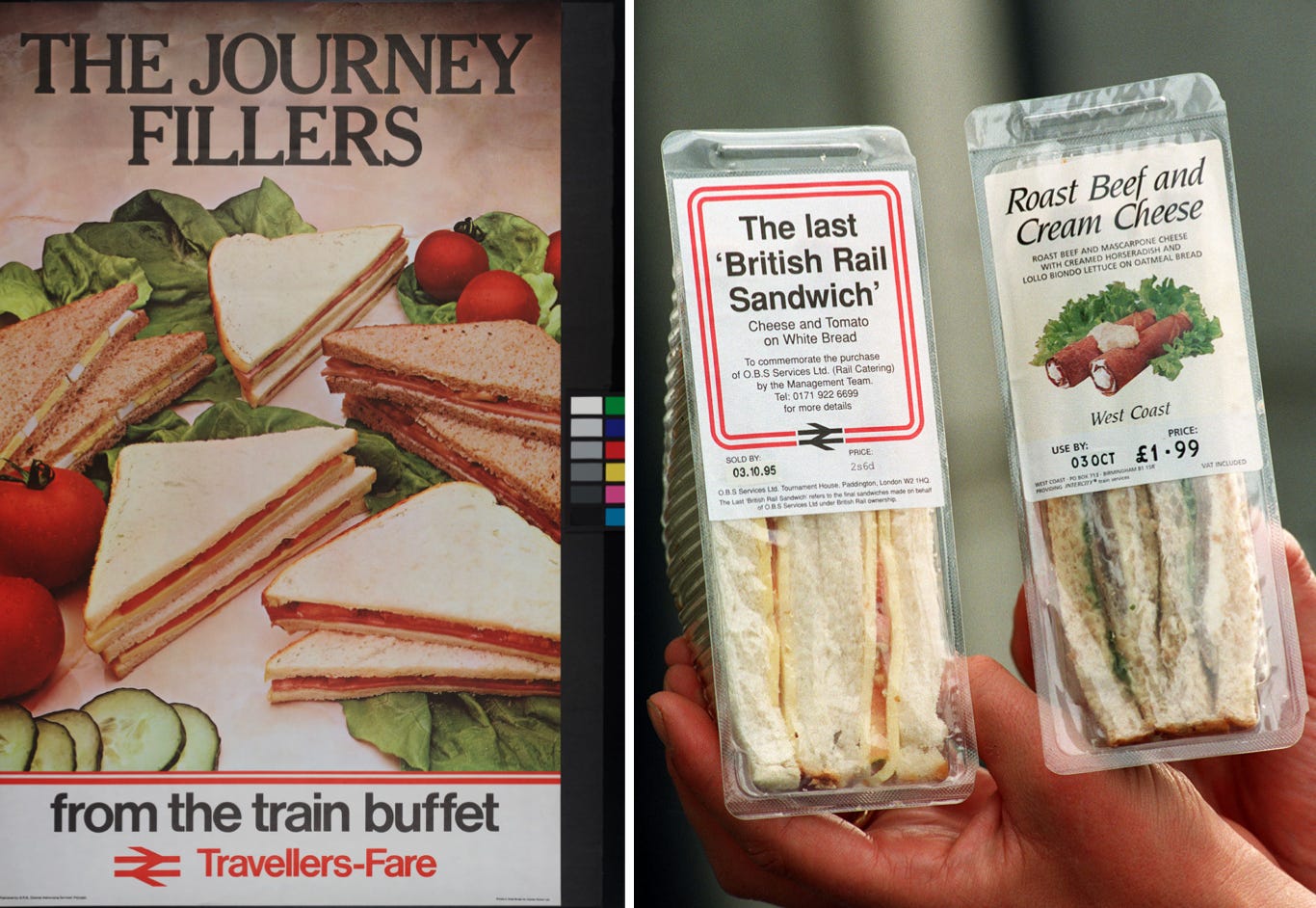

The British Rail sandwich is not really a sandwich at all, but rather a category of sandwiches—modest constructions of hard-boiled egg, cheese and tomato, pressed luncheon meat, tongue, boiled ham, cucumber, prawns, etc., offered on the trains traversing Britain’s many kilometers of railway, particularly (though not exclusively) during the four-and-a-half decades in which it was operated by the her majesty’s government. Nationalized by Clement Attlee’s Labour Party in 1947, and run by a state concern until 1993, British Rail offered cheap, subsidized tickets and cheap, subsidized food to go along with them. These offerings were famously constrained by a set of dictums released in 1971 that gave precise instructions on sandwich construction: no more than half an egg per sandwich, no more than 19 and 2/3 grams of turkey per sandwich, etc. These were Potemkin sandwiches, the fillings artfully arranged to deceive hungry passengers.

A desire for uniformity was perhaps understandable, but the railway sandwich had already been the butt of nearly a century of jokes by Britain’s drollest wags, culminating in a wave of British Rail sandwich humor in the 1970s—a punchline far more ubiquitous than airplane food for U.S. comedians—that paved the way, after the Thatcherite ‘80s, for the eventual dissolution of the British Rail entirely. As the Independent noted about this sea change, “Mrs Thatcher was promoted from retired chemist to Prime Minister. She swept aside James Callaghan, prices and incomes policies and the British Rail sandwich.” Which is rather a lot to lay at the feet of a boiled ham sandwich, even one so bathed in infamy and the smell of crowded trains.

Despite our romantic notion of Victorian rail travel as the height of luxury, poking fun at the middling-to-miserable fare offered aboard the railways has been something of a British occupation just about since the tracks were laid, in the mid-1800s. By 1866, Charles Dickens has a sprightly and devilish lad condemn the “sawdust sangwiches” at a Midlands train station. Three years later, Anthony Trollope called the railway sandwich “the disgrace of England … that whited sepulchre, fair enough outside, but so meagre, poor and spiritless within, such a thing of shreds and parings.” One wit in 1890 proposed that railway sandwiches be used in place of paving-stones.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Seventy years and one railway nationalization later, Good Food Guide author Raymond Postgate was still directing his ire at “the triangular slices of curling bread with a thin slice of luncheon sausage between them, called the Railway Sandwich,” citing them in particular as evidence of the decay of a once-great Empire. The Goon Show, the radio staple from 1951 to 1960 that launched Peter Sellers’ venerable career, had a running gag about the “The Collapse of the British Railway Sandwich System”:

Harry (Cockney): I want to complain about this sandwich. It tastes like muck.

Peter (woman): Muck? Let’s see. Of course. It’s a muck sandwich.

Harry (cockney): Well, I wanted a mustard and cress one.

Peter (woman): Capitalist. I’ll get you one. (surprise) Ohhh! Oh, ‘ere. Someone’s pinched all the mustard and cress out of the sandwiches.

(suspenseful chords)

After I pause for your uproarious laughter, I’ll note that the gag outlived British Rail itself. In 1996, Helen Fielding’s enduring, adorably bumbling Bridget Jones describes herself as having “the personal confidence of a passed-over British rail sandwich” after being rejected by a potential swain. As the commentator Ian Jack pointed out in a rather wistful column for The Guardian, though, all this slagging of the railway and its sandwiches became something of a self-fulfilling prophecy, leading to a cycle of neglect and underinvestment that degraded service and led directly towards privatization.

It’s possible that the lesson of all this withered cress and crusted mustard is to be careful what you wish for. Privatization has been something of a mixed bag in ways that are far too complicated for me to get into (or, frankly, understand well enough to convey here, in the context of a column about a sandwich), but in essence the infrastructure and rolling stock were divided into separate concerns; the infrastructure then privatized; a series of disastrous crashes ensued, after which the network became subject to a wildly complex public-private partnership; the routes were divvied between countless franchisees; and, writes Jack, “any kind of onboard cooking beyond the toaster and microwave is confined to a few trains between London and Swansea or Penzance.” Boris Johnson and Co. are apparently working on a new and shiny public-private endeavor, seeking to overhaul the train system to “maximize efficiency,” and dubbing the effort, which is “simplified but still substantially privatised,” Great British Railways.

Perhaps there will be a new Great British Railways sandwich boom—and with it the inevitable chorus of detractors, once the public good becomes too public. One thing is certain: no matter how miserable the fare, the railroad is a hungry place, and better a sweaty cheese and soggy tomato (or even a sawdust sandwich) than nothing at all on the journey to Swansea.