Notable Sandwiches #56: Denver

Eggs, ham, onions, peppers, and a heavy dose of hokum

Author’s Note: As of this Sunday, I’ll be debuting a new feature, Culture Club, where David & I share the latest stuff we’ve been reading, watching and listening to; hopefully you’ll respond with the same. There might be capsule reviews, rants or raves—expect prolixity! This feature will be available to paid subscribers only, so if you’d like to become part of the Club, click here:

…And now welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, where we trip merrily through the baffling document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week: a Western diner specialty, the Denver omelet sandwich.

Over the course of writing half a hundred essays in this series, I’ve developed a profound skepticism when it comes to the popular origin stories of beloved sandwiches. There’s a certain pattern to them, one that fits the folksy, unpretentious profile of a beloved foodstuff: inevitably, there’s a happy accident involved, some moment of serendipity, a catastrophe turned into inadvertent deliciousness, a strange customer request that turns out to be unexpectedly perfect, and similar.

The great sandwiches are celebrated as burst-forth-from-the-head-of-Zeus creations, cosmic quirks, and not subject to anything so tiresome as premeditation, culinary skill, or market analysis. Inevitably the sandwich pioneer is anonymous—“a housewife,” “a chef,” “a student.” Sometimes specific restaurants are named, and sometimes not, but almost inevitably the whole tale turns out to be the most pungent barefaced bullshit. It makes for good marketing copy, and is all conveniently unverifiable for the most part… but that’s about all I can say to recommend it.

All in all, it’s an irresistible narrative format, recurrent as orphan boys going forth to seek their fortunes, and finding magic in the bargain. It’s been a very long time since I took a literary theory class—and I was lousy at them in any case—but this is what Boudriard might call a mythopoetic form, or classic archetype, a sort of natural groove in the human mind when it comes to telling the tale of a sandwich.

The fact that such tales so often bear a thin, if not actively obfuscatory, relationship to truth is more or less besides the point. It does, however, render the work of your humble sandwich researcher far more difficult. There are so many layers of half-truth to unpeel that it’s tempting to abandon the genesis of any given sandwich as lost to the mists of time. (This is particularly true if I’ve been procrastinating … or if I don’t feel a special connection to a sandwich … or I haven’t hijacked David into embarking on two weeks’ worth of research in three days, as he is so adept at doing.) The Denver omelet sandwich—which is a Denver omelet (diced ham, onion, green bell pepper, egg) on bread—is no exception.

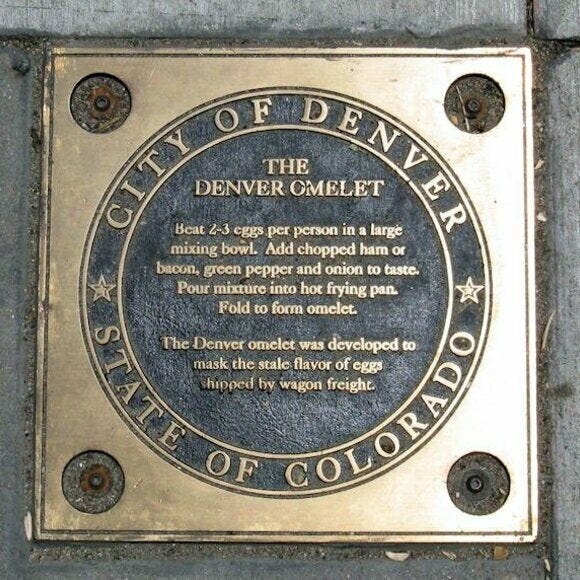

It is, however, one of the few bullshit sandwich-origin stories I’ve seen immortalized on a plaque.

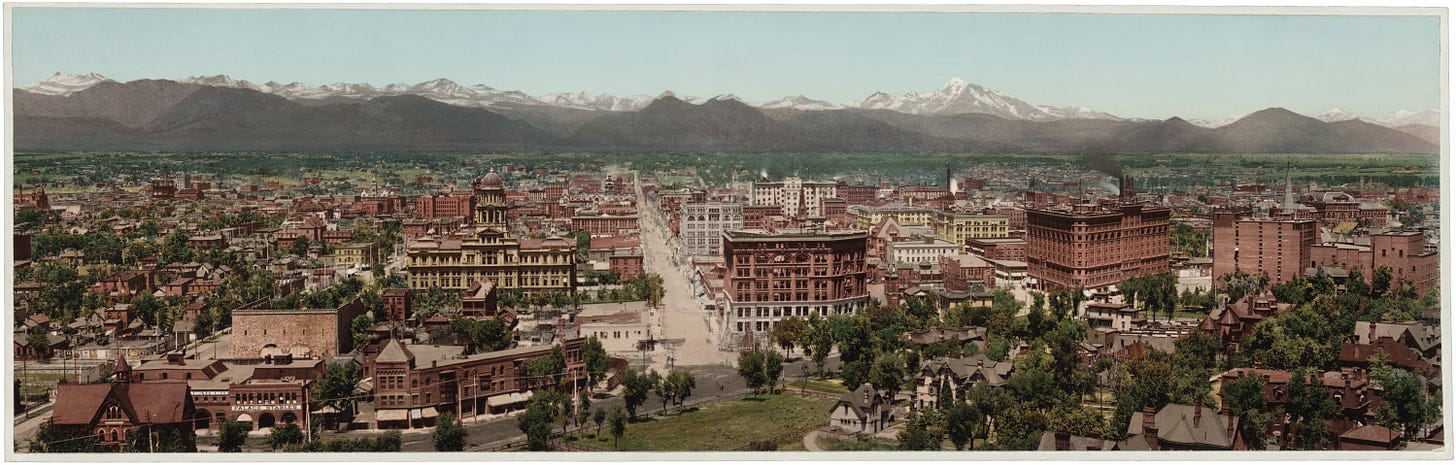

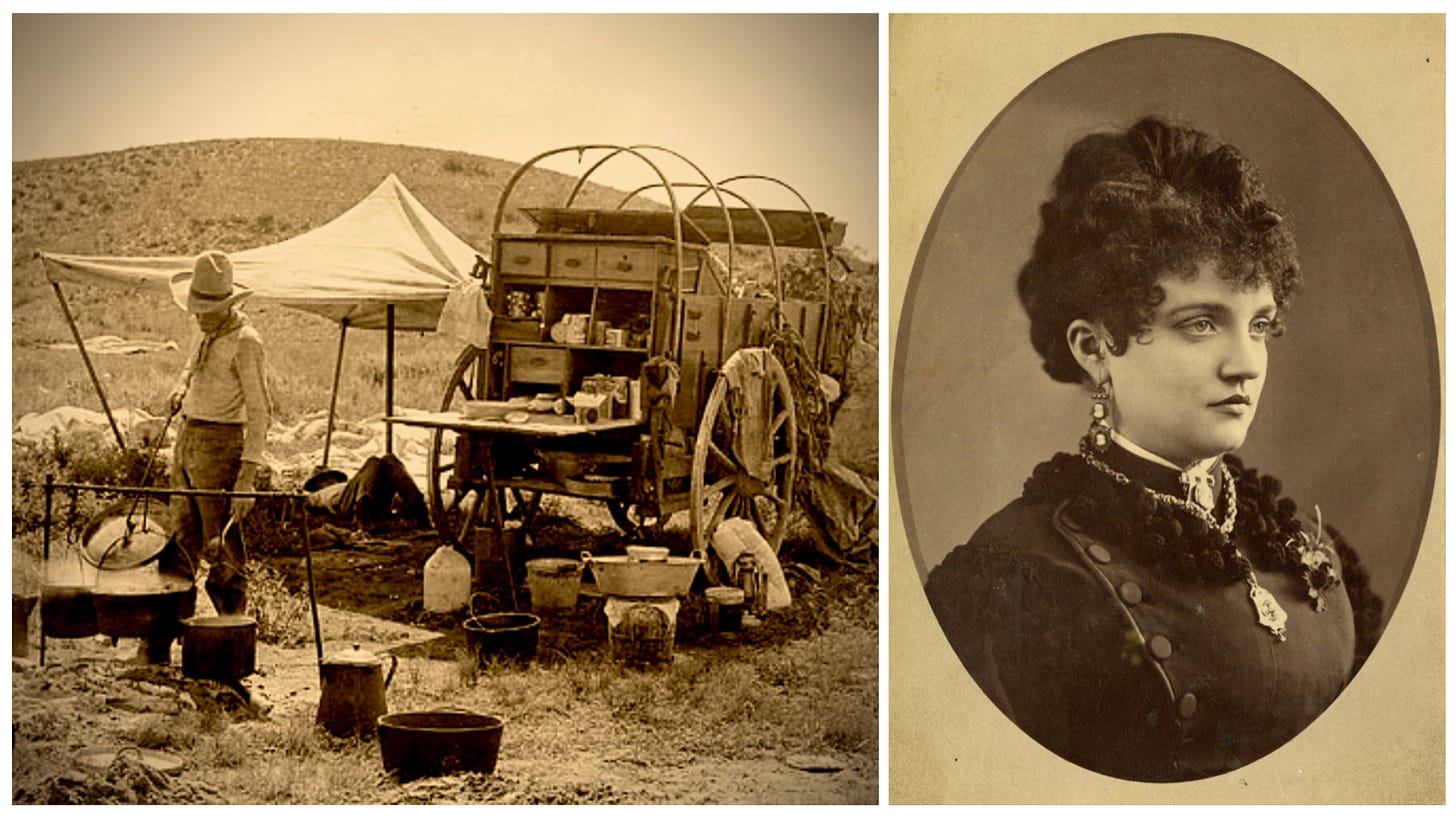

The recipe is a nice touch, and the origin story is somewhat period- appropriate. Denver was, indeed, a center of cross-country wagon-train traffic in the years before the railroad knit our nation together. The memorial on California Street puts a rustic spin on the folk-sandwich-wisdom schtick, evoking pioneer thrift and ingenuity in the face of scarcity. One imagines a bonneted wagoneer wife or hardscrabble homesteader salvaging bad eggs with whatever scraps they could scrape together, stirring the fluffed mass on a skillet over a buffalo-chip campfire, while the prairie grasses whistled and the stars shone out like white lanterns. But the whole thing smells more like bullshit than bacon and onions to me.

For one thing, sweet bell peppers—as opposed to their spicier cousins in the capsicum family—weren’t around in the wagon-train days of Denver’s founding. They were first cultivated in Eastern Europe in the 1920s, according to Balázs Herzog of the Coordination Centre of Fruit and Vegetables Quality Inspection in Budapest. The insatiable Hungarian demand for paprika led to a boom in bell-pepper varietals, a number of which are now officially recognized by the Hungarian state; in 1937, chemist Albert Szent-Györgyi was awarded a Nobel Prize for isolating vitamin C from a peck of red peppers—the most Hungarian of achievements. But all that was nearly a century after pioneering prospectors set up the first shanties at the foot of the Rockies in the hopes of getting rich off gold, inadvertently founding Denver in the process. Wagon-train traffic—which, after the disappointing lack of gold kneecapped the initial settlements, provided the town an early commercial lifeline—peaked in the 1860s, long before the Hungarian pepper merchants had perfected their mellow cultivars.

Even if you accept that some other variety of capsicum was used until the 20th century, the “stale flavor” of eggs is more of a sulfurous miasma—something difficult to mask by dint of mere vegetal distraction. As thrifty as the settlers of the time could be, caught as they were on the cusp between indigenous genocide and nascent civil war, even they would likely have skipped the gaseous eggs and gone straight for the bacon.

And for a third thing, the Denver omelet didn’t even start out as an omelet! It started out as a sandwich. According to local Denver culinary historian and James Beard Award winner Adrian Miller, the Denver Omelet was part of a national egg-sandwich craze that swept the nation in the 1950s; scant references to the dish can be found in newspaper archives before then. Indeed, the dish was primarily referred to as a “Denver sandwich” until the late ‘70s—at which point, somewhat inexplicably, it became far more popular in omelet form, as evinced by the menu at your local diner today.

As to its origins, Miller and other historians have theorized that the sandwich was adopted from Chinese railroad workers, who, while building Denver’s tracks in the late 1860s, may have incorporated a portable version of egg foo yong into their diet. The egg-pork-and-veg combination, handily packaged on bread, would have appealed to even the unadventurous taste buds of early Coloradans.

But as Colorado Life editor Matt Masich has noted, there are even more origin stories from which to choose, each unverifiable in their own way. There are Italian claimants and early-oughts local restaurateurs. There is an apocryphal tale about luminous socialite and tragic heroine Baby Doe Tabor, “the best-dressed woman in the West,” inventing the Denver omelet. This was presumably in her brief interlude of kitchen genius between mining-and husband-related catastrophes (after making, and losing, millions on silver ore, Baby Doe froze to death in a cabin during a blizzard). The factual story may not be forthcoming anytime soon—not without extensive, eggy research, anyway—but the truth of it is almost certainly too messy to fit on a plaque, and likely features neither tragic widows nor plucky frontier heroes.

This is all to the good, perhaps: stories about the pluck and ingenuity of settlers make me itchy; “manifest destiny” is a crock of stale racist eggs; and the state of Colorado was born out of Kansas cracking over slavery anyhow, in a bloody prelude to the Civil War.

The life of a sandwich chronicler is often tiresomely devoted to debunking such snappy myths—stories of sudden inspiration, of anonymous brilliance, of narratively convenient and implausible coincidence. Still, having read enough of them by now to recognize the genre, I can understand their appeal. As hard as it is to turn off my relentless inner skeptic, I recognize that this enduring sandwich myth appeals to that portion of us that feels we are always a moment away from a million-dollar idea. The spontaneously created great sandwich evokes the notion of fate reaching a hand down to touch us with unbidden genius, to grant us immortality between two pieces of bread.