Notable Sandwiches #66: Fish Finger

The ocean is the cold and ferocious mother of all life. And also of fish fingers

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the series where I, alongside my editor David Swanson, trip merrily through the bizarre document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week: the fish finger sandwich.

It’s been a particularly morbid week for those equally fascinated and horrified by the ocean. The story of five men sealed inside an experimental regulation-skirting submersible—men who were mostly filthy stinking rich—getting turned into human gazpacho by the crushing deep of the North Atlantic has gotten the kind of wall-to-wall media coverage that only truly inconsequential stories do. But there’s a certain element of dramatic irony in their intended destination—the wreckage of the Titanic—and the fact that, a hundred years since its initial tragedy, the ship continues to eat the rich. Still more shiveringly horrid is that all this took place down in the dark, where the strange fish, with thick carapaces and spiny profusions and weird light-organs, rule. Where man was never meant to go. The ocean is the cold and ferocious mother of all life.

It also, in roundabout fashion, gave us fish fingers.

The process of making fish fingers (also known as fish sticks in the United States) was initially born out of a vast increase in American seafood consumption during World War II, as beef, the nation’s primary protein, was subject to wartime rationing. Fish-eating dropped precipitously after the war, but thanks to advances in refrigeration, storage and transportation, companies that had adapted to the glut in fishing found themselves with an oceanic bounty—and the technological innovation to sell it.

Speaking of ingenuity: Just like fish and chips, fish sticks were created by a Jew (sorry not sorry for continuing to point this stuff out), the M.I.T. food technologist Aaron Leo Brody. His parents (last name Brozozek; Americanized) fled Poland, he grew up in Boston, and the coup de theatre of his undergraduate work was creating a chewing machine (false teeth hooked up to a mechanism and mounted on velvet) called the Strain Gauge Tenderometer. It’s still on display at the MIT Museum,

While earning his degree in food science/nightmarish denture-machine making, Brody developed the fish stick for frozen-foods giant Birds Eye. As the New York Times reported in 1953:

Quick-frozen precooked fish sticks, introduced yesterday by the Birds Eye division of the General Foods Corporation, may give a much-needed lift to the fishing industry by raising the consumption of fish in this country, according to Herbert N. Stevens, Birds Eye product manager of seafoods. Is said that the new product was considered the most outstanding event in that field of food since the development of the process of quick freezing by his company in the early Nineteen Thirties.

Thanks to the then-novel technique of flash-freezing fish flesh, Brody’s creation was initially marketed as one of those mid-century “Wonders of Industrialization” that would revolutionize the home kitchen with the power of the atomic age, like jell-o salads and microwave dinners. In a lovely 2016 article, Gizmodo author Matt Novak quoted a rather piquant section of a paper called The Ocean’s Hot Dog: The Development of the Fish Stick, by Paul R. Josephson, that describes initial fish-stick harvesters as a kind of frozen, floating tryworks:

Sailors caught, beheaded, skinned, gutted, filleted, and then plate- or block-froze large quantities of cod, pollock, haddock, and other fish—tens of thousands of pounds—and kept them from spoiling in huge freezing units. Once on shore, the subsequent attempt to separate whole pieces of fish from frozen blocks resulted in mangled, unappetizing chunks. Frozen blocks of fish required a series of processes to transform them into a saleable, palatable product. The fish stick came from fish blocks being band-sawed into rectangles roughly three inches long and one inch wide (~7.5 2.5 cm), then breaded and fried.

Delicious! And a definite indicator, even then, of the rapacious overfishing that has depleted ocean stocks to perilous lows. Fish sticks emigrated across the Atlantic to the UK in 1955, where their marketing was less about the awesome power of technology and more about the housewifely convenience of not having to deal with fish bones. Birdseye hit the UK market running with the slogan, “No bones, no waste, no smell, no fuss.” (Little did they know about the band-sawed fish-block situation; as ever under capitalism, no fuss for the end user means that a great deal of fuss has been endured, usually bloodily, far away.) With that sort of pragmatic appeal, it makes sense that the fish finger—and its attendant sandwich, which is just fish fingers inna bun, really—has attained a measure of ubiquity across an island that certainly loves fried foods on bread above most things.

My last big memory of fish sticks coincided with a process I’m engaged in now. Once upon a time, back in the harrowing year of 2020, I was finishing my first book and engaged in the excruciating process of revision. At that point, Culture Warlords was largely finished—I was fact-checking, updating the text to include the fact that a global pandemic had descended since I’d written my first draft, and generally noodling around the edges of my own words, rather than uprooting them entirely. Even so, the process of revisiting one’s own writing can sometimes feel like revisiting, say, the toilet pit dug at a campsite. There may be artifacts of interest in the future, perhaps to archaeologists or bears, but in the present the smell of your own shit is overpowering.

Anyway, I was, among other things, spending my lockdown helping out with childcare for a relative who was then a medical resident at Elmhurst Hospital, one of the hardest-hit public hospitals in Queens, when New York City was an epicenter of covid deaths and the whole city was a siren-ridden ghost town. Everything was so upturned and unnerving, and there I was finishing a book, as if there were any guarantee that books would still exist in a few months, everything felt that imperiled. But we had to cook for the kids and eat with the kids and make sure they ate and that they were okay, a responsibility that never ebbs for the duration of the time you are around little kids. And one of the ways to do that was to make a lot—an awful lot —of fish fingers. Cheap, bland, fried, palatable protein was a godsend, and if the flavor reminded me of similar meals in my own childhood, so much the better: an anchor in an apocalypse.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

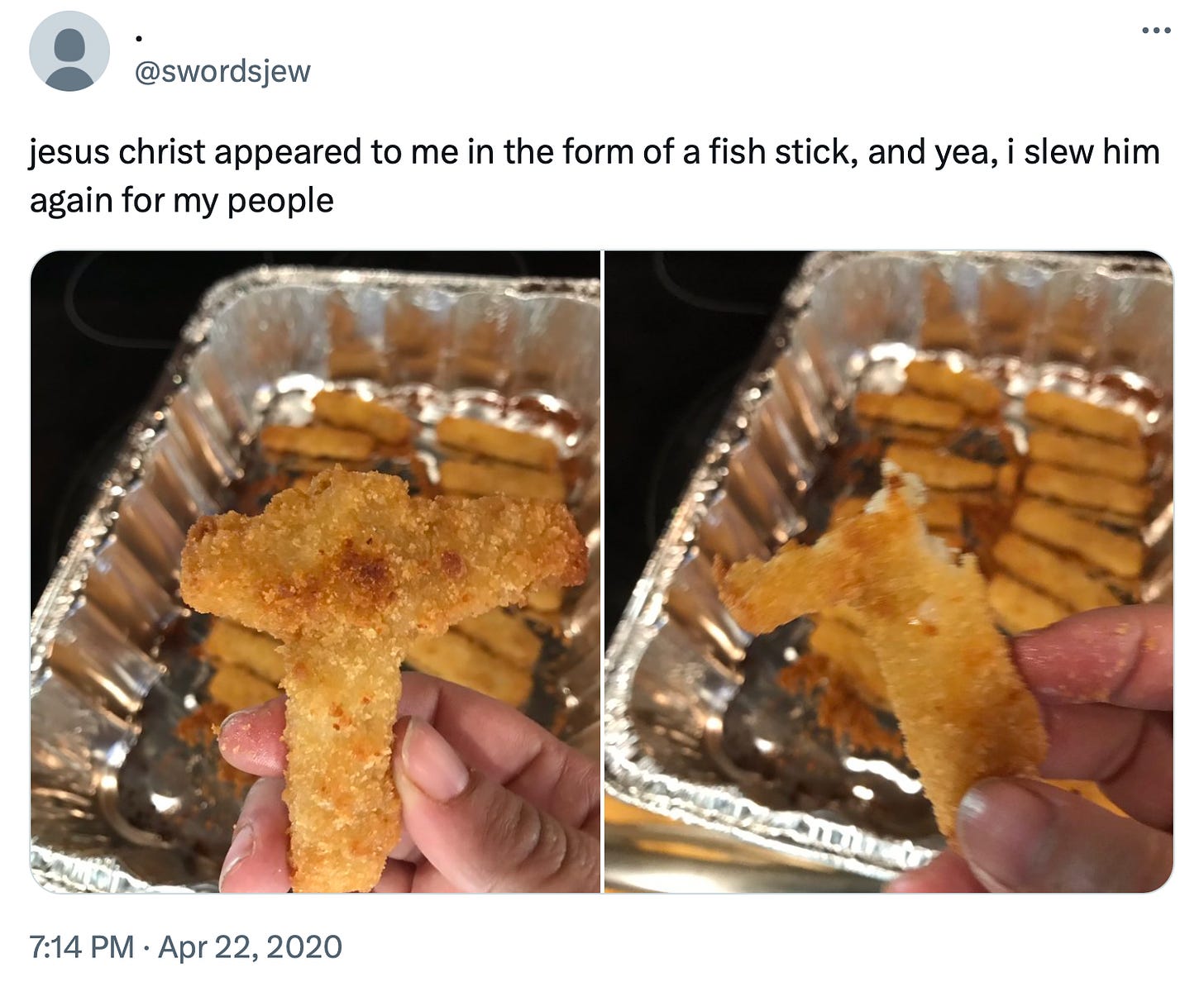

My first book was about hate—the rather straightforward neo-Nazi kind, which proudly self-labels as such—and while it was tough and abrasive and frankly a bit traumatic to spend all that time immersed in absolutely poisonous rhetoric, there was at the very least a sense that I was doing my squirrely book-writer’s best to fight evil. This also meant that I was occasionally inspired to poke it in the eye. During one of my nightly prep sessions for the kiddos, I found myself with two fish sticks that had fused in the shape of a cross. In a mordant mood—and absolutely spoiling to rile up the masses of Christo-fascist antisemites that trawl my mentions like cod fishermen—I posted a picture with a caption about slaying Jesus all over again. It’s a very old antisemitic canard that we did so in the first place, and I was dangling bait for some of the dumbest and most vindictive people around. Did they go insane? Absolutely. Did I eat the fish stick cross, and was it delicious? Also, yes.

My current book is also about hate, more or less, and I’m currently engaged in an even more tormented process of revision, in which the world is (somewhat) more settled, but I’m infinitely not. I’ve been cycling between near-catatonia and vibrating, neurotic spasm, an enfant terrible of moodiness and sheer resistance to work (a lassitude I sometimes call Bartlebyism). Part of what impels you through a first book is the sheer terror and power of the feeling that you are writing a damn book, your name will be on a book as you’ve dreamed of your whole life! In a sophomore effort you’re shouldering the weight of expectation, trying to surpass the initial book’s literary quality and sales quantity, all the while attempting desperately to whittle out something to say about the fetid, bubbling cesspool of American life.

Moreover, this particular book is quite substantially about right-wing Christian fundamentalism, and by extension all the evil men do in the name of the man whose symbol I so crassly devoured. There have been quite a lot of feelings to sort through in the making and remaking of this work—the ways in which I have contended with so much soft Christian antisemitism and overt Christian antisemitism in my life; what it means to be a member of a minority faith in an age of increasingly strident and open Christian theocracy in the US; how to disentangle that rage from the text and deconstruct it on the page; and just how I angry I am at all the people who want to subsume me body and soul into the fiery cross they dream of burning into the flesh of this country.

It feels frightening to write about at this moment, a lesson written out in the blood of my forebears, even the inventor of the fish stick. There’s a reason you flee Poland, a reason you change your name from Brozozek to Brody, a reason you hide, a reason you make nice, don’t post a dumb tweet about fish sticks and Jesus. Even if you’re a punch-happy idiot like me, the rough skin of the circling sharks rasps at your flesh. I have buried these emotions for so long that trying to access or neutralize them feels like reaching into a crushing depth, a place of tortuous inner compression.

Whatever type of Jew I am, it’s certainly more the sensitive and/or lackadaisical poet then the brilliant man of science; I am no Aaron Brody. Lacking the sort of practical mind that can respond to this existential neap tide by sending out a trawler equipped with flash-freezing and breading equipment, I can only try to tread water, catch a ride on any floating debris, cut my feet on reefs until it ebbs. I need an inner anchor to tranquility, something as bland and good as the taste of fish fingers. In lieu, I’ll keep sounding the depths, listening for the skittery fins of the strange life that skirls down below where the sun ever reaches, where no man ever should swim.

Brilliant writing, thank you!

And now, as is so often the case when you mention a sandwich popular in my country of origin, I have a ridiculous hankering for a fish finger butty, which I haven't had in decades!

omg fish sticks! growing up in a very large Irish Catholic family back in the late 50s and 60s, there of course was the perennial Friday ‘no meat’ thing - now, there was no way my mum was going to make a veggie dinner on Fridays, she only did the odd salad and maybe some peas or lima beans as a side to our usual meat-based dinners - so it simply had to be fish, and since she had no clue whatsoever about cooking fresh fish it had to be fish sticks - every Friday for years, then: fish sticks! they were so amazingly easy to make (take out of the freezer and pop in the oven, no prep needed) - I don’t know if this childhood was why I ended up working for an international sustainable fishing NGO, spending years on and around fishing boats and fishermen, and not eating any meat, but who knows?