Notable Sandwiches #70: Fricasse

"It takes a lot of history to make the world’s most perfect sandwich"

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, alongside my editor David Swanson, trip merrily through the strange and mutable document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, a Tunisian delicacy by way of southern France and colonial conquest: the Fricasse.

This is the threescore and tenth essay in our series about sandwiches — a vast buffet that’s so far spanned from Scandinavia to China to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and we’re only up to the F’s. Over this span I have sought to hold my fire when it comes to discussing relative deliciousness; I try to tend to the history of the sandwich, and the people and countries it evolved out of and sustained. Each sandwich has its own story, whether that’s just the life of one ambitious cook or darker, stranger, wider currents, hardly able to be contained in two slices of bread.

In discussing the Tunisian fricasse, however, I feel compelled to drop my guard, although the history of this sandwich is at least as intricate — and certainly as bloody — as the darkest entree on the list. This is because it sounds to me like the most delicious sandwich in the world. It hits at my taste buds so strongly I am held in thrall. It has everything I want to eat in one fried bun, a perfect little sally into the stomach. At heart, it is a southern French pan bagnat — a salade niçoise on bread: flaky tuna, hard-boiled eggs, olives. The journey over the water — 833 kilometers as the crow flies from Nice — transformed it, added harissa, preserved lemon, and changed the dough from baguette to a simple split fritter. A pan bagnat is already a lovely thing — I have eaten them when I was in my heart’s first love and loved them as I loved him and life at that time — but it took conquest to perfect it, empire to bring out its true sharp spice, the tang that should have been there all along.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

I condemn empires and all those who build them or seek them, including the one I live in; don’t mistake my culinary enthusiasm for colonial nostalgia. It’s a sidelong irony of fate that a history as grand and complicated as the near-century of subjugation imposed by the French on Northern Africa is what it took to perfect a sandwich, and the fricasse is a luminous footnote in a much longer and sadder tale.

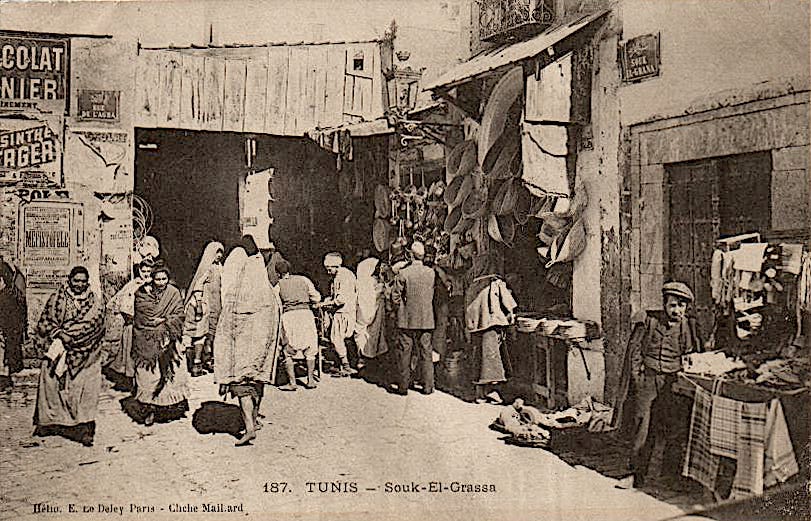

The French conquest of Tunisia was, as conquests go, a stroll: the casual exercise of power without excessive bloodshed. In essence it was a gentleman’s agreement, though the Tunisians were not consulted; Europe had been nibbling at its debts and finding the country ripe for conquest for a long time before it happened. Italy and France and Britain were competing parties — Italy took over Tunisia’s railroads, for example — but a handshake over a table in the capital of Germany sealed the country’s fate, in absentia.

The path for Tunisia to become a French protectorate was smoothed during the Congress of Berlin, in the summer of 1878, a meeting between the great powers of Europe — the United Kingdom, Russia, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, France, the Ottoman Empire — in the immediate aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War. It was one of those meetings in which small men in big rooms decide the fate of millions, shuffling national borders and identities in a matter of days.

The principal goal of the Congress was to decide the fate of the Balkans — and not incidentally set Europe on a precipitous slide towards World War I — but ceding Tunisia to the French, without Tunisian representation or consent, was an offhand byproduct of the meeting; it was an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire, and the Ottoman Empire had lost the war. Tunisia was a sixty-three thousand square mile afterthought — an afterthought with humid coastal plains and the ruins of Carthage and a constitution in which Muslim, Christian and Jewish inhabitants were to be treated as equal. In chess terms it was a pawn in the paw of the power across the sea, on the green-and-blue chessboard of the world that the small men in the big room had carved into neat little squares for occupation.

In 1881, after buying up a goodly portion of Tunisia’s substantial debts, the French sent a military force into the country, nominally to put down a tribal rebellion. This invasion culminated in the Treaty of Bardo, signed in the court where the Beys of Tunis had ruled for centuries. According to the treaty, this occupation was nominally temporary. In the end it lasted until 1956, following years of assassination and massacre that culminated in Tunisian independence.

Occupation and subjection jar loose, in their violence, pieces of culture that lodge themselves in unlikely places. Among them was the pan bagnat of Nice: the sandwich took a long trip to Tunis and was adopted, beloved, changed. Tunisia has a long coast on the Mediterranean where tuna swim, big carnivorous beasts that perform long and mysterious migrations. Pressed into a fricasse alongside boiled egg and olives, potatoes and harissa and pickled lemon, the fish’s flesh is perfect, hot and salty and filling and fine.

Harissa — the chile paste that is ubiquitous in North Africa — is another product of empire, a circuitous one: in the 1500s the Spanish conquered and held Ottoman Tunisia for a time. Their world-straddling ambitions had already encompassed the New World, where chile peppers originate, and from that time — likely in Tunisia, which gets the credit for inventing harissa in UNESCO’s books — Maghrebians pounded the peppers and mixed them with olive oil and citrus and garlic and salt and spice. Three hundred years later harissa migrated into a French sandwich in a fiery red bloom and stayed.

There are two Tunisian takes on the pan bagnat of Southern France. The first and easiest to obtain is the Casse-Croûte Tunisien, which I have eaten many times in New York City: it is essentially a pan bagnat with harissa added, served on a baguette.

The Jews of Tunisia took this idea and fried it and made the fricasse. There have been Jews in Tunisia for a very long time, but it was supposedly not long after the French conquest that a Jewish woman, facing a surplus of fried buns and a lack of sugar, decided to fill them with the regional spiced-up niçoise. While oral culinary history is often dubious — and inevitably takes the form of some fortuitous coincidence — the notion that the fricasse has Jewish origins is durable enough that it’s stuck around since the 1800s; supporting this, you can find fricasse wherever North African Jews have migrated, particularly in Israel. It seems like every time a fried fish sandwich has come up on this list a Jew invented it. Maybe we just like ports, or oil, or both; maybe it’s no coincidence that a fricasse is a two-bite portable version, sold from carts, or booths, or a ready provision if you have to run. It is a very simple dough — yeast, water, flour — and all its savor is granted by that fantastic collection of ingredients inside, tart, spice, savor, freshness, starch, fat. I cannot even think about this sandwich without salivating; my stomach rumbles like thunder over the sea.

Every sandwich is in its way a piece of the long strange detritus of history, even if it is just the story of one life, and not a country or a continent or a struggle for power that lasted most of a century. It’s part of the story that made humans start growing wheat and pounding it, mixing it with water and waiting for the air to yield the mysterious agents that make dough rise, and calling it bread. Seas and violence and the worship of different gods and money and fire and power are all parts of that story, one culmination of which is the fricasse. It takes a lot of history to make the world’s most perfect sandwich, a jumble of unlikely jostlings of greed, fate, and hunger. That it is the product of conquest and reconquest, of migration and cross-continental innovation, of Jews surviving slinging fish on the hot streets of Tunis, adds piquancy to its savor and does not destroy it. I want to sink into it teeth-first and never come out again.

yessss I actually added this to the Wikipedia list months ago so I could get an essay on the sandwich which kept me going through lockdowns in Israel, fantastic essay! the place I frequented adds a brik in middle for even more indulgent fried goodness

This is a great essay. You write beautifully.