Notable Sandwiches #72: The Gatsby

An elephantine icon, created under the unnatural weight of apartheid in South Africa

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, alongside my editor David Swanson, trip merrily through the bizarre and mutable document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, a Cape Town street food staple: the Gatsby.

In 1976, in one of the most violent years of the apartheid era in South Africa, a man invented a sandwich.

His name was Rashaad Pandy, the proprietor of a small restaurant called Super Fisheries in Athlone, a suburb of Cape Town in the sandy and windswept area known as the Cape Flats. The occasion of the Gatsby’s invention was intimately intertwined with the upheavals the apartheid regime forced on nonwhite South Africans. Pandy was designated as an “Indian” under the nation’s racial classifications, which divided the South African population into Whites, Indians, Coloureds (people whose racial makeup which did not neatly map into the intricate and absurd scientific racism that dictated apartheid) and Blacks. Under the Group Areas Act of 1950, the government sought to eliminated mixed-race neighborhoods, and to designate specific areas where racially-determined categories would live, segregated from one another. Between 1960 and 1983, around 3.5 million South Africans were forcibly removed under these laws. Pandy was one of them.

Pandy had grown up in the Cape Town suburb of Claremont; under the caprices of the Group Areas Act and its successors, he and his family had been forced to relocate, a few kilometers and a color line away. In 1976, Pandy offered to feed some local workers who had cleared a plot of land for him in the new racially designated area of Lansdowne. Pressed for time, he rushed to his shop and slapped together a cheap but filling meal out of ingredients readily available in his shop: an entire loaf of Portuguese bread, French fries, poloney (a cheap, bologna-like sausage), and Indian atchar pickles. He cut it into wedges, and one of the laborers pronounced it “a Gatsby smash”—a reference to the 1974 film adaptation of The Great Gatsby, starring Robert Redford, which had been showing in a nearby cinema. A Cape Town legend was born, and Pandy is still serving it long after the fall of apartheid, 250 to 300 Gatsbys a day. The enormous sandwich can easily be portioned out among four diners, or saved for multiple meals.

For years, the white-led government had tried, unsuccessfully, to stem the tide of native workers seeking employment in South Africa’s cities. Ultimately, they attempted to shunt millions of Africans into artificially created “reserves” (under apartheid, the reserves were reconfigured as “Homelands”) that served as little more than overcrowded enclaves bereft of public services. Education was severely limited, extreme poverty omnipresent. Lack of education and poverty among the Black population were then treated as pretexts for treating them as “barbarous” and incapable, the monstrous tautology of the state. Treating people as animals—limiting their movement and opportunities and retaliating to any deviation with brutal violence—is the predatory, circular logic that gave birth to apartheid.

From the 1940s onward, Black “squatter” movements had risen in resistance to the enforced confinement of the Black population into squalid rural enclaves. Squatting was an act of survival: in the reserves and, later, the Homelands, hunger was so common that children routinely suffered from kwashiorkor, a disease of extreme malnutrition that causes grotesquely distended abdomens; many died before the age of four. Oriel Monongoaha, a leader of a squatter camp that would go on to become the million-strong settlement of Soweto outside Johannesburg, emphasized the nimbleness and ingenuity of the squatters as opposed to the crude and clumsy forces of the state. “The government was like a man who has a cornfield which is invaded by birds,” he said in the ‘40s. “He chases the birds from one part of the field and they alight in another part.”

Unable to contain Black workers—and compelled by the need of whites for cheap and exploitable black labor—authorities herded them into distant shantytowns. They also enforced a “pass” system in which Black workers had to present official documents on the threat of imprisonment or expulsion—a fate that befell hundreds of thousands of Black South Africans. And even with a pass, they were unable to use public or private facilities freely. Under apartheid, as the historian Leonard Thompson noted in his seminal A History of South Africa, “Laws and regulations confirmed or imposed segregation for taxis, ambulances, buses, trains, elevators, benches, lavatories, parks, church halls, town halls, cinemas, theaters, cafes, restaurants, and hotels, as well as schools and universities.”

By the 1970s, one work-around to meet workers’ needs arose in the form of businesses created by Indian and Coloured South Africans, whose foothold in the nation’s racial hierarchy was a liminal one; placed above their Black countrymen, but below the white ruling class, they lived at the fringes of the city. Their situation has been described by the Indian-South African writer Youlendree Appasamy as that of “the middleman minority, with an immediate relation to the indigenous population as buyer and seller, renter and landlord, client and professional.” In this context—of proximity and distance, relative privilege and concomitant insecurity—halal take-aways blossomed.

The scholar and artist Tazneem Wentzel wrote her master’s thesis about the Gatsby and another sandwich, the Wembley Whopper, both Cape Flats innovations that coincided with a renewed period of resistance to apartheid. “The popularization of take-aways occurred alongside increased political consciousness and activity in the area,” she explains. “The Gatsby catered to the palette and the pocket of the black consumer that was in a constant state of mobility between home and work.” In the aftermath of forced removals, these establishments became sites of resilience and agency in the face of precarity, Wentzel contends.

“Apartheid was massively unjust, but it was also massively inefficient,” explained University of Tennessee assistant history professor Carolyn Holmes, author of The Black and White Rainbow: Reconciliation, Opposition and Nation-Building in Democratic South Africa, in an interview this week. “Private industry and these chefs and people stepped in to try to make up for that, with these portable meals.” The city of Durban’s answer to the Gatsby, Holmes points out, is the bunny chow, a massive proto-sandwich consisting of a hollowed-out heel of bread filled with curried mutton or beans; like the Gatsby, it provided cheap and handy sustenance for laborers forced into the perpetual motion of long and arduous commutes from racially designated living areas to the center cities where their white employers lived.

Apartheid was not simply unjust, or inefficient. It was also, Holmes contends, “deeply weird” and profoundly obsessive: a fixation on race science that became increasingly outmoded as the decades wore on; the limitation of movement; the freakish artificiality of the Bantustan “Homelands” it created; and the hysterical fear of any commingling that permeated every aspect of South African society for fifty long, repressive years. Apartheid’s project—to contain and subjugate the natural movements of populations, to reduce most to migratory labor to be exploited, and at the same time elevate a minority into absolute rulers—contained in its own unnatural nature the seeds of its eventual destruction.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

“Existentially and culturally, separating people was their goal,” Holmes told me, and limitations on who could eat whose food, and where, and when, were an intimate and daily component of that intrusion. “Making people carry home a loaf of bread full of curried beans because they had to be kept culturally separate—that’s a wild ambition to even have. It’s wild to even think that would be possible.”

Trevor Noah, in his memoir Born A Crime, describes the absurdity endemic to apartheid in an anecdote about his Swiss father’s attempt to open an integrated steakhouse in Johannesburg, under a legal loophole designed for visiting black travelers and diplomats. The restaurant was a booming success, allowing Black South Africans a rare opportunity to dine at an upscale establishment, and creating a rare locus of intimacy for whites whose lives were sealed off from their racially distinct countrymen. Noah writes,

The curiosity of being together overwhelmed the animosity keeping people apart. The place had a great vibe. The restaurant closed only because a few people in the neighborhood took it upon themselves to complain. They filed petitions, and the government started looking for ways to shut my dad down. At first the inspectors came and tried to get him on cleanliness and health-code violations. Clearly they had never heard of the Swiss. That failed dismally. Then they decided to go after him by imposing additional and arbitrary restrictions.

“Since you've got the license you can keep the restaurant open,” they said, “but you'll need to have separate toilets for every racial category. You'll need white toilets, black toilets, colored toilets, and Indian toilets.”

“But then it will be a whole restaurant of nothing but toilets.”

“Well, if you don't want to do that, your other option is to make it a normal restaurant and only serve whites.”

He closed the restaurant.

A national life of artificially imposed separations, of labor migrations and prohibitions, of repression and torture, is nothing but toilets as far as the eye can see.

In the 1960s—a decade of peaceful efforts having been ignored and then extinguished by the state—young anti-apartheid activists resorted to a campaign of bomb attacks on post offices, government buildings, and railroad installations. The state’s response was crushing. “By the end of 1964, the first phase of violent resistance was over, and for another decade the country was quiescent,” Johnson writes. Nelson Mandela and other activists such as Walter Sisulu and Govan Mbeki, the father of future South African president Thabo Mbeki, had been sentenced to life imprisonment. However, as Johnson further notes, “Quiescence did not mean acquiescence.”

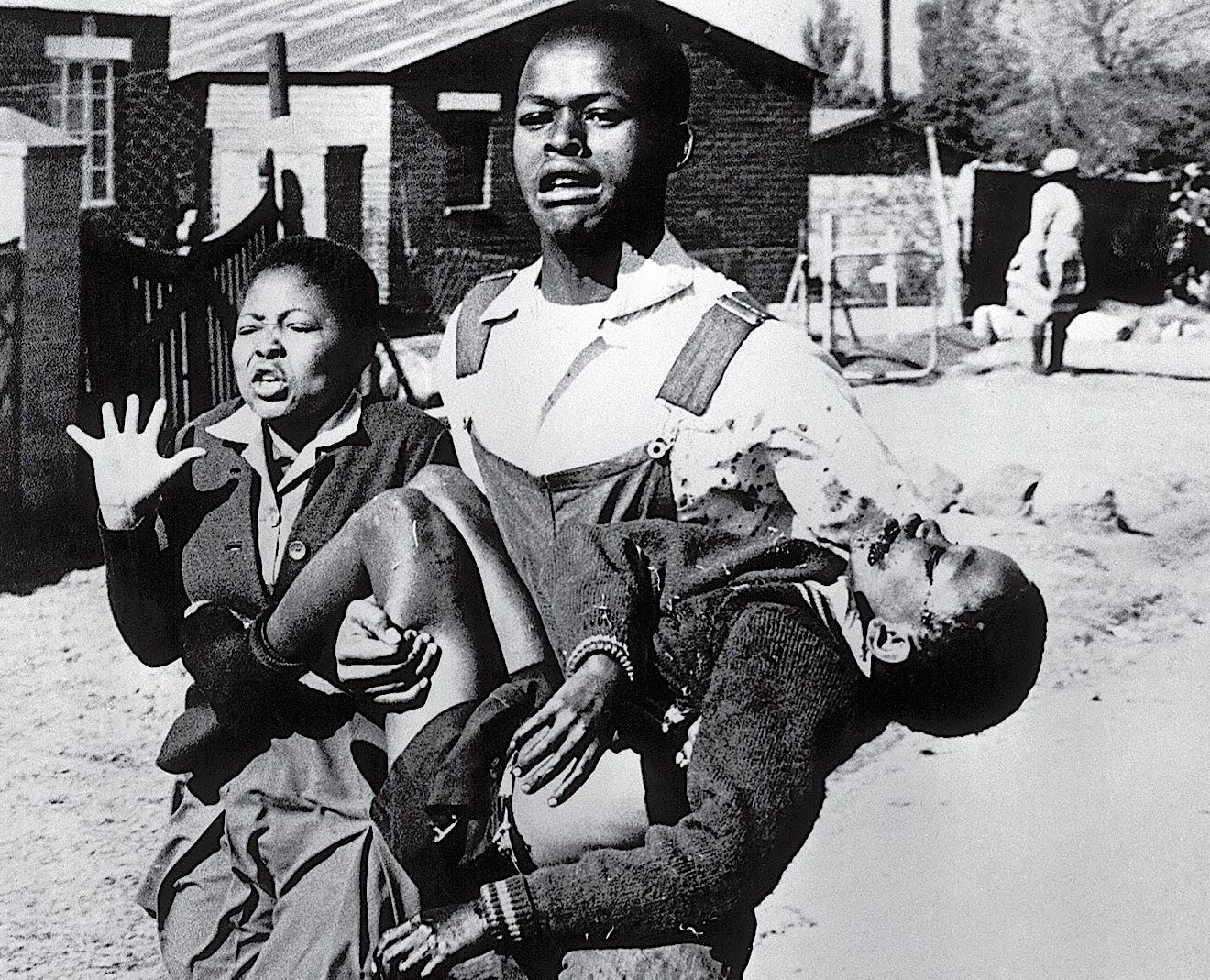

1976, the year of the Gatsby, was also the year in which students in South Africa rose up after over a decade of relative dormancy. The occasion was a new law that forced Black students, in their segregated schools, to receive their education in Afrikaans. Not only was this the language of their oppressors—Boers convinced that their racism was endorsed by God, nationalism, and science alike—but the laws were a crippling blow to the Black students’ ability to learn. Never having been taught Afrikaans, they were now expected to learn mathematics and other subjects with Afrikaans as the language of instruction: an impossibility, and an indignity. On June 16, 1976, students marched en masse in Soweto—where they were killed in great numbers.

A photo of 12-year-old Hector Pieterson, a Black boy who had joined the Soweto march and been shot to death by police, galvanized student protests around the country. 92 people were slaughtered in the Cape Town area alone; by February 1977, at least 575 people had been killed. The uprisings of 1976 ended in tragedy—134 children under the age of eighteen were among the dead—but also anticipated apartheid’s downfall. The images of police shooting unarmed and peacefully protesting students went a long way towards isolating the apartheid regime on the world stage.

Resistance to apartheid, both violent and nonviolent, contributed to the fraying of an unnatural and dehumanizing framework for human life, one that separated populaces according to ludicrous tests, (“South Africa had a crazy system of deciding your race, including whether the moons of your fingernails were a bit more mauve than white, indicating a hint of black blood. There also was the test of whether a pencil would stay in your hair, indicating it must be of kinky black stock,” wrote the journalist Michelle Faul, recounting life under apartheid) and enforced the absurdity with brutality.

A sandwich column may seem like an unlikely vector for a history lesson about apartheid, but food is sneaky that way, interleaving our lives so subtly as to be present in every great and sordid moment of human history. In his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, Nelson Mandela describes having to leave a safe house in a white area while on the run from the government in the ‘60s because of his penchant for the Xhosa food he grew up with.

“While I was reading in the flat during the day, I would often place a pint of milk on the windowsill to allow it to ferment,” he wrote. “I am very fond of this sour milk, which is known as amasi among the Xhosa people and is greatly prized… It is very simple to make and merely involves letting the milk stand in the open air and curdle.” After overhearing two Zulu men commenting on the amasi curdling on the sill, Mandela worried that his cover was blown. “The sharp-eyed fellow was suggesting that only a black man would place milk on the ledge like that and what was a black man doing living in a white area?” he wrote. “I realized then that I needed to move on. I left for a different hideout the next night.” A bird alighting from the cornfield.

In this time of upheaval, the Gatsby played its role, not just in feeding hungry workers forced to trek arbitrary lengths for low-paying jobs, but in contributing to the activism that surged through the Cape Flats in the years after its invention. “Often, Super Fisheries kept their kitchen open till late on request from rally organisers to feed the hungry masses after their political activities,” Wentzel writes, recounting her interviews with Pandy.

It took blood to fell apartheid, but it truly ended in politics, in the historic 1994 vote that, for the first time in South Africa’s history, saw an electorate and a slate of candidates not restricted by the color of their skin, the ability of their hair to withstand a pencil, or the width of their noses. Mandela was elected President. The vast and petty cruelties of apartheid, its unnatural repressions and constant humiliations, were dismantled one by one, though their legacy still lingers. The restaurants were open now to any who could eat. But the Gatsby had always been available to anyone who approached the counter with a little coin.

Thanks for this.