Notable Sandwiches #78: Gyros

On spit-roasted mediterranean meats....and Jane Eyre

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where we trip merrily through the bizarre and mutable document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week: gyros.

Dear readers, it is with a heavy heart that I write this column about gyros.

Not that I have an especial reason for having a heavy heart, certainly not one connected to this week’s sandwich, unless it be the insalubrious influence of Charlotte Brontë (I am presently reading “Jane Eyre” and find myself taken to the grounds of Thornfield House most thoroughly, with all the woe and transports of love therein). Many writers have their own private parlance for the moods that accompany the vagaries of their trade; as for me, I say “the good hand is on me” when the words flow easily, and term it “the black hand” when they lie straitened and sluggish through the narrow corridor between mind and hand, and it is the black hand that reigns presently, ungovernable and suffocating. I blame this externality for having little to say on the subject of this great and famous sandwich, of which thousands are purveyed each day in America alone, principally in the many diners, stands and shops that are the demesnes of the Greeks of New York and Chicago and elsewhere.

The gyro itself is quite similar to the doner kebab, which we have already discussed at some length (see below), but carries some originalities: first of all, and in distinction from the Muslim countries which joined Greece under the yoke of the Ottoman empire for centuries, the Greek gyros (the word meaning “to turn or revolve,” referring to the ubiquitous cone of meat turning and turning in its tapering gyre) is principally of pork. In many instances it is also forcemeat made with bread crumbs, leading to the loafish melting in the mouth; and the yogurt sauce that accompanies it is Greek tzatziki, rather than Turkish cacik, which is a game of syllabic transposition that suborns the Turks and raises high the Hellenic gonfalon.

Empire plays its role in this sandwich, as it does in the history of many sandwiches: specifically, the proliferation of gyros in the West owes to an outflux of Greeks from the former grounds of the Empire at the ending of World War I, which saw, too, the collapse of that once-great imperial bastion. Out of the empire flooded Greeks and Armenians, the latter the subject of unimaginable slaughter, after its collapse in 1922; emigres turned by necessity into geniuses of purveyance began creating gyro stands and shops wherever they landed, and turned the street food into a toothsome ubiquity.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

The Greeks, in the many sources compiled by my invaluable editor on this subject, attribute the creation of this sandwich to no less august a person than Alexander the Great, whose great armies needed victuals to feed their great march out of Macedon, and may thus have turned to the application of slivers of meat to flame and thence to their stomachs. This smacks, however, of myth, and a myth specifically designed to differentiate the gyro from its close cousins, doner and shawarma; myth is often resorted to in the culinary realm, being such an aid to the selling; credulously subscribed to, it is cloying and false; nonetheless in this case I find myself reveling in the imagining of that great man—indeed given the appellation The Great—consuming gyros in the misty eons of the past, and thus rendering a food made greatly popular by conquest into the food of a conqueror. It is a neat transposition, and in any case the emperor having died in his youthful years and still more millennia ago is not available to quiz on its truth: so let them have their myth; it was Alexander’s army that first made the gyros turn, and our mouths that, in loving it, unwittingly speak his legacy.

When I write under the black hand my own hands hardly move; I am numb and fixed; my ideas are tame when they should be wild; words that when their best selves dance for me like sylphs and sprites are still as frozen seas, and chill me as fully; thus I end this missive more quickly than it ought to end, and more abruptly; like a good gyro time and heat are needed to assuage my ills. Reader, I beg you forgive me for this lapse. I return to the Brontës now—planning hereafter to read “Villette” and “Wuthering Heights” and indeed all the rest of their oeuvre—with an unsettled heart, having ill fulfilled my duty; still, I think of the great Emperor perched before a fire, with his little pieces of savor, shreds of meat turned and turned again, to fuel his conquest, and I smile a little, at the juxtaposition of the humble and the Great; and I hope you find in your own time such a congruity of the great and the small as to give you a frisson of joy at this lively dissonance; and I leave you,

Your own,

Talia

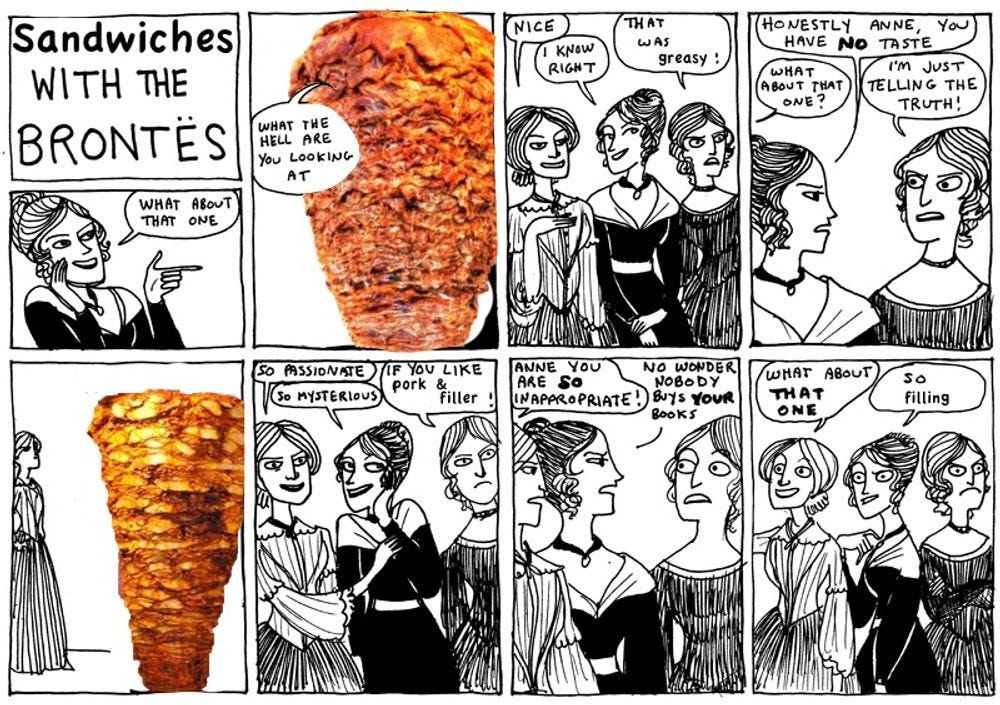

An addendum, courtesy of Kate Beaton’s comic strip by way of reader Tweety Fish:

Being of a certain number of years, sometimes I'm reminded of the fact that certain food that's easy to find now, it simply didn't exist in the generic white bread world when I was a kid. Gyros sandwiches are one of these things.

Other examples: Croissants. Yogurt. Even bagels. 1970, if we were aware of them at all, they were the stuff of foreign countries or urban ethnic neighborhoods. By 1980, they're staples.

I regret the pain of the black hand, yet this still dances. Wuthering Heights, though--now there's a dangerous trip. Be sure to crank up Kate Bush somewhere during your read.