Notable Sandwiches #9: A Tale of Two Sandwiches

Melted cheese and historical memory in Chile

Welcome to the latest installment of Notable Sandwiches, the series in which I faithfully chronicle the bizarre and twisted document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order.

Time hollows us all out in the end, grinds our legacies into dust. Percy Bysshe Shelley did a rather famous riff on this timeless axiom, with his poem “Ozymandias”: vast and trunkless legs of stone, the whispering desert winds carrying off the once-omnipotent emperor’s mouthy little epitaph—look upon my works, ye mighty, and despair. But Ozymandias the historical figure is rather a curious choice to use to make this point. Ozymandias is his Greek name; he was known to his Egyptian subjects as Rameses II, or more commonly, Rameses the Great; he was known as the “Great Ancestor” by his successor kings, and considered to be the most exalted and mightiest of all Ancient Egypt’s pharaohs. Three thousand, two hundred and thirty-three years ago, he was entombed, not under a broken statue, but in the Valley of Kings. His life and extensive military campaigns have been exhaustively documented, surviving in Greek, Hittite, Nubian, Punic and Egyptian sources from the time. His consort Nefertari remains a worldwide symbol for alluring and sensual beauty; he built her tomb, which survives, along with the enormous and imposing temple at Abu Simbel.

He was also portrayed, indelibly, by Yul Brynner in The Ten Commandments—a cinematic legacy of sexy, muscular glowering. I mean, death is inevitable, and time erodes what faint memory of us may follow that great and unknown abyss, but Rameses II is a spectacularly bad example of that particular truth. There are all kinds of legacies—in stone, in story—and he has all of them, this man who was a ruler so great they called him “The Great.” Only in one respect is the legacy of Rameses lacking. The sole lacuna—the one place where the desert winds can still whistle mockingly at him—is that he has no namesake sandwich, not anywhere.

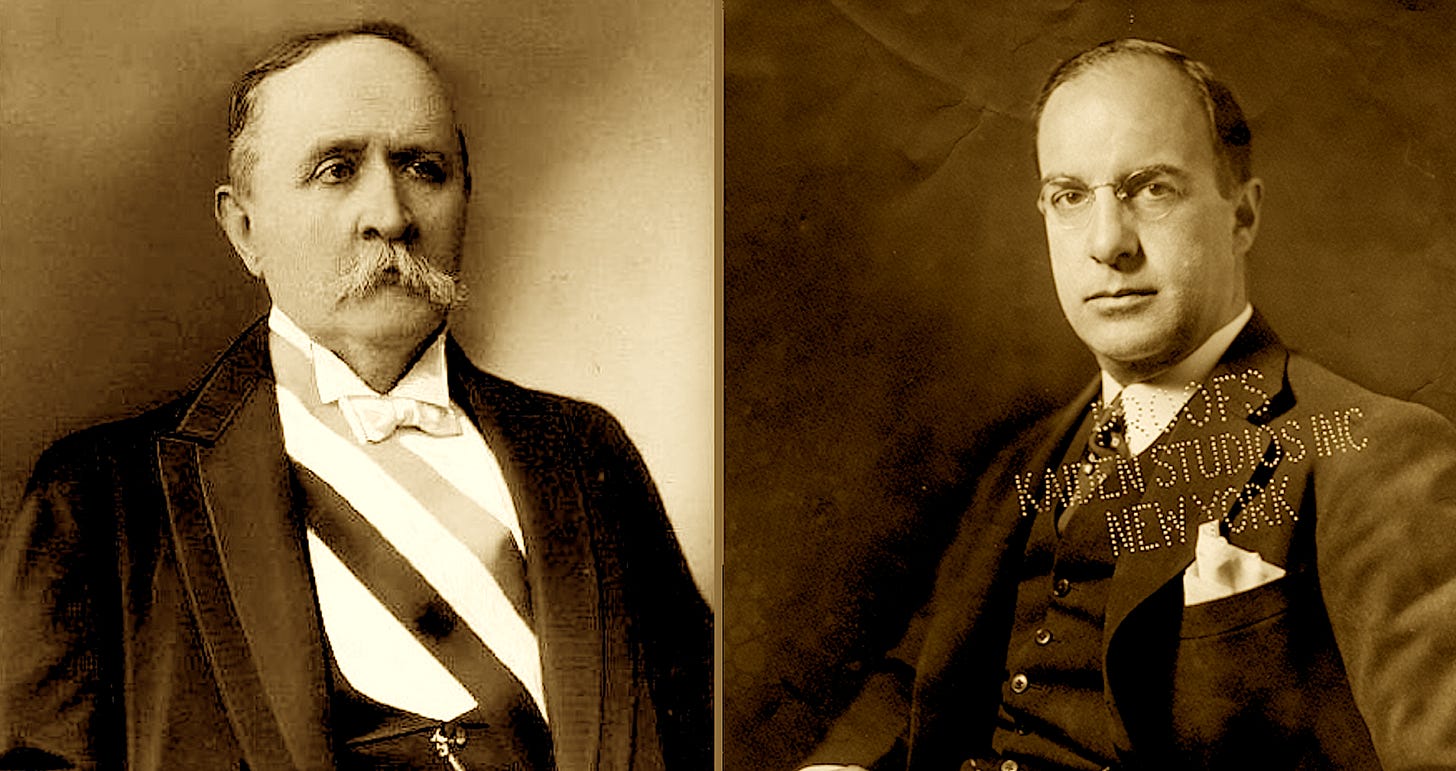

The same cannot be said of a pair of Chilean politicians, Ernesto Barros Jarpa and Ramón Barros Luco, who gave rise to two of the most iconic sandwiches in all of Chilean cuisine: the Barros Jarpa and Barros Luco, which are our next two entries in Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. These were not, in their time, obscure or ancillary figures: Barros Luco (1835-1919) was the President of Chile from 1910 to 1915. Barros Jarpa (1894-1977), a cousin, occupied numerous exalted stations in the Chilean government: he served as Foreign Minister no less than three times (1922, 1926, 1942), as Minister of the Interior (1932), as a member of the Chilean Supreme Court, as a professor for four decades at the University of Chile, and editor of two newspapers, La Nación and El Mercurio. Barros Jarpa’s distinguished executive-branch career ended in 1942, when his long-advocated policy of official neutrality in World War II was superseded by Chile’s declaration of war on the Axis.

Both were also big fans of sandwiches, and ordered them so often—either at the café of the National Congress of Chile, an imposing classical-looking building in downtown Santiago famed for its gardens, or at the nearby culinary institution Confiteria Torres, which dubs itself the oldest restaurant in Chile and is still slinging sandwiches and pisco sours to stalwarts—that they each gained a namesake sandwich. In Chile, that is no small thing.

“Sandwiches are very important in Chile. Even if you are a chef, you can specialize in sandwiches. That’s a complete profession, and it’s called maestro sanguchero, master of the sandwich,” Pilar Hernandez, a Chilean food blogger and coauthor of the cookbook The Chilean Kitchen, told me. “In many places, coffee places and small restaurants, they will have the griddle going all the time to make all the sandwiches.”

The barros luco—a thin-sliced steak-and-cheese on the country rolls known as pan amasado or the baguette-like marraqueta—is roughly equivalent to the American cheesesteak, and ubiquitous throughout Chile. “The barros luco is cheese and meat, it needs to be beef. A thin beefsteak. Here in the US you can use top sirloin,” says Hernandez. “But usually it’s cut thin, not pounded—subtle differences, but we are so invested in our sandwiches that I feel I need to tell you.”

Apparently, Barros Luco el Presidente—a robust and scowling man, even in his youth impressively mustachioed—preferred steak; his cousin Barros Jarpa opted, instead, for ham. The barros jarpa sandwich, accordingly, is a simple ham-and-melted-cheese affair on soft-crumbed pan de miga. They are everyday sandwiches, says Hernandez, of the type children would bring to school. They’re available for breakfast and lunch at cafes that specialize in the art of the hot griddled sandwich; a quick Google Images search of “Chilean restaurant menu” underscores the point—any place that serves sandwiches serves either a barros jarpa, a barros luco, or both. And the sandwiches have completely and utterly eclipsed the lives of these men, so powerful in their lifetimes. Barros Luco, in particular, had a relatively undistinguished history for a president, known in his executive capacity for profound and deliberate apathy. He presided over the explosive growth of Chile’s exportation of nitrate fertilizers, which quickly overtook the bat-guano standard as the primary fertilizer throughout the world. His emphatically hands-off approach to actual governance meant that little of the burgeoning wealth reached the hungry masses, and extraction quickly devolved into exploitation by would-be nitrate barons, according to Hungry for Revolution: The Politics of Food and the Making of Modern Chile, by Joshua Frens-String.

“They’re only remembered because of the sandwiches,” Hernandez affirms. “To be honest, they’re not the most important presidents or ministers or anyone like that. The sandwiches are more famous than the guys.”

The overall effect, transposed into American terms, would be if William Howard Taft, whose term overlapped with Barros Luco’s and who is currently best known among the non-history-nerd masses for getting stuck in a White House bathtub, had an a common food item named after him. Like if the tuna melt was the Taft Melt. Or perhaps, given Taft’s famous heft, if the club sandwich was the Taft Stack? (There are, of course, myriad sandwiches named after individuals across the U.S., but none have achieved the ubiquity of the Barros legacy in Chile.)

There’s a certain irony to it all—famous and important men like to be known for famous and important and probably martial and masculine achievements, not the humble kitchen gentleness of a sandwich. Only if you’re Rameses II can you choose your legacy, Abu Simbel in all its glory. For everyone else, abyssal obscurity beckons—and you could do worse, in cheating it, than lending your name to a sandwich that thousands eat every single day, that mothers make for their children, that workers use to nourish themselves for the day’s labor. Look upon my works, ye mighty—they’re delicious. 🥪

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Barros Luco Sandwich

By Pilar Hernandez

I don’t remember my first Barros Luco sandwich, but I do remember I became an expert during college. My college cafeteria had a great “Maestro Sanguchero,” and my favorite quick lunch was a sandwich.

Prep Time: 10 minutes

Cook Time: 10 minutos

Total Time: 20 minutes

Yield: 4 1x

Ingredients

4 brioche rolls or crusty french rolls

4 thin top sirloin steaks (ask to be cut for Milanesa if your supermarket is Latino), room temperature

8 thick slices of Havarti cheese

salt and pepper

a wide non-stick skillet or a flat griddle

Instructions

Heat the griddle or skillet over medium heat.

Pat the steaks dry with a paper towel and salt and pepper on both sides.

Cut the rolls in half. Heat them in the corner of the griddle.

Brush the griddle with butter and place the steaks. Cook 1-2 minutes per side until seared and brown.

Lay the cheese on top of the steak and allow it to melt.

Assemble the sandwich: bread (with the juices)-meat-cheese-bread.

Serve immediately.

look upon my sandwiches, ye vegetarians, and despair...