Notable Sandwiches Summer Special: The Prison Sandwich

A guest post on one lunch you'll want to avoid, by someone who knows

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature in which I, alongside my editor David Swanson, trip merrily through the profoundly odd and ever-changing document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week we’re turning things over to Keri Blakinger for a special edition on a sandwich we’d encourage all readers to do their best to avoid ever sampling: the prison sandwich (which is blessedly absent from the Wikipedia list.) Thankfully for us, Keri is one of America’s foremost chroniclers of the criminal justice system, so you can learn about this accursed foodstuff without consuming it yourself. Keri herself wasn’t so fortunate. She tells her story of life behind bars in “Corrections in Ink: A Memoir,” a harrowing new memoir published last month by MacMillan. —Talia

Ever since the birth of this foodie-friendly substack, I have been lusting after this space, patiently waiting for the part of the alphabet that covers my particular area of sandwich expertise: prison sandwiches.

But the alphabet is long and my patience has run out, so Talia has graciously allowed me to step in with an out-of-the-ordinary entry on what passes for a sandwich behind bars. That may seem like an unusual area of expertise, but my interest here is personal: After years of struggling with heroin addiction as I bumbled my way through college, in 2010 I was arrested with a small Tupperware container full of heroin and wound up in a county jail in upstate New York.

There, for several weeks, I lived almost exclusively on sandwiches—because I was vegetarian and the meatless menu consisted mostly of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for lunch and cheese sandwiches for dinner. Occasionally, they’d switch things up and serve the cheese first. But a few weeks in, a new sheriff took over and the jail cut meatless and lactose-free meals—so for the rest of my stay, I lived mostly on popcorn, Jolly Ranchers, and weird concoctions of commissary items (see below.)

Eventually, I was transferred to a prison upstate, where the food was a little better, the commissary choices a bit more varied, and the meatless options a lot easier to come by. In general, the food was not great, but not awful. That is, the portions were adequate and the ingredients identifiable—though sometimes they included cockroaches or hair. But out of all the things we complained about in prison, food was not high on the list. At the time, I didn’t know how lucky that made us.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

When I got out in 2012, I went on to become a journalist, first at the Ithaca Times, then the New York Daily News, and eventually at the Houston Chronicle. In 2017, after the Chronicle's death penalty reporter retired, I found myself back on familiar ground, on the prison beat. Some of the first tips I got were about the abysmal food served in the Lone Star State’s lockups—especially the always-meager and sometimes-moldy sandwiches that came in the bagged meals served whenever one of the prisons went on lockdown. But despite the frequency and volume of the tips, I quickly realized that food-focused allegations were incredibly hard to prove. By the time I left the Chronicle for The Marshall Project in early 2020, I hadn't managed to nail down any hard evidence of how bad the lockdown fare really was. What I really needed were samples—or at least some pictures.

Then came the pandemic.

During the first year of Covid, Texas’s roughly 100 prisons stayed on lockdown for unprecedented durations. That meant prisoners didn’t get out of their cells for recreation or jobs or vocational programs—but it also meant they didn’t get out to go to the mess hall. Instead, the guards delivered meals to their cells, tossing in questionable grub at irregular times—maybe breakfast at 3 a.m., or dinner at midnight.

As the lockdowns dragged on, prisoners across the country spent longer and longer confined to their cells and bunks—and more and more of them began taking a new risk, using contraband cell phones to post details of their incarceration on the internet, and to reach out to reporters.

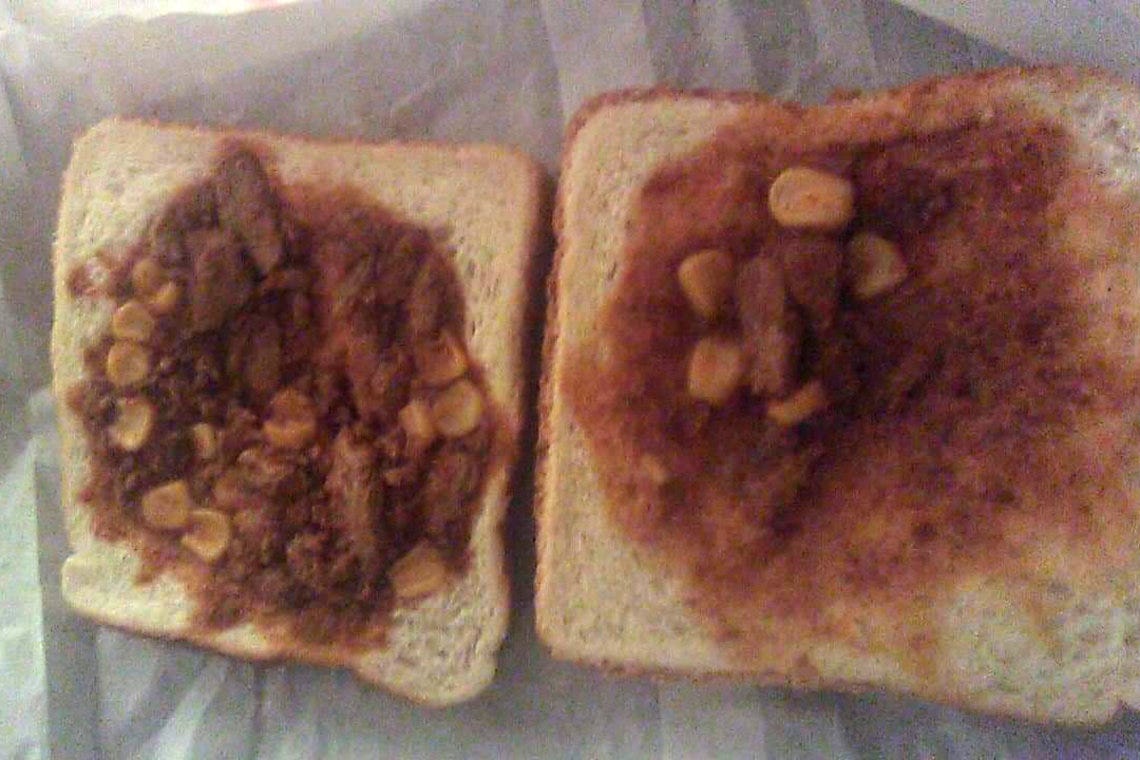

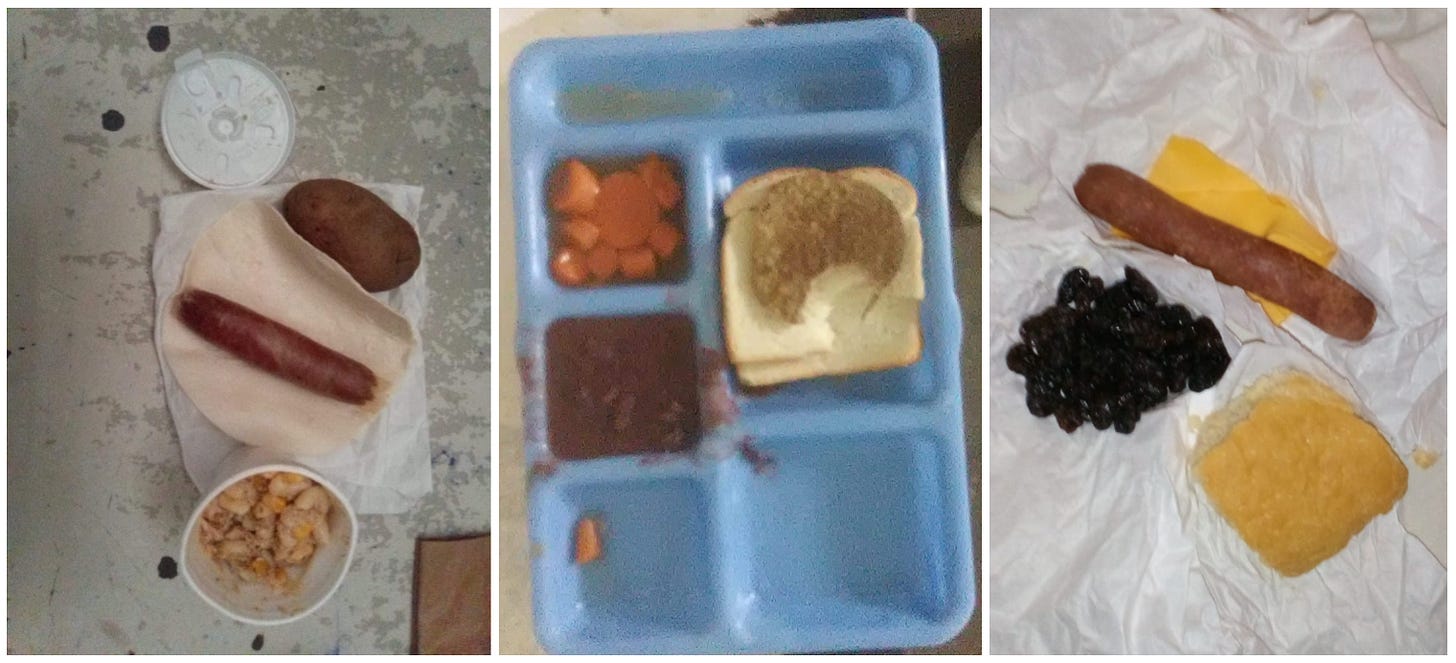

When some men in Texas started sending images of the food they’d been served, I was appalled—but I also realized this was my chance to show the world. Finally, I had proof. In the image prisoners sent, there were sloppy joes that looked like peanut butter sandwiches studded with corn kernels, graying hot dogs wrapped in white bread, and powdered milk—served dry—with each meal. There were no vegetables, and the only consistent fruit offerings were daily handfuls of raisins and prunes. One particularly memorable meal included a hot dog with no bun, a single tortilla shell, a cup of unidentifiable mush and a whole, uncooked potato (see photo, below.)

This was nothing like what I’d encountered when I did time, and far worse than the images I’ve seen from other prison systems. But in some ways it was utterly predictable: Even before the pandemic, the sprawling Texas system never had enough staff or money to adequately care for the then-145,000 inmates in its custody. And when it came to food, the state had purposely cut corners, eliminating hot dogs buns and liquid milk during an especially tight budget year in 2011, and giving some units only two meals a day on the weekends.

In mid-2020—after I wrote about it for the first time—the food improved slightly. Officials in the Huntsville central office ordered staff to stop handing out moldy bread and start serving produce. A few excited prisoners with sent me pictures of verdant vegetables and miraculously unspoiled fruit. Officials vowed to provide thousands of tray lids so that they could offer warm meals during lockdowns. Advocates pushed for more funding for prison food. Frankly, I was pretty pumped. As a journalist, you hope for stories that have an impact on people. And as a journalist who did time, that impact just hits a little different when those people are in prison.

But of course, Texas is Texas, and the legislature did not allot more money for food. (Instead the governor took money out of the prison budget to fund his border security initiative which has, so far, had questionable results.) By early 2021, the meals had already begun creeping back toward vegetable-less slop when the deep freeze hit and the Lone Star State’s power grid failed, plunging millions of Texans into darkness. Once again, prisoners began getting paper bags of unidentifiable sandwiches at unpredictable hours—while also grappling with overflowing toilets, cold cells and a lack of blankets.

This time, my reporting on the shoddy meals didn’t lead to any promises of change—though after the lights went back on and the lockdowns ended, people at least started getting regular mess hall trays again. Based on the latest pictures they’ve sent, those offerings aren’t much better. There are a few vegetables here and there, but a lot of the time it still doesn’t look like enough food to feed a grown human.

Which brings me to this week’s sandwich recipe: The Jailhouse Burrito. I know, I know, technically, this is not a sandwich. It was something we made from time to time in the county jail—but in prison systems where the food is far less edible, this sandwich-adjacent staple does a lot more to keep people full than the shit that comes out of the mess hall.

“Jailhouse Burrito” Recipe

Ingredients

Single-serving bag of nachos

Packet of ramen noodles

Optional Ingredients

Whatever cheese-like items are available on the commissary where you’re locked up

Summer sausage or other meat item

Pickles

Refried beans

Instructions

Open the bag of chips and crush them up.

Throw the package of Ramen noodles to crush them up, too. (It’s not really necessary to crush them up on the floor but that’s just how it’s done in jail. Sorry, I don’t make the rules.)

Dump the Ramen into the bag of chips, and crush some more until everything is broken into little pieces, like your soul. Then add only half a pack of Ramen seasoning—because this whole mess is already salty as hell and you will regret it if you add the whole thing.

Add any extras you have from the commissary, like squeeze cheese or dehydrated refried beans. If you’re adding items that require slicing and dicing —like summer sausage or pickles—you’ll need to use your prison ID card as a cutting implements since you probably don’t have access to a knife.

Pour hot water into the bag, just enough to cover everything. How do you get hot water in prison, you ask? It varies. If you’re lucky, you might have access to a microwave, but more likely you have access to a hot pot or aren’t afraid to get creative with a live wire in order to make the jailhouse heating device known as a “stinger.”

Roll the bag up so the contents are in a log shape at the bottom. Let the entire mess sit for 3 to 5 minutes or until congealed.

Cut away the chip bag (probably with your teeth) and transfer the congealed burrito-shaped log of chips and noodles onto a plate. Note: If you’re someplace with a nice commissary selection, you might actually have a tortilla to wrap this in—but usually you just eat this semi-solid mess with a plastic fork and tell yourself it’s a burrito.

Top with whatever relevant sauces are available—possibly salsa, but probably just ketchup and packets of mayo jacked from the mess hall.

Admittedly, the outcome looks like brains. So maybe close your eyes when you take that first salty bite—and remember the piss-poor culinary offerings that prompt people in prison to start experimenting with such dicey-looking combinations of noodles and snacks in the first place.

Now, I know that there are people who say prisoners don’t deserve edible food. “Don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time.” But that response—which is, frankly, tired A.F.—is never really about the time. Everyone in prison can do the time. It’s the abuse and degradation that really take a toll. And here’s the thing: the vast majority of prisoners will get out some day, and treating them like animals in the meantime will not aid in rehabilitating them. It will not increase their chances of staying out of prison. It will not improve public safety. And, if nothing else, it seems like prisons should at least do that.

If it won’t improve public safety, serving half-portions of unidentifiable food will do one thing: It’ll ensure a steady supply of alternative jailhouse recipes to entertain the internet. Imitation Laffy Taffy made with powdered creamer. Cheesecakes flavored with Kool-aid. Jailhouse burritos. Penitentiary tacos. At least somebody’s getting something out of prison, I guess.

As a foodie, this sort of writeup is enough to keep me on the straight and narrow and never, ever risk going to jail!

Seriously tho', this is just appalling -- how can we treat other human beings like this, especially if we ever claim to want to rehabilitate people who end up in the prison system? What happened to basic human decency?

WOW- excellent-and disturbing. A stunner.