On Antifascism

What is it? What does it look like? And how does it manifest in the real world?

What is antifascism? The simplest explanation is also the truest: antifascism exists in relation to fascism as antimatter does to matter—its opposite, and, hopefully, its equal. As fascism rises and spreads, so does the need for antifascism, and the people attracted to its cause. “Fascism,” as broadly understood amongst the international, highly diffuse and individuated network that constitutes the antifascist movement, is defined quite narrowly, as the words and actions of those who espouse a politic of genocide, who seek to destroy and harm members of marginalized groups, who openly or covertly align themselves with past and present fascistic movements, and who agitate for or commit acts of violence against the minorities they despise.

So much, so simple. The second component, however—and perhaps what makes the concept of antifa so baffling and inimical to a media sphere that aligns itself most readily with institutions and with the state—is that antifascists are nonstate actors, individuals and collectives acting from no authority but their own desire for a better world. Antifascism has a century’s history behind it: there were the arditi del popolo—“The People's Daring Ones”—who fought against Mussolini’s Partito Nazionale Fascista in Italy. In the 1930s, socialists and trade unionists stood against Hitler’s rising Brownshirts under the banner of Antifaschistische Aktion. In 1936, thousands of volunteer fighters from all over the world who joined together in the fight against the would-be military dictator Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. It’s from the latter conflict that an antifascist slogan, used all around the world, arose, Dolores Ibarrurri’s war cry:

They shall not pass! This is the antifascist position: arrayed in defense against an encroaching force of destruction and violence, sacrificing their effort and their bodies to protect all they hold dear.

After World War II, independent antifascist movements arose. One was the 43 Group—Jewish soldiers who had fought for Britain and returned, only to find a rapidly-growing movement of former Nazis and British fascists declaring that the “gas chambers weren’t enough.” Finding the authorities lax and permissive, the 43 Group took it upon themselves to thwart fascist rallies with their fists, and drive Hitler’s acolytes from the public sphere.

During the latter half of the twentieth century, antifascist movements arose wherever neofascist and far-right movements took root. In Germany, a group called the Autonomen pioneered the “Black Bloc” approach, covering their faces and wearing anonymizing black clothing to evade detection by police and revenge from the fascist groups they sabotaged. By 1989, antifa groups—the German short form of antifaschistische aktion—were organized in ten German cities. Punk squatters, feminists, queer people and immigrants banded together to fight back against a wave of anti-immigrant violence that swept the country in 1990 as the police passively stood by.

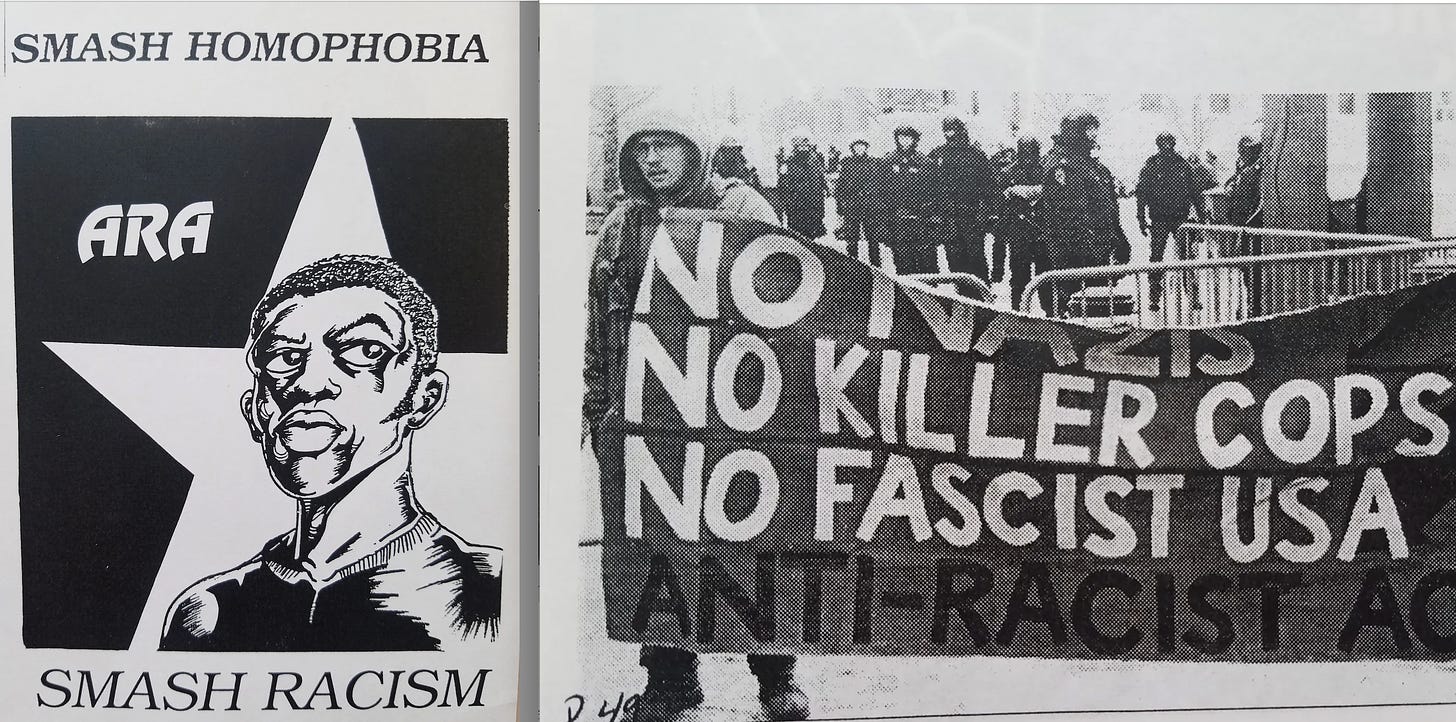

In the United States, antifascists congregated in the punk-rock subculture, where racist skinheads, drawn to the white-supremacist anthems of neo-Nazi bands, threw sieg heils and sought to drive people of color out of the scene with violence. In the 1980s, two decentralized organizations, S.H.A.R.P (Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice) and the A.R.A. (Anti-Racist Action) drew from anti-fascist forebears to do battle with Nazi punks, the Klan, and fascist-sympathetic police. As the Dead Kennedys famously put it in 1981, their goal was simple—to make Nazi punks fuck off.

The first U.S. group to take on the moniker “antifa” was Rose City Antifa, in Portland, whose radical leftist roots—and their militantly racist opposition—run deep. In October of 2007, an “Ad Hoc Coalition Against Racism and Fascism” gathered to shut down a neo-Nazi punk festival called Hammerfest in the city, and has continued to work to dismantle organized bigotry in the Pacific Northwest ever since.

This fierce, tender and urgent history is a direct counterpoint to the menacing image of antifa popularized by conservative and centrist media. The antifascist world is full of brave, complex, often female and queer-led collectives through which people reach out to one another, grasp hands, and turn to face the threat, stronger in one another’s company. It’s hard, however, to put a face on antifascism, friendly or otherwise. For protection against the brutality of the fascists they oppose, and in order to avoid concentrating power in any given individual, antifa is largely anonymous, and decentralized.

Like everything else about antifascism, this is a defensive position, part of the three-way fight that antifascists are constantly engaged in, as nonstate actors at odds with both organized hate groups and a brutal, racist law-enforcement apparatus. Fear-mongering about antifa has spread widely—think of the menacing news clips about the dangers of antifa, the mewling objections of centrist pundits, calls by Donald Trump and the Heritage Foundation to crush antifascism with federal force. But far from being an all-powerful bogeyman, as the right views it, or an embarrassment to civility, as too many on the left and center view antifa, it is a movement of reaction, which operates as a bulwark against extant and encroaching fascism. It’s a movement of protection, and is not a thoroughgoing political philosophy, but rather a set of tactics and a commitment to that protective stance.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

One of the things I love about antifascism—and the reason I feel comfortable defining myself as an antifascist, though it’s not a sole political valence in and of itself—is the multiplicity of means and uses that go into the term. There are many methodologies and roles for antifascists; although this is elided by ungenerous and alarmist press coverage, street violence—countering fascist marches by physically interposing oneself between fascists and the public—is just a small nexus of antifascist activity, one of a broad spectrum of activities that constitute antifascist struggle. Methods to thwart fascism are at least as variegated as the ways to spread it, if not more so.

Antifascism can utilize the full spectrum of human creativity: there are those who create antifascist art to undermine the spread of genocidal propaganda, and music that invigorates and inspires. There are those who provide food, clothing, safety gear, childcare and water to street operatives; those who work bravely as street medics, bandaging wounds and flushing tear gas from weeping eyes; and there is a whole range of activities, in the Internet age, that occur from behind the keyboard. These include infiltration and surveillance of fascist groups, and relaying gleaned intelligence to others in order to anticipate fascists’ movements. There is the calculated sowing of internal discord to thwart fascist operations—and intentional sabotage of logistics. There is the digital detective work of unmasking the identities of those who seek to harm and threaten minorities from beneath the veil of anonymity, pairing ugly words and threats to real names and faces. There is the work of writing and education, whether journalistic or in the form of community resources to keep people aware of the state of fascist movements in their country or city. There are those who call for boycotts of places that host fascist conferences, to provide disincentives to corporations to take fascists’ money. There are those who target the advertising and monetization of fascist blogs, shops and video channels, or seek to deplatform fascist ideologues from social-media perches that enable them to recruit.

I am proud to be an antifascist, proud to be a part of a movement that works without external aid, against those who seek to create a racially cleansed, forcibly straight, Jewless world. Street fighting is necessary when fascists march, but so are espionage, education, music, art, support; none of these activities are less or more antifascist. Each are necessary, each are complementary, each are part of the broad, sprawling, individuated effort of building a dike against the rising tide of violent cruelty that threatens to sweep away our world.

I stand with you! The fascists only win if they aren’t opposed every time they try to act.

Beautifully written