Welcome back to Culture Club, a feature where David and I write about what we’ve been reading, watching, playing, and listening to, for paid subscribers. Please enjoy this free preview, and consider upgrading to support two struggling journalists at once! — Talia

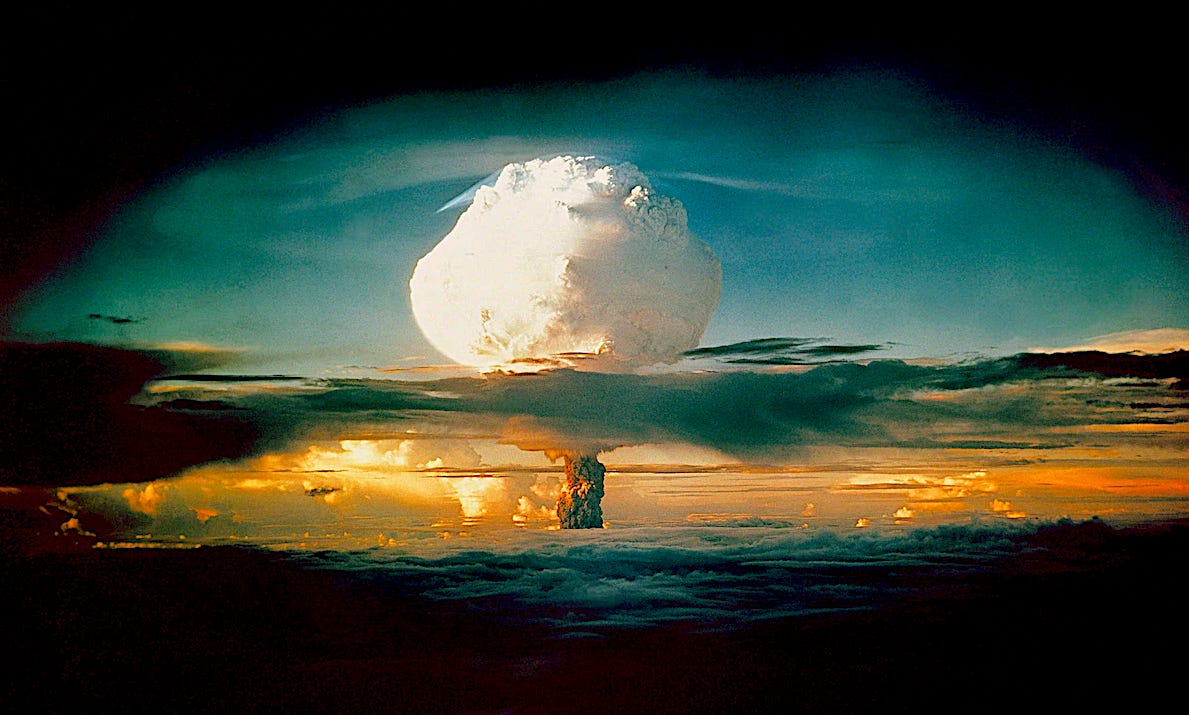

At exactly thirty minutes past five in the morning, on July 16, 1945, Mountain War Time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above the Jornada del Muerto desert basin in New Mexico, J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life changed forever. So, too, did the course of human history, though the only people who knew that at the time were Oppenheimer and his Manhattan Project colleagues, who watched the Trinity Bomb Test together.

“A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent,” Oppenheimer later recalled. “I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty, and to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘now I am become Death , the destroyer of worlds.’ I supposed we all thought that, one way or another.”

In Christopher Nolan’s new biopic, which opened in theaters on Friday, Cillian Murphy’s Oppenheimer reads the quote in the middle of a tryst with Jean Tatlock, played by Florence Pugh. This scene, however cinematic, seems unlikely to have occurred, and early accounts of Oppenheimer’s life differ in both the origin and the translation of the quotation.

According to a Time magazine cover story in 1948, he learned it from Arthur Ryder, a professor at Berkeley: “Ryder taught Oppenheimer to read the Hindu scriptures in Sanskrit, his eighth language. Oppie still reads them, for his “private delight” and sometimes for the public edification of friends (the Bhagavad-Gita, its worn pink cover patched with Scotch tape, occupies a place of honor in his Princeton study).”

A LIFE magazine cover story the next year added some details: “And then when the great ball of fire rolled upward to the blinded stars, fragments of the Bhagavad-Gita flashed into his mind: ‘If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the Mighty One... I am become death, the shatterer of worlds’.”

And, the New York Times’s 1954 obituary of Oppenheimer seemingly had the last word: “As he clung to one of the uprights in the desert control room that July morning and saw the mushroom clouds rising in the explosion, a passage from the Bhagavad-Gita, the Hindu sacred epic, flashed through his mind. He related it later as: ‘If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the Mighty One.’ And as the black, then gray, atomic cloud pushed higher above Point Zero, another line — ‘I am become Death, the shatterer of worlds.’”

Those are just a few of the articles I dug up this weekend, having gone deep down the atomic rabbit hole in anticipation of Nolan’s new movie. Like many other history buffs and cinephiles, I am making my way through American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the 2005 Pulitzer Prize-winning biography by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherman. It’s a heavy lift, though, and if you don’t have the patience for a 700-page saga, this selection of articles and essays should provide a good start. I’ve included contemporary coverage of the bombing of Hiroshima, early profiles of Oppenheimer the hero, accounts of his fall, and John Hersey’s legendary reporting on the destructive legacy of the nuclear bomb.

78-years after that first detonation in the New Mexico desert, it’s clear that Oppenheimer indeed left the world shattered. Whether it ends up destroyed is still to be seen.

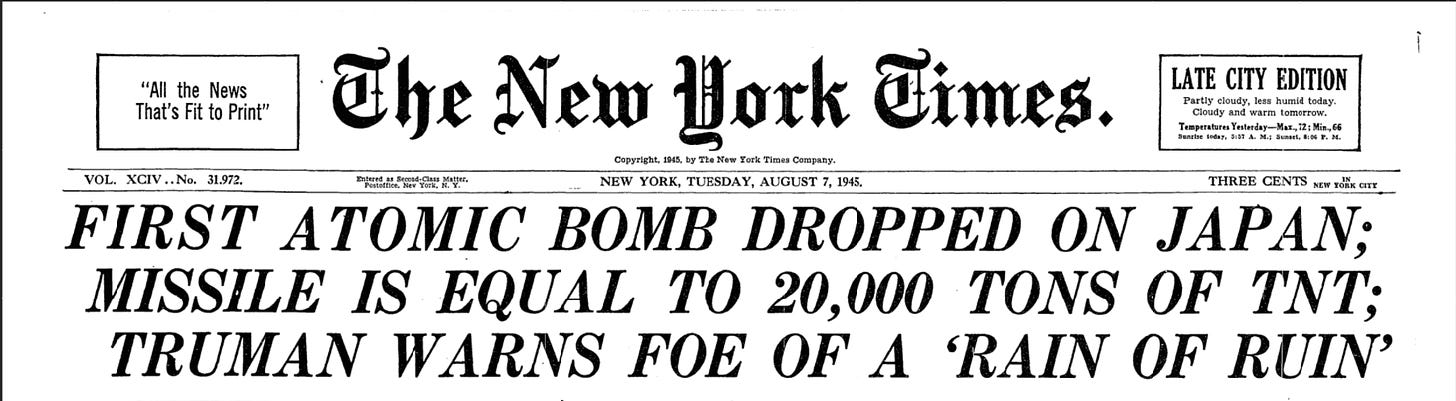

FIRST ATOMIC BOMB DROPPED ON JAPAN

The New York Times, August 7, 1945

What happened at Hiroshima is not yet known. The War Department said it “as yet was unable to make an accurate report” because “an impenetrable cloud of dust and smoke” masked the target area from reconnaissance planes. The Secretary of War will release the story “as soon as accurate details of the results of the bombing be come available.”

But in a statement vividly describing the results of the first test of the atomic bomb in New Mexico, the War Department told how an immense steel tower had been “vaporized” by the tremendous explosion, how a 40,000-foot cloud rushed into the sky, and two observers were knocked down at a point 10,000 yards away. And President Truman solemnly warned:

“It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Postdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air the like of which has never been seen on this earth.”

CLUE TO EXPLOSIVE IN NEW BOMB TOLD

By William S. Barton

The Los Angeles Times, August 13, 1945

Who is the inventor of the atomic bomb?

As in every great discovery the story is never told by singling out one man — scientific knowledge is cumulative and each discoverer stands on the shoulders of the hundreds who preceded him. But it is a dramatic circumstance that in this instance one man has been acclaimed above all others in the announcements.

“The development of the bomb itself,” asserted Dr. Ernest O. Lawrence, famed University or California atom smasher, “has been largely due to Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer's genius and the inspiration and leadership he has given to his associates.” Similar statements may have to be amplified when the whole story is told, but it now appears that when, in the future, anyone with a penchant for simplification lists the name of the bomb inventor it is apt to be Oppenheimer. Who is he?

The Atom Bomb As a Great Force for Peace

By J. Robert Oppenheimer

The New York Times, June 9, 1946

There is only one future of atomic explosives that I can regard with any enthusiasm: That they should never be used in war. Since in any major total war, such as we have lived through, they will most certainly be used, there is nothing modest in this hope for the future: It is that there be no such wars again…

My own view is that the development of atomic weapons, if wisely handled, can make the problem more hopeful rather than more hopeless. This is so, not merely because it intensifies the urgency of our hopes — in frank words, because we are scared. It is so because it provides new and healthy avenues of approach. In developing these avenues the fact that there is a far-reaching inseparability of the constructive and destructive applications of atomic energy, the fact that at first sight would seem to make the problem more hopeless, is precisely the central vital fact which makes the solution possible at all. If we remember this, we may have a guide for the future.

Hiroshima

By John Hersey

The New Yorker, August 23, 1946

At exactly fifteen minutes past eight in the morning, on August 6, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and was turning her head to speak to the girl at the next desk. At that same moment, Dr. Masakazu Fujii was settling down cross-legged to read the Osaka Asahi on the porch of his private hospital, overhanging one of the seven deltaic rivers which divide Hiroshima; Mrs. Hatsuyo Nakamura, a tailor’s widow, stood by the window of her kitchen, watching a neighbor tearing down his house because it lay in the path of an air-raid-defense fire lane; Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge, a German priest of the Society of Jesus, reclined in his underwear on a cot on the top floor of his order’s three-story mission house, reading a Jesuit magazine, Stimmen der Zeit; Dr. Terufumi Sasaki, a young member of the surgical staff of the city’s large, modern Red Cross Hospital, walked along one of the hospital corridors with a blood specimen for a Wassermann test in his hand; and the Reverend Mr. Kiyoshi Tanimoto, pastor of the Hiroshima Methodist Church, paused at the door of a rich man’s house in Koi, the city’s western suburb, and prepared to unload a handcart full of things he had evacuated from town in fear of the massive B-29 raid which everyone expected Hiroshima to suffer. A hundred thousand people were killed by the atomic bomb, and these six were among the survivors.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sword and the Sandwich to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.