Prophets of America

As the influence of mainstream Christianity shrinks, the prophetic movement is growing

Edited by David Swanson

In 1839, in Trout Creek, New York, in the sparsely-populated hinterlands of Delaware County, a prophet was born.

His name was Cyrus Teed, and in 1869 he claimed to have transfigured lead into gold in his laboratory. That very night he was struck with a prophetic vision: God appeared to him as a beautiful woman, who separated Teed from his body and blessed him while he stood in a numinous spirit-state. “I have brought thee to this birth to sacrifice thee upon the altar of all human hopes,” God told him, “Thou art chosen to redeem the race.”

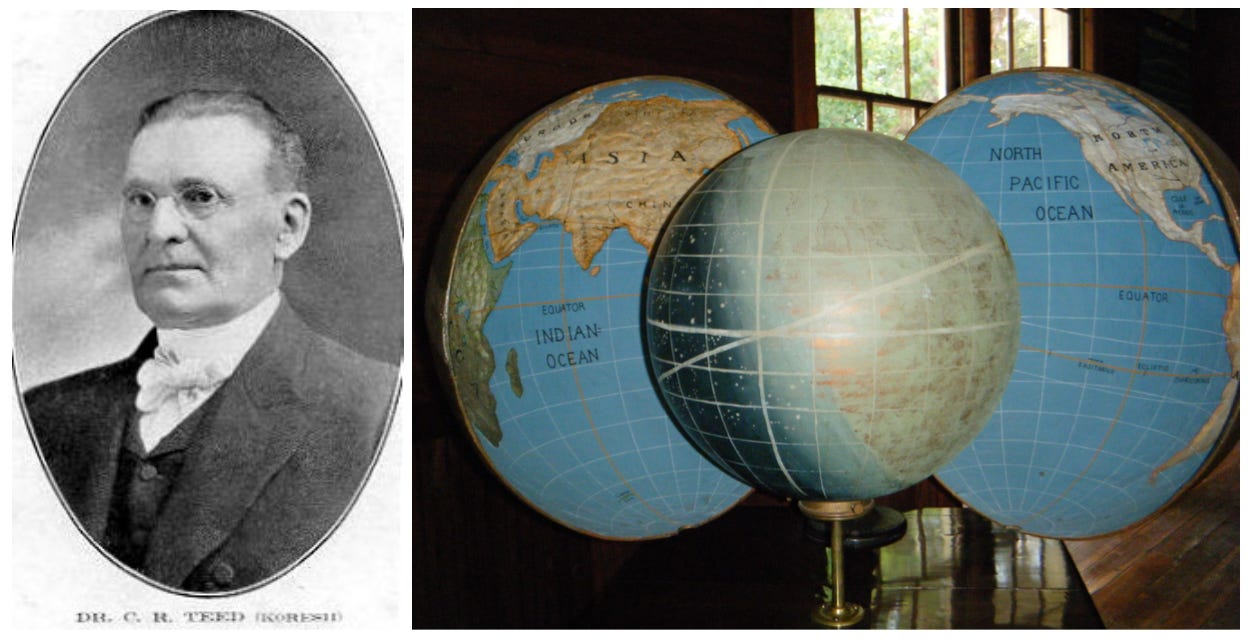

When he wasn’t busy dabbling in alchemy, Teed practiced homeopathic medicine outside Utica, with the eventual prospect of helping to run his family’s mop factory, according to his biographer Lyn Millner, author of The Allure of Immortality: An American Cult, a Florida Swamp and a Renegade Prophet. It’s difficult, looking at Cyrus Teed’s beaky, lipless face, to imagine a man that could captivate huge halls, or convince hundreds of people to pledge their lives to the service of his oracular gift.

But soon enough, in that heady era of utopian communities, he had gathered a flock of disciples, most of them women, who had faith in his sweeping visions: Cyrus Teed was the seventh prophet come to mankind, just as Jesus had; his followers were commanded to live in celibacy; the Second Coming was nigh, and would arrive in an riot of violence. He changed his name from Cyrus to the Hebrew, “Koresh”; the faith he built was called “Koreshanity,” and his followers believed they lived inside the earth, which was hollow, and contained the entire cosmos. “We Live Inside” was their slogan and greeting.

Teed told his followers he could grant them immortality. When he died in 1908, they refused to bury him for six days, laying out his corpse in a bathtub and observing his putrescence, certain it was the prelude to a bodily resurrection. As his flesh blackened, they began calling him “Horus,” after the Egyptian falcon-god of divine kingship, whose form is often carved from basalt. When at last they consigned him to his tomb, they did so in the certainty of his rebirth; they interred him close to the sea, near the utopian community they had built in Estero, Florida, having migrated south at his command to what they called their “New Jerusalem.” In 1921, the sea broke over the tomb during a hurricane, and washed his remains into the Gulf of Mexico. The last believer in Koreshanity died in 1974, more than a century after Teed supposedly received the gift of prophecy. His zeal had carried the flock thousands of miles south, where he raised up a community in the swampland, and convinced his followers that they would live eternally in a paradise deep inside the earth.

Teed may seem a strange bird in the history of American prophecy, but he was hardly the first seer to grace this country’s soil, and far from the last. It takes, perhaps, a remarkable personality to declare oneself a prophet: one capable of either boundless cynicism or fanatical zeal, and possessed of enough charisma to impel others to believe them touched by the Lord. Even in the Bible, the Prophets have distinctly different characters, legible in their predictions: Ezekiel’s hallucinogenic mania, Jeremiah’s dour scoldings, the salvation Joel offers through earnest prayer. All of them claimed to speak with God’s voice, and this unites them; many others have followed in the path they trod.

The history of this country is speckled with self-proclaimed prophets—From Cyrus Teed to Joseph Smith to William Miller, whose prediction that the Second Coming would fall on October 22, 1844, was so widespread that its failure became known as the “Great Disappointment.” And those are just the ones from upstate New York. In fact, prophets and their flocks have sprung up from Maine to Los Angeles, Florida to Oregon—pseudoscientist utopians like Teed, gurus that led their cults to their deaths, social-media grifters spinning hashtags they limn with the breath of the divine. It’s a daring claim, to speak to and for God. But once it is made, and paired with a silver tongue or a skilled pen, it wakes a seemingly boundless hunger in those who read and listen: the need for God, the need for immortality, the need for a life beyond the bounds of the body.

On Sunday I dreamt of Fortune’s Wheel. It was a hot night, coming on the heels of a string of hot nights, and the air was bursting with moisture and gnats and mosquitos. I woke up still dreaming of her. Fortunae—the swelling goddess of luck, one eye thunderous and the other gentle—turns her wheel with a signature caprice, the limbs of the mighty cast down to dangle with the humble, the humble to rise to the mighty’s place. It’s an ancient image, so old that Tacitus considered it a cliché nearly two thousand years ago. And it shaped the religious and political life of the Middle Ages: in perpetual tension with the notion of divine Providence was an acknowledgement of the vagaries of Fortune, the ill chance that took a baby from the cradle, beggared a lord, and occasionally allowed for strange and unlikely flourishings of chance.

“Fortune’s Wheel,” wrote Barbara Tuchman in A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, “was the prevailing image of the instability of life in an uncertain world. Progress, moral or material, in man or society, was not expected during this life on earth, of which the conditions were fixed. The individual might through this own effort increase in virtue, but betterment of the whole would have to await the Second Coming and the beginning of a new age.” God was inscrutable, and while His return might be predicted, it was not within man’s power to control.

That notion began to change with the Renaissance, as humanists “denounced resigning oneself to chance,” wrote the historian Jackson Lears in Lapham’s Quarterly. “Secular individualists like Machiavelli argued that ingenious men might court Fortuna, adapt to her moods, and ultimately bend her to their will.” Suddenly each man was at the helm of his own wheel, expected to thrust at it until it gave way to prosperity. It was not enough to wait for God to come, or to accept the vagaries of happenstance. It was time to hasten His arrival. By the middle of the nineteenth century, an era of prophets who chivvied their flocks toward the end of days began, and never ended.

As mainstream American Christianity shrinks, the prophetic movement within the evangelical church is growing. “Charismatic Christianity,” the font from which the modern prophets spring, is similar to Pentecostal worship: observing the self-proclaimed prophet Cindy Jacobs give her predictions for 2022, one is struck not only by the zodiacal generalities of her predictions (“good things will come for you”; “the Lord says teamwork is dreamwork”; “the Lord sees greatness in you”) but how similarly the prophet acts to any other preacher in the world of ecstatic Christian worship. She breathes on her congregants, and they fall back as if knocked over by a divine wind; she speaks in tongues; lays her hands on them in benediction, and pants out her predictions in her Texas drawl, her shirt glittering in the megachurch spotlights.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Following in the footsteps of other “prophets”—Hal Lindsey, whose bestseller The Late Great Planet Earth set the Tribulations of Mankind in the 1980s, and televangelist Pat Robertson’s frequent predictions of asteroids that would strike the wicked—the Charismatic prophets claim their authority directly from God. You can see it on the faces of Jacobs’ congregants—a hunger for the divine, a yearning beyond the needs of the body. “They’ve combined multi-level marketing, Pentecostal signs and wonders, and post-millennial optimism to connect directly with millions of spiritual customers,” Bob Smietana wrote of the Charismatics in Christianity Today. There is a certain QVC-ish hucksterism to Jacobs’ prophesies: “The Lord just wants you to know that He is going to give you solutions,” she wrote in June. “There are solutions coming for you.”

Despite her seemingly benign prognostications, Jacobs’ influence is leveled directly towards political ends. When Roe v. Wade was overturned, she wrote, “I prophesied twenty years ago that one day a memorial to the holocaust of the unborn children would be built on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and that will happen!” In 2016, several influential members of Morningstar Ministries, a charismatic organization of which she was a member, prophesied that Trump would win the Presidency; Lance Wallnau, a Charismatic prophet, wrote a book entitled God’s Chaos Candidate in which he called Trump a “rugged voice from the wilderness” who would save America from its “fourth crucible” of violent turmoil. A common belief in Charismatic circles about Trump was that he would restore Israel to peace under Jewish control, expediting the Second Coming and the end of days. In so doing, he would become like the king once fulsomely praised by the prophet Isaiah: he would become Koresh.

By 2020, the prophets were no longer content to merely prognosticate: they began to march. The “Jericho Marches”—in which participants rallied against the certification of the presidential election results, in which Trump lost convincingly—were organized by prophets like Jill Noble, whose “apostolic” visions predict an imminent apocalypse. “We are in the days that the early church longed to see,” she wrote on July 11. “There is a remnant of Believers who refuse to align with the Babylonian system. This company of passionate whole-hearted lovers of God will be small in number and will demonstrate supernatural power.”

The Jericho Marchers were present on January 6th, blowing their ram’s horns, hoping to echo the Book of Joshua: “It shall come to pass, when they make a long blast with the ram’s horn, and when you hear the sound of the trumpet, that all the people shall shout with a great shout; then the wall of the city will fall down flat.” In Joshua, it indeed came to pass: the wall of Jericho fell. “And they utterly destroyed all that was in the city, both man and woman, young and old, ox and sheep and donkey, with the edge of the sword.”

Looking into the eyes of those struck by a prophet, you can perceive a ravenous hunger for connection: that the touch of the hand or the breath from the mouth of a charismatic preacher can fill you with the wind of God; that you are not alone in the universe; that you and the rest of the flock can shore up an island of sanctuary for yourselves, and watch in comfort as the world drowns. It is the hunger to be among the elect, and to be immortal, to be one with the Divine, and to welcome the end times. It is the hunger to turn Fortune’s Wheel with your own hands to your own ends, to guide its revolutions, to cast down the capricious goddess and lift up the prophet in his certainty and zeal.

The prophets of America combine prediction with action, whether to scour the country clean of all enemies and set Jesus at the country’s helm, or to create a paradise in a hollow earth. The hunger for the divine certainty they represent can lead hundreds to trek from Moravia, New York to Estero, Florida, raise up a village, build a great tomb by the sea for the man they thought would never die. It can lead thousands into revolt or riot; it can lead millions into cruelties unfathomable to those untouched by gods or prophesies. In my dream, the goddess of fortune, with her mismatched eyes, was neither cruel nor kind; her hands were large and capable as she spun and spun the turning wheel. When I woke up, the dream dissolved into the hot night, and left me hungry.

I have to say this whole area fascinates me -- an atheist -- because I just don't understand the "hunger" these people have. Is it something missing in their lives that causes this hunger? Is it a personality trait? Why are these people so "hungry" that they will follow charlatans along such dark paths?

As a child, I was sent to a religious school (my parents didn't know -- they just picked the "best" school that I could get into) and we had compulsory morning assembly and prayer and hymns, and compulsory religious education (for four years out of the seven I was at grammar school). There were also compulsory after-school events -- Christian rock bands would come and play, and we'd all have to stay late and listen to their dreadful songs. And nearly all my peers seemed to love all of this... and I just found it bewildering.

And now I'm sixty and I still find religion absolutely bewildering. I just don't understand why these people believe in the "old man in the sky" -- and why they feel the need to do such terrible things "in his name".