Welcome back to Culture Club, a feature where David and I write about what we’ve been reading, watching, playing, and listening to, for paid subscribers. Please enjoy this free preview, and consider upgrading to support two struggling journalists at once! — Talia

In an age of such yawning division in the world, any event that can bring us together should be celebrated. The passing of Dr. Henry Kissinger is such an occasion. The response on Twitter was positively Munchkin-like: Ding Dong the Witch is Dead.

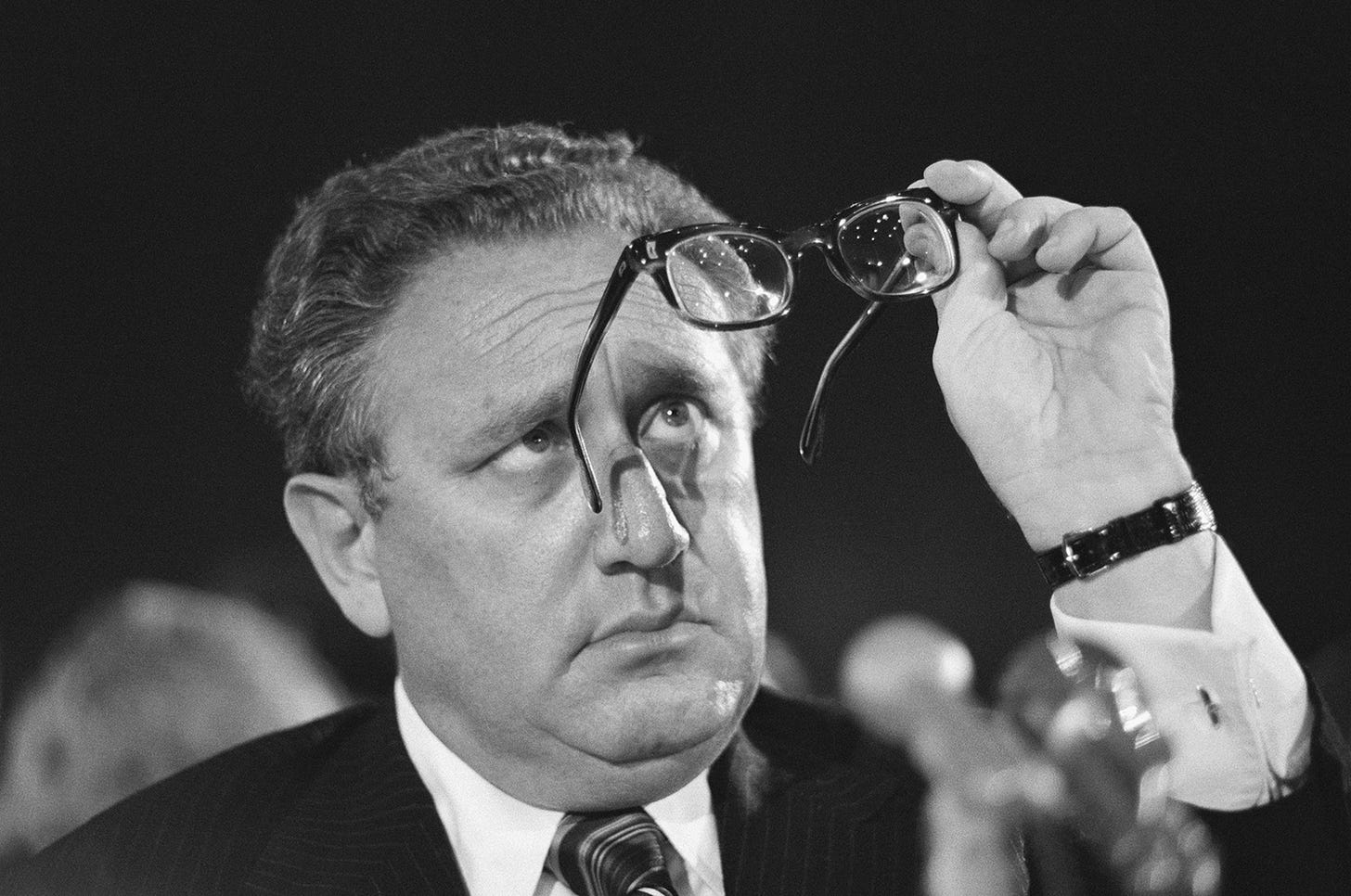

By the time he (finally) died last week, Kissinger had packed a lot into his 100 years: he was an immigrant and an academic, a statesman and a stickman, a Nobel-winner and a war criminal, responsible for the deaths of millions. “He was a murderer on every continent, except Antarctica,” according to Talia. “And people curse his name on every continent, including Antarctica.”

How did Heinz Alfred Kissinger go from promising young intellectual to one of the most malignant forces of the last half century? To help understand this blood-soaked performance, I went through decades of archival material. As illustrated by these selections—from his early papers and books as an author, through the media celebrations and condemnations of his White House tenure, onto dishy accounts of his dating life in New York and hijinks at Bohemian Grove, and, ultimately, his well-earned 21st-century degradation at the hands of Christopher Hitchens and Anthony Bourdain—the story of Kissinger’s career is also a history of the dark side of American foreign policy.

In 2001’s The Trial of Henry Kissinger, Christopher Hitchens’s exhaustive case for the former statesman to be tried (and treated) as a war criminal, the litany of misdeeds is staggering. “These are not, as is too often argued, the results of geopolitical forces for which no one is to blame,” wrote Hitchens. “They are crimes for which Henry Kissinger is, and should be held, responsible, and they vividly insist on an accounting.” Kissinger lasted another twenty two years, of course, with no real accountability. And his dark influence continues to pervade our politics:

Despite living to 100, Kissinger never had to return his Nobel Peace Prize or face his victims in a courtroom in The Hague. But while he lived out the end of his life still revered by the ruling class, he died despised by the world at large. That’s some comfort. He may have escaped legal responsibility for the damage he wrought, but he couldn’t escape disgrace.

Before we descend down the rabbit hole, I’ll leave you with this, from Talia:

“The Hebrew imprecation yimakh shimo, may his name be erased, is the first and worst of all our many curses. In Kissinger's case, I wish for him a fulfillment of Marc Antony's eulogy for Caesar: the evil that men do lives after them, the good is oft interred with their bones. Threading delicate political lines, Shakespeare's Marc Antony goes on to covertly laud Caesar's ambition, and praise his greatness: ‘No such restriction is imposed on us, neither in gratitude nor restraint.’ I wish not for Kissinger's name to be erased, but his good name interred with his bones, and only the manifold cruelties he performed be synonymous with his person. It was an august personage too long; let that patina of respectability be erased, and let him take his place among history's malefactors.”

Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy

By Henry Kissinger

Council on Foreign Relations, 1957

In Greek mythology, the gods sometimes punished man by fulfilling his wishes too completely. It has remained for the nuclear age to experience the full irony of this penalty. Throughout history, humanity has suffered from a shortage of power and has concentrated all its efforts on developing new sources and special applications of it. It would have seemed unbelievable even fifty years ago that there could ever be an excess of power, that everything would depend on the ability to use it subtly and with discrimination.

Yet this is precisely the challenge of the nuclear age.

Ever since the end of the second World War brought us not the peace we sought so earnestly, but an uneasy armistice, we have responded by what can best be described as a flight into technology: by devising ever more fearful weapons. The more powerful the weapons, however, the greater becomes the reluctance to use them.

Letter from Washington

By Richard H. Rovere

The New Yorker, January 13, 1961

The new administration takes office at the onset of the “missile gap”—a theory, a condition, a predicament, and a state of mind that is expected to prevail for not less than the four years that John F. Kennedy has been elected to serve. “The missile gap in the period 1961-65 is now unavoidable,” Henry A. Kissinger, probably our most influential critic of military and foreign policy, writes in “The Necessity for Choice,” to be published by Harper next week. His book, an all but encyclopedic review of the current problems of American security and diplomacy, will almost certainly be used as a basic text by some makers of policy in the period ahead. For the next four years, Mr. Kissinger says flatly, “the Soviet Union will possess more missiles than the United States,” and he maintains that this numerical superiority is a crucial and potentially decisive one. It brings to at least a temporary end the “nuclear stalemate” that has so often been described over the past decade as the principal deterrent to war. There is no longer a “balance of terror” between the great powers. There plenty of terror in the world, but it is far out of balance, and it can no longer be relied upon to deter the Soviet Union.

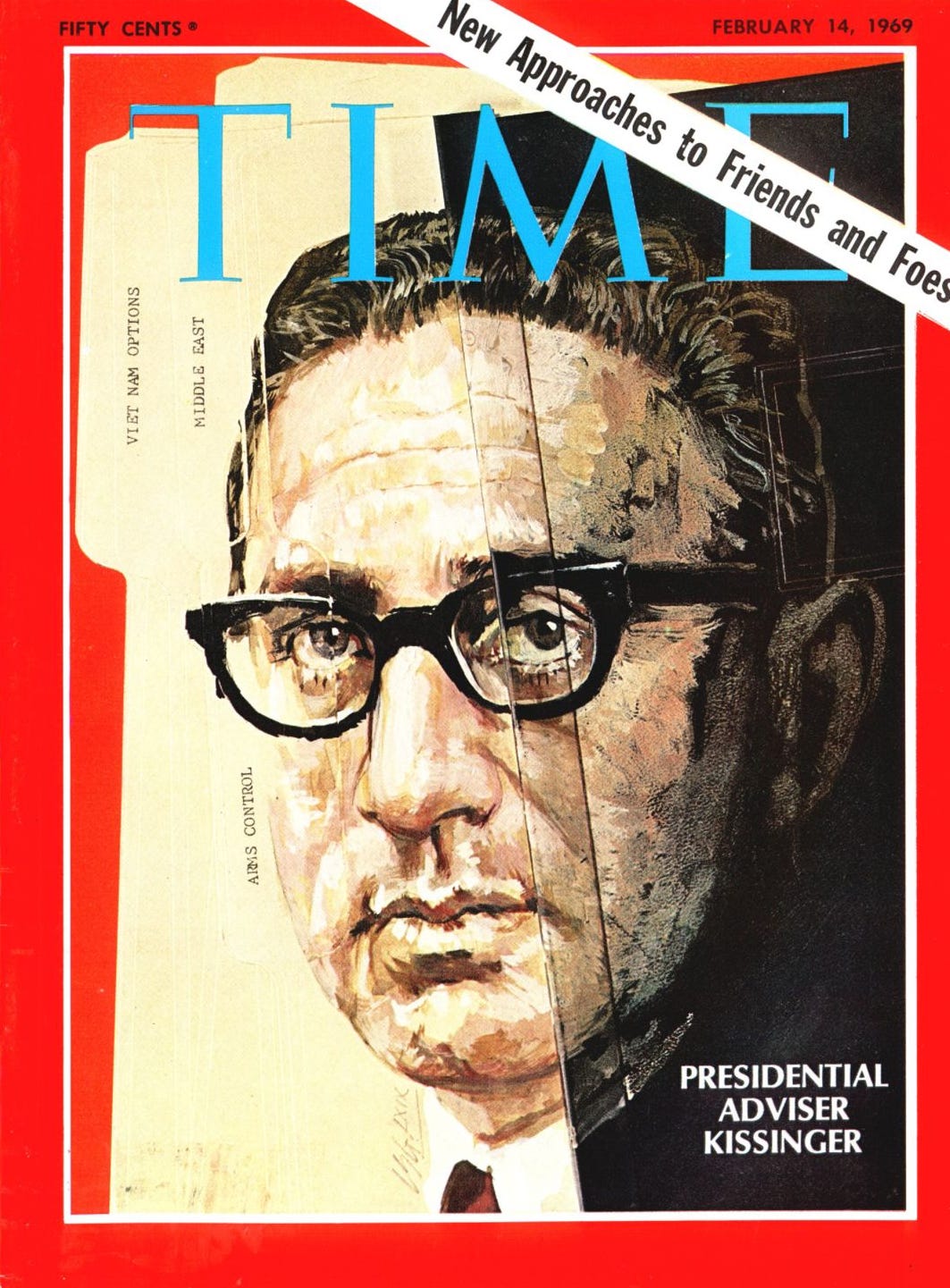

Kissinger: The Uses and Limits of Power

Time, February 14, 1969

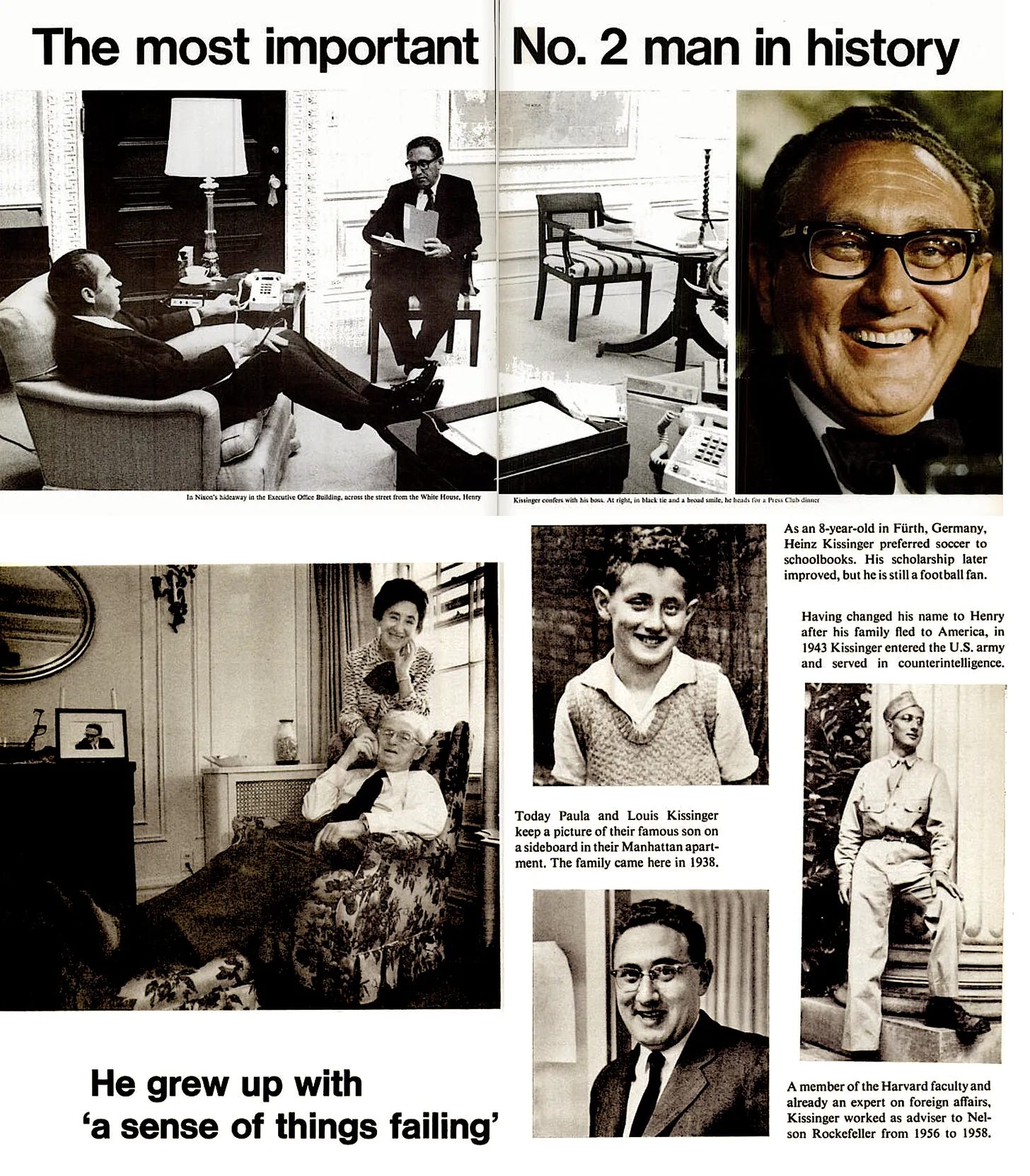

In the German city of Fürth, in Middle Franconia, few people remember the Kissingers. Before World War II, Henry Kissinger's father Louis, now 82 and living in Manhattan with his wife Paula, was a respected Studienrat, or high school teacher. The family enjoyed a middle-class life: a five-room flat, many books, a servant and a piano, which young Heinz avoided practicing whenever possible. He preferred soccer.

When the Nazis gained power, life became difficult and dangerous. “The other children would beat us up,” Henry recalls now. His father was forced to retire, but thought that the madness would pass and tried to wait it out. Finally the pressure became too much. Concerned that Heinz and a younger brother, Walter, would not get a proper education, Louis Kissinger took his family to America in 1938.

The father did not have an easy time in New York. Unable to get a teaching post, he wound up working in an office. To this day, his heart is in Fürth. He has been back to visit twice, and two weeks ago wrote to the local newspaper to ask for clippings of stories about his son. Heinz, who soon became Henry, adapted much more easily. In Germany, he had been an average student. In Manhattan's George Washington High School, he became a straight-A pupil.

The Road to Peking, or, How Does This Kissinger Do It?

By Barnard Law Collier

New York Times, November 14, 1971

Some of Dr. Kissinger's old colleagues and acquaintances, free from the passion of topical debate, ask themselves, and each other, “What is it that Henry wants?” Does he want to be known as the most significant German‐Jewish immigrant to America since Einstein? Does he want a share of one of those symbiotic relationships of history—to be remembered as Nixon's Kissinger? Does Henry truly have an epic vision of history?

“I believe,” Henry Kissinger says, “in the tragic element of history. I believe there is the tragedy of a man who works very hard and never gets what he wants. And then I believe there is the even more bitter tragedy of a man who finally gets what he wants and finds out that he doesn't want it.”

The Most Important No. 2 Man in History

By Hugh Sidey

LIFE, February 11, 1972

With the lone exception of Richard Nixon, who is 50 paces down the hall and already deep into the morning's routine, Kissinger is the most talked about, most analyzed and most important man in Washington. There is not a No. 2 man in history who has ever wielded such power, with such authority.

He has devoured his dietary portion of scrambled eggs, crunched through half an English muffin and now is pouring black coffee. He has read hastily through the cover stories on him in both TIME and Newsweek. After a few caustic comments about how journalists think the National Security Council works, he grins and says, “I asked [White House speechwriter] Bill Safire if he thought I could survive two cover stories in a single week. Safire said, ‘No, Henry, but what a way to go.’”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sword and the Sandwich to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.