Starving for Jesus

The docuseries “The Way Down" on HBO Max glibly examines the horrifying nexus of diet culture and fundamentalist Christianity.

Programming Note: For the first two weeks of this newsletter, in order to grow my audience and make as many people as possible aware that it exists, I’ve been publishing on a five-days-a-week schedule. Mercifully for both my sanity and your inbox, next week I will switch to a twice (and occasionally thrice) per week schedule, which is much more manageable! OK, on to the content.

This weekend, driven by a personal and professional curiosity about authoritarian Christianity’s various flavors, I fired up HBO Max’s new three-part docuseries The Way Down: Greed, God and the Cult of Gwen Shamblin. The documentary follows Shamblin, a charismatic preacher-cum-weight loss guru, from her girlhood in the overtly misogynistic Church of Christ to her ascension as a leading light in Bible-themed weight loss workshops in the 1980s. After her “Weigh Down” pray-yourself-thin mantra sparked fawning mainstream-press coverage (she reportedly played her interview with Larry King Live on loop in her home) and spread to thousands of churches, Shamblin took a step further and founded her own in 1999: the Remnant Fellowship Church, a Brentwood, Tennessee-based congregation that focused on, among other things, getting thinner so God will love you more.

Shamblin died last year in a plane crash, along with her husband and five other leaders in Remnant Fellowship, towards the end of the documentary’s filming — a fact that hangs awkwardly over the three released episodes, and has spurred the promised release of two additional ones next year. Apparently, a lot more people were willing to open up about Shamblin and her church after she was dead. That speaks to her influence, and the church’s litigiousness, and perhaps even the ways her theology postulated that the way you looked and your fortunes in life were direct reflections of God’s favor.

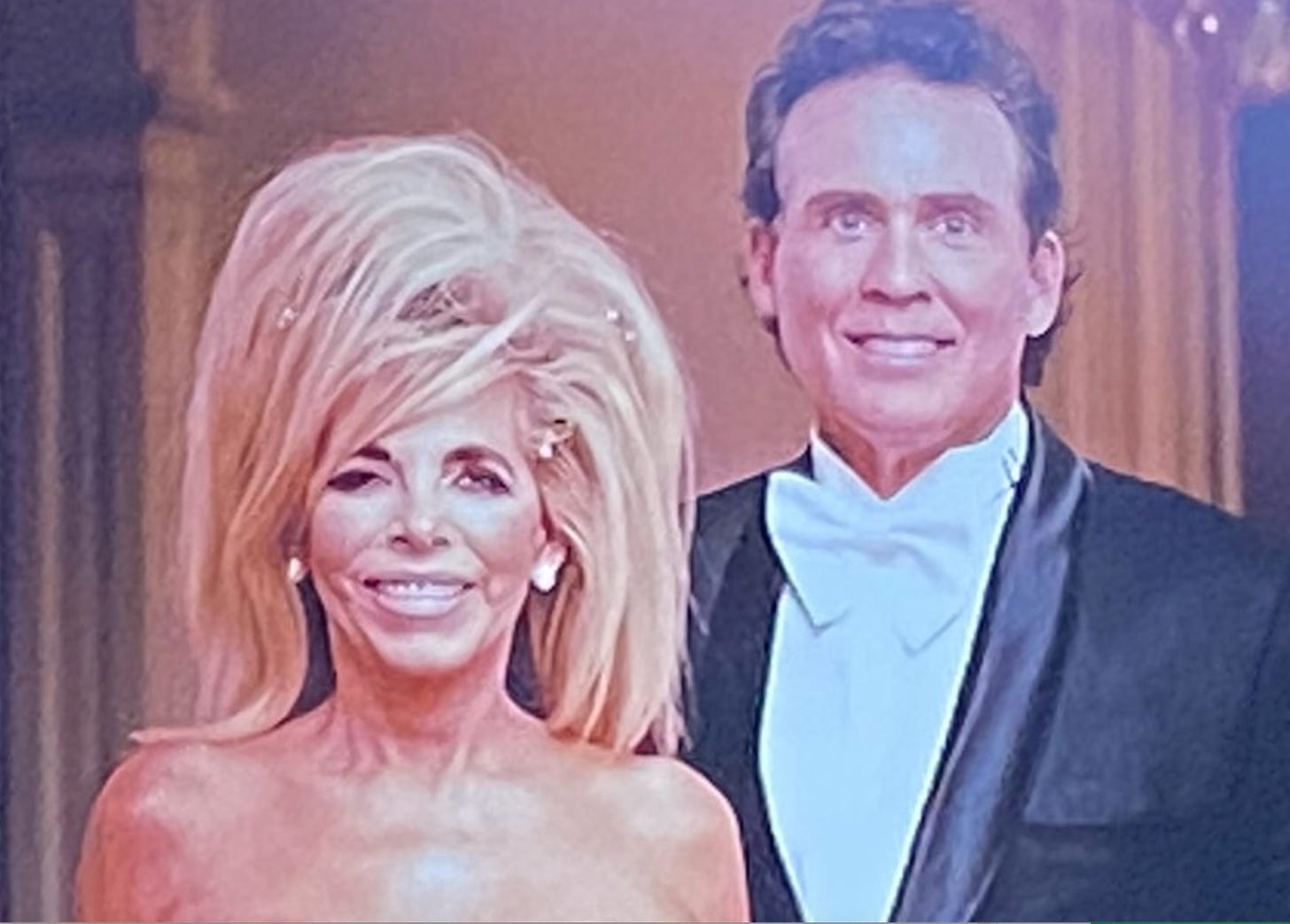

The result is compelling — the documentary is hard to watch and harder to stop watching, and I completed all three episodes in a single night — but ultimately facile, in ways that are deeply frustrating. In some respects the story is a perfect fit for a visual medium: Shamblin’s personal transformation is astonishing to watch. Onscreen, she goes from a modest ‘80s church lady with a sensible bob, to a spiritual leader-slash-prophet with a towering, complex blonde edifice of hair (as one former parishioner put it, “it’s gotten taller every year she’s been there”), teetering heels and skeletal limbs. On a similar note of visual grotesquerie, Shamblin’s second husband Joe Lara — a former actor whose leonine, muscled good looks earned him stints in such films as Tarzan in Manhattan, and who is the chief subject of the second episode — appears to be a cautionary tale about the transformative effects of cosmetic surgery. Together, the reigning couple basked in their own self-defined beauty — while tormenting a parish of thousands.

It’s in documenting this torment that the film stumbles, repeatedly. The filmmakers give viewers some details of Remnant Fellowship that seem both awful and particular to that church — former parishioners describe being coerced into fasting for weight loss, sometimes for 40 days at a time; Shamblin’s theology is explained, with brutal simplicity, as a doctrine that declares thinness closer to God. Even before she founded the Church, her Weigh Down Workshops encouraged their mostly-female audiences to refrain from eating until they felt actual pain from hunger; church attendees were required to be enrolled in such workshops at all times. Shamblin is shown on camera repeatedly holding up Nazi concentration camps as a favorable example of weight-loss techniques (“When people were in prison camps and ate less food, they lost weight.”) But her divorce after decades of marriage (her first husband was overweight), her children’s enigmatic psyches (particularly a son, Michael, who appears to have struggled in his role as a pillar of the weight-loss church), and the tabloid spectacle of her second marriage to a younger man are given equal weight and significantly more screentime than other, more serious issues — including murder.

The third episode is partially devoted to the ways in which Remnant Fellowship Church sanctioned and encouraged corporal punishment of children, with fatal results. Joseph and Sonya Smith, loyal members who appear in lots of worship footage, were convicted of battering their 8-year-old son to death in 2007. According to the documentary, they confined him in a wicker box, slammed the lid on his head, and secured the box with bungee cords until the child died of a combination of blunt trauma and suffocation. Later, tapes surfaced of Sonya Smith calling in to a consultation session in which Gwen Shamblin praised her harsh parenting. The church paid for defense lawyers for the couple, and, after the conviction, solicited donations for appeals through a website it created, entitled “The Smiths Are Innocent.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Far from any apology, Shamblin and church elders continued to embrace corporal punishment after this tragedy; multiple former parishioners testify on camera about being instructed to spank their children “up to 30 times,” to use switches or long hot-glue sticks to beat their children. Church elders are also described as administering corporal punishment to parishioners’ children — Gwen’s right-hand man, who bears the improbable name of Tedd Anger, is accused of beating a boy with his belt “more times than [he] could count.” Having dispensed with murder and abuse in about 20 minutes, however, the documentary seamlessly flips to discussing other elements of the church’s culture. (By contrast, Gwen’s second marriage is given nearly a full hour.) The treatment of this grave a subject feels perfunctory — and, given that the Smiths and their murdered child were among the few Black members of the church, inadequate. How did race play into the way these events unfolded? Why did the Smiths join the church in the first place? These and other questions remain unanswered.

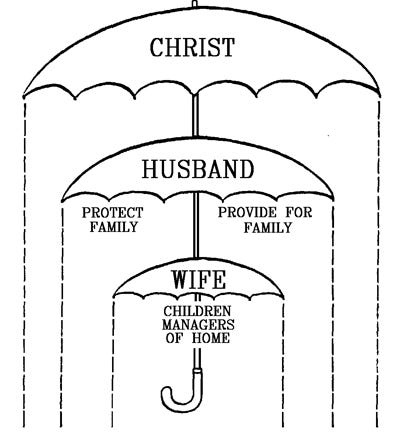

What’s more, several aspects of Remnant Fellowship’s theology — its draconian approach to child punishment and “Total Obedience,” and its unrelenting misogyny, in which women were coerced to submit to their husbands and remain in abusive marriages — are presented as unique pathologies of Shamblin’s religious empire. But anyone with even a perfunctory knowledge of evangelical culture knows this is far from the truth. Misogyny is ubiquitous in fundamentalist communities, whose Bible-inspired philosophy maintains that the proper role of a woman is absolute submission to her husband’s authority. Divorce stigma keeps women in abusive marriages; a doctrine of submission means that popular Christian marriage advice books advocate for women to have sex with their husbands when they don’t want to, or risk God’s wrath. A worldview in which a man’s “headship” — dominion over his family — is depicted as absolute, divine, and unquestionable is one in which women by definition cannot be equal, and it is a worldview shared by millions in the United States.

The “Umbrella of Protection,” an image created by Bill Gothard, a titan of Christian homeschooling whose curricula are still in use — and who was disgraced after a decades-spanning scandal involving him sexually abusing young girls. “We are responsible to submit to these authorities in order to receive their protection and the blessings of living in submission to God’s authority,” Gothard wrote.

Training children towards absolute obedience, often through corporal punishment, as a means to draw them closer to God is also not unique to the Remnant Fellowship Church. Far from it. The 1994 blockbuster book To Train Up A Child, written by Michael and Debi Pearl and distributed through their organization No Greater Joy Ministries, has sold more than a million copies. The book advocates for beating, confining, and starving children until their will is “broken” into Godly obedience. (The first chapter alone compares children to rats, dogs and horses; promotes “training sessions” that involve striking children as soon as they are able to crawl; recommends pulling the hair of nursing infants who bite; and striking the bare legs of a five-month-old who had become curious about crawling up the stairs with a twelve-inch willow switch.) The book has been linked to at least three deaths of home-schooled Christian children, including 13-year-old Hana-Grace Williams, whose parents were devoted students of the Pearls and who died of hypothermia and malnutrition in 2011, emaciated, naked and alone in the mud after being locked out of the house as punishment in 40-degree weather. To Train Up A Child remains in circulation, with an updated version — which still contains chapters titled “The Rod,” “Applying the Rod,” “Philosophy of the Rod,” and “Religious Whips” — released in 2015.

Suffice it to say that Shamblin was not alone in advocating for a doctrine of total obedience enforced by physical punishment; she was not even, particularly, an outlier in fundamentalist culture. There are a few male critics in the documentary who speak from a Christian perspective. They do not critique the church’s approach to family relationships or to child abuse; they critique Shamblin for her vainglory, her appearance, her ambition, her usurpation, in their view, of the place of God. It’s not any of the particular doctrines of Remnant that they find objectionable — not the starvation or the beatings or the endless submission; it is Shamblin’s ostentatious leadership, or perhaps that a woman led a church at all.

Ultimately, The Way Down is a glib, if ghastly, look at one woman’s quest to turn as many other women as possible into starved, passive vessels of faith. It neglects to contextualize Shamblin in the broader milieu of American fundamentalist Christianity; leaps nimbly from horror to horror without sufficient examination; and refrains from exploring the media’s role in rocketing her to stardom. Perhaps these issues will be delved into at greater — or any — depth in the subsequent installments of the series. But I’m not optimistic that the filmmakers will rise to the giddy heights of Shamblin’s hairdo, let alone to the occasion.

I saw your comments on Twitter last night and then after reading this I feel awful. The stuff about beating children is awful to think about and brings me to tears.

Amazing how there's scientific evidence of the real harms of hitting kids, but a segment of the population doesn't care. I wonder how many of those same people think abortion is murder and should be illegal?

Thank you, Talia, for shining a light on this. I grew up in a similar toxic fundie culture and at age 46 I am still coming to terms with how much my parents damaged me. Over the years I've tried to have a good relationship with them, but it's so hard when i'm told "we were doing what we thought was best" and other minimizing handwaving. To know that others see the pure misogyny and physical abuse of that culture for what it is, is very cathartic.