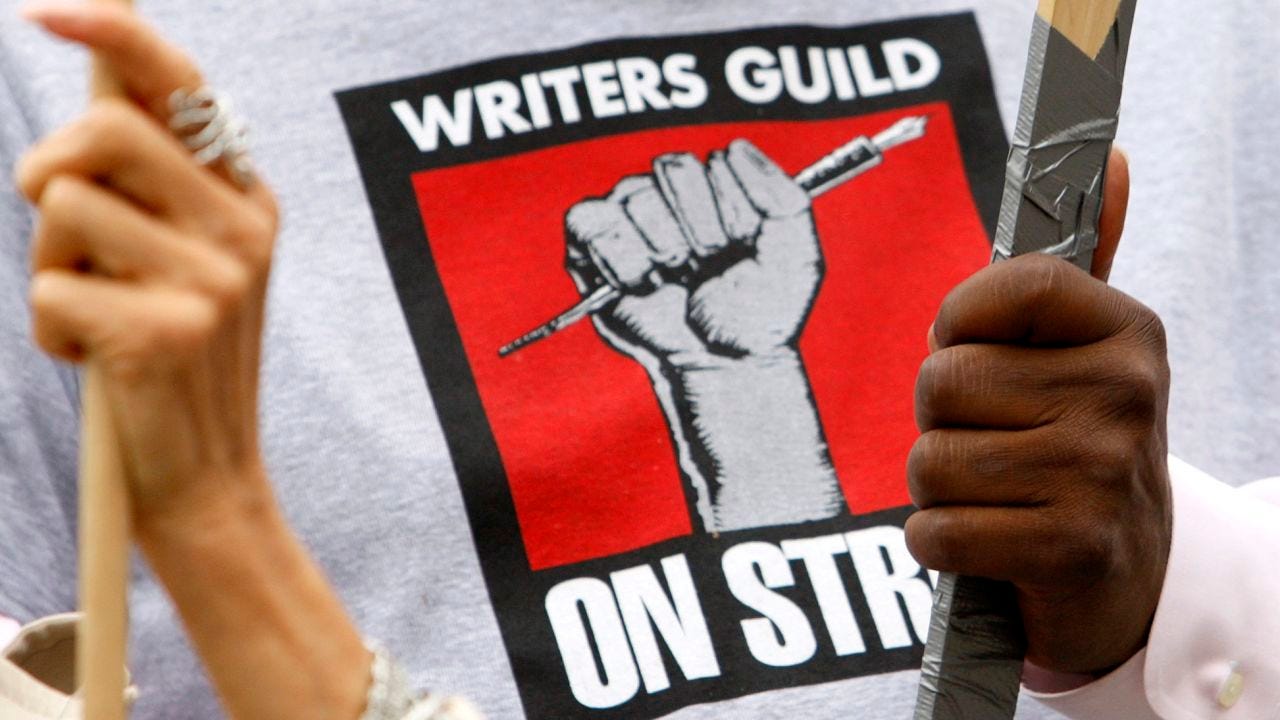

Strike! Strike! Writer's Strike!

We're back, and the WGA is striking for just labor protections.

Author’s note: Hello ladies, gents and gentlethems! After the past week’s much-needed breather I am back on the horse—the horse of writing—the workhorse—measuring the knobs on its wasted spine, urging it into a jerky canter on a rutted road, et cetera. I’m hoping this onrush of metaphor operates like sleight of hand concealing the poverty of the hand itself and that it is outstretched towards your pocket. I’ve spent the past week—for which I thank you again for your indulgence in not unsubscribing—in a bad-meds-induced bramble patch in my head. On the plus side all the rage and terror seemed to key me in a bit better to the national mood, which is all homicide of neighbors and intractable institutional rot; on the minus side, well, it’s an awful way of being. I’m hoping I’m on the upswing now, though, or at least muddling along, and making my deliveries. Excelsior…

It’s the day after May Day, and one of the most visible unions in the country, the Writer’s Guild of America, is on strike! I say this without undue glee—it’s always workers getting fucked over relentlessly that leads to this sort of situation—but with a surfeit of comradely brio. Yesterday in Paris, where protests against the shrinking of the social safety net are ongoing, workers were throwing Molotov cocktails down the broad boulevards; today, writers in the U.S. are striking for a principle that has become degraded past the point of bearing: that writing is labor, and labor deserves just compensation.

Suffice it to say I’m fully in the corner of the WGA, here. If you want to know a little more about what’s motivating the Guild, check out this chronicle of the barely-subsistence-level wages provided to TV writers, and the pretty much unlivable conditions it takes to earn them. TV writers deserve a whole lot better than the raw deal they’ve been getting, and just because the job sounds, from the outside, glamorous and lucrative, doesn’t mean it actually is. The late-night shows are shutting down til this is over; the effortless hum of well-turned palaver from the handsome faces on the screens is powering down, until the people that wrote those words get the good that’s coming to them.

Not without a little bit of self-interest, I will say that I think writing as a general profession should offer a middle-class and survivable life. If you don’t think so, try Googling for any bit of useful information (when should I plant carrots? how do you put together this toaster?) and wading through the ocean of machine-generated, ad-supported sludge it dishes up. You’ll want to tear your hair out at the roots.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Too much exposure to machine-generated prose has a corrosive effect; there’s no guarantee of trustworthiness, and no stamp or quirk or generative hint of id; it’s a subtle irritant, a smooth stream of mild acid over the whole of the body at once. Enough of it and you face a silent dousing in the inhuman: alienation from the self and others.

Not incidentally, one of the sticking points between the WGA and management groups was a clause ensuring that shows would not be written using AI, and that union-written material would not be used to train scripted machine-learning. In other words: don’t use our shit to perfect our robotic replacements. Fuck you, said the studios. So the strike is on.

For contrast to the rotten deal on offer, and in consideration of the riper things we could have, I’d like you to think of a moment in time when you have encountered a perfect sentence, or a perfectly written and perfectly delivered line in a movie or a TV show. A time when you’ve swirled a phrase around in your mind and mouth and let it rearrange your inner furniture.

For what it’s worth, here’s one of mine, hidden away in an inner corner, one of the reasons I still live in New York City—a colossus of a sentence by Saul Bellow I ran headfirst into as a teenager:

On Broadway it was still bright afternoon and the gassy air was almost motionless under the leaden spokes of sunlight, and sawdust footprints lay about the door¬ ways of butcher shops and fruit stores. And the great, great crowd, the inexhaustible current of millions of every race and kind pouring out, pressing round, of every age, of every genius, possessors of every human secret, antique and future, in every face the refinement of one particular motive or essence—I labor, I spend, I strive, I design, I love, I cling, I uphold, I give way, I envy, I long, I scorn, I die, I hide, I want. Faster, much faster than any man could make the tally. The sidewalks were wider than any causeway; the street itself was immense, and it quaked and gleamed and it seemed to Wilhelm to throb at the last limit of endurance.

The lines I love in TV differ a little from this kind of showpiece of a sentence: they tend to be culminations of situations, parabolic heights to character arcs, or asides that are best viewed in context, not isolation. Boardwalk Empire’s quip-cum-tagline—“You can’t be half a gangster”—has become something of a life motto, though, and I still wonder, like Tracy Jordan, why pigeons eat out of the trash. Don’t they know they can fly? I know there’s always money in the banana stand, that alcohol is the cause of and solution to all life’s problems, that if you come at the king, you best not miss: and my life is richer for that mosaic of stories, carefully sketched out in script form, just as carefully realized onscreen, and sticking with me for the foreseeable future.

Moments like that, where a writer climbs into your head and makes a perch there for the rest of your life: they’re worth living for—and because our lives are mediated by capitalism, therefore they are worth paying for. Consider sitting in inner silence forever, without anyone else’s words—without anyone else’s dreams or conjectures or jokes, from any other time, from any other place—to salt and pepper the situation. It’s a horrifying notion, isn’t it? Anything you might want to say about self-reliance or stiff-upper-lippedness wilts in the face of truly protracted inner silence. Without the words of others, who are we?

Writing is how we communicate with the past, and how we arrange ourselves in the most flattering light for posterity. Without it a great chain linking you and me to Ptolemy and Josephus and the ancient Sumerians breaks. Over a great distance of time a shattering of styluses, a sundering of tablets. Even back then, they paid their scribes, and they wrote about the gods’ wars and their lovemaking.

The best things you’ve ever loved had a soul feeding them, or a roomful of souls, and all the accumulation of experience that enabled those souls to siphon pieces of themselves for your benefit. Even the crappiest shows and films and books you’ve ever loved had a human heart behind the words. And the people who write the things you love should be able to live and live decently. The thing about writing is that, well, Res ipsa loquitur. All you have to do is listen. And join the picket line.

In short: damn the torpedoes. Fuck the machines and the metaphorical machine of the studios and their Wall Street backers and the hollow false doctrine of endless growth—that profit isn’t sufficient, that everything needs to be squeezed to the last blood cell, carved to bone shards, skeletonized for every flesh-strip of profit. That everything needs to be hollow, Potemkinized, including the wallets of those few laborers deigned to be hired. Fuck this bloat and this greed. You can make good things and still make good. You don’t have to shovel human lives into the mouth of a stock-market bull-god. None of this is inevitable; insatiable greed is as much a choice as anything else. Tweak the fucking graph so people can live. Or they’ll flood out to the streets and let the world know what you’re up to.

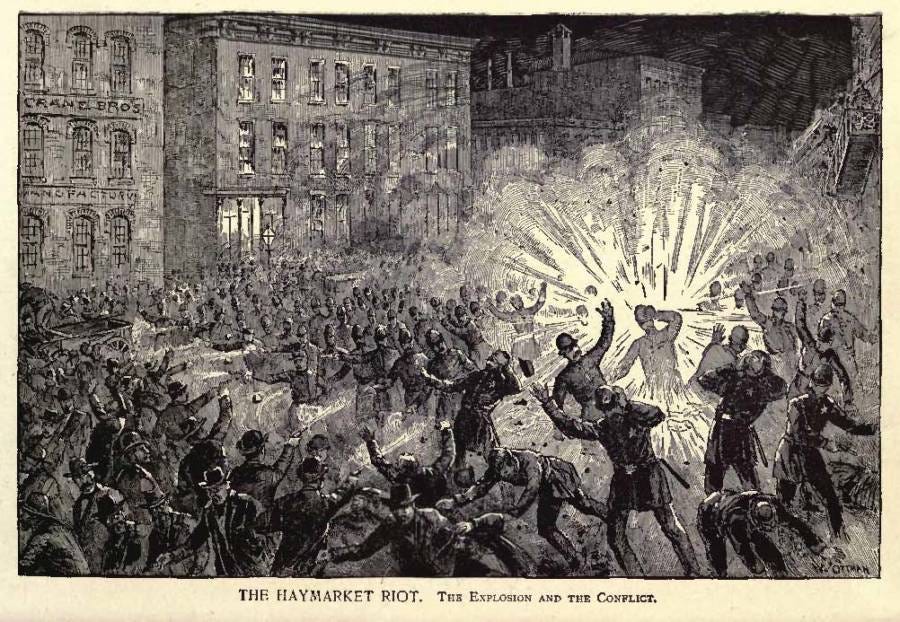

A ceaseless rain that flooded parks and highways let up finally on May Day; the day of the Haymarket Riots whose martyrs’ blood still cries out from the earth; the day that gave us the full glory of Emma Goldman and the reality of the weekend; the day the poet Voltairine de Cleyre said was “written in red” … This is the day I wrote to you, to myself, to everyone, to tell you that the human endeavor of shaping words, passed to me from Sappho, passed to me from Basho, from Turgenev, from Isaac Babel—is labor—and deserves everything.

Or to return to Saul Bellow’s wretched narrator Tommy Wilhelm, on the single strange inward day cataloged in that novella—

And though the sunlight appeared like a broad tissue its actual weight made him feel like a drunkard.

I write to you drunk on sunlight; I write to you and that in and of itself is a compensation; even if I too need to live on money—it’s worth it to know again in all my big and little bones and boiling brain that I won’t stop writing til I die.

"I won’t stop writing til I die".

Indeed.

And even then I'll leave behind a thousand unwritten things.

People need to eat and have homes and stuff. No job should pay so awfully that it doesn't allow for that. Or for self care.

I can't count the sheer number of writers in every medium that have spoken their words into my head and my heart. We can't stop, but we also need to live in the real world.

Great piece, thank you. I hope they get what they need.

Thank you!