This is a specific story. A specific small giant has gone, a woman possessed of a certain kind of midcentury glamor that has largely passed from the world, that effortless ethereal combination of postural rigidity, bitten-out syllables and looping Edwardian script that is a vanishing quantity. But there are many holes in the year for many people; parents, siblings, lovers, friends; holidays are people and scents, the choices of the host and their environs. Maybe yours is a carol or a cake or an empty chair. When a gravitational center of your life vanishes you whirl askew around that date, off-kilter—a keeling top, a cracked spindle.

She didn’t want to be mourned. That’s what her son said, but we mourned her anyway, each in our own separate hearts, or we had quiet, private, half-finished conversations about it. Grief has a way of getting out of you even when it has no natural outlet, a pot spitting oil onto skin, a sea-floor tremor. It comes out in abstracted anger or in sudden remembrance and without the disgorging effect of talk it lies in you compacted as a bezoar, and makes you strange.

I am used to the Jewish tradition of shiva where you talk for six days straight about your memories, sitting on the floor in torn clothes, mouth dry with anecdote after anecdote, but she didn’t want that, she was just alive, then ashes. When she died she was eighty-eight, officially in that category of persons rendered non-persons during the pandemic, but all that meant was she had time to mean something to more people—decades of people, and generations, so that teenagers she taught how to drive brought their grandchildren for her approval.

It’s rare that someone is so completely associated with a holiday but I went to her house every year of my life for Thanksgiving bar two, when I was not in the United States; my father went to her house for Thanksgiving for sixty-one years; it was the only time of year I saw my father’s people. Her house was the best-smelling warmest house; on the broad lawn the air was crisp, north of the city you could see the constellations.

The young cousins and I among them slept in a pile in the basement among stored paintings and books and a billiard table, until we grew up and gave way to another generation of cousins, sleeping, interlocked, on the same pallets. Hexagonal red tiles on the floor of the vast kitchen, the big black stove with a perpetual palaver of pans; the bric-a-brac artful; the dogs she chose as puppies for their big paws, who grew gray-furred and died and were mourned and replaced. The last one outlived her and he lies with his paws up begging for a belly-scratch, black muzzle scattered with salt.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

At the turning of the year we would make that trip, crammed in the back of the car, piling out onto the big crowded gravel drive; she would preside, the empress regnant of the party, and the big fireplace would eat its fill and grin red embers. Without her this year, the holiday had a hole—just as the world had a hole—like a knocked-out tooth, and we worried and worried at it, feeling the ridges of the gap, where it was jagged and where it would heal. We spoke around the enormity of her death but the house was full of it.

The house was her son’s now but little outwardly had changed. The lap-sized hardback of France, the Beautiful Cookbook was missing from the bathroom radiator and the fridge was stripped bare of the photos she pinned there and more than reading the trail-signs of her absence there was the fact of it; no small figure with sharp upturned nose who gripped you hard and got bonier each year and drifted between the guests at her own whim; up the precipitous wood stairs her bedroom was empty, her bed still broad, big as a moon when I was a small girl, and strewn always with newspapers.

She died in the summer when her garden was in the full decadence of its blooming. Some of the last conversations we had when she could still write back were about gardening—she was glad I had come to this joy, even if late in life, and could reap “its astonishing benefit to the eye and heart and the mouth!” She died two months after she wrote me that. No funeral; she is tucked in an urn somewhere in her astonishing house full of astonishing things, first editions, odd bronzes, oil portraits of herself black-haired and young and languid; outside, ground-cover of phlox, foxglove, cobblestones. She taught me to use ash from a match applied to a box bottom as eyeshadow.

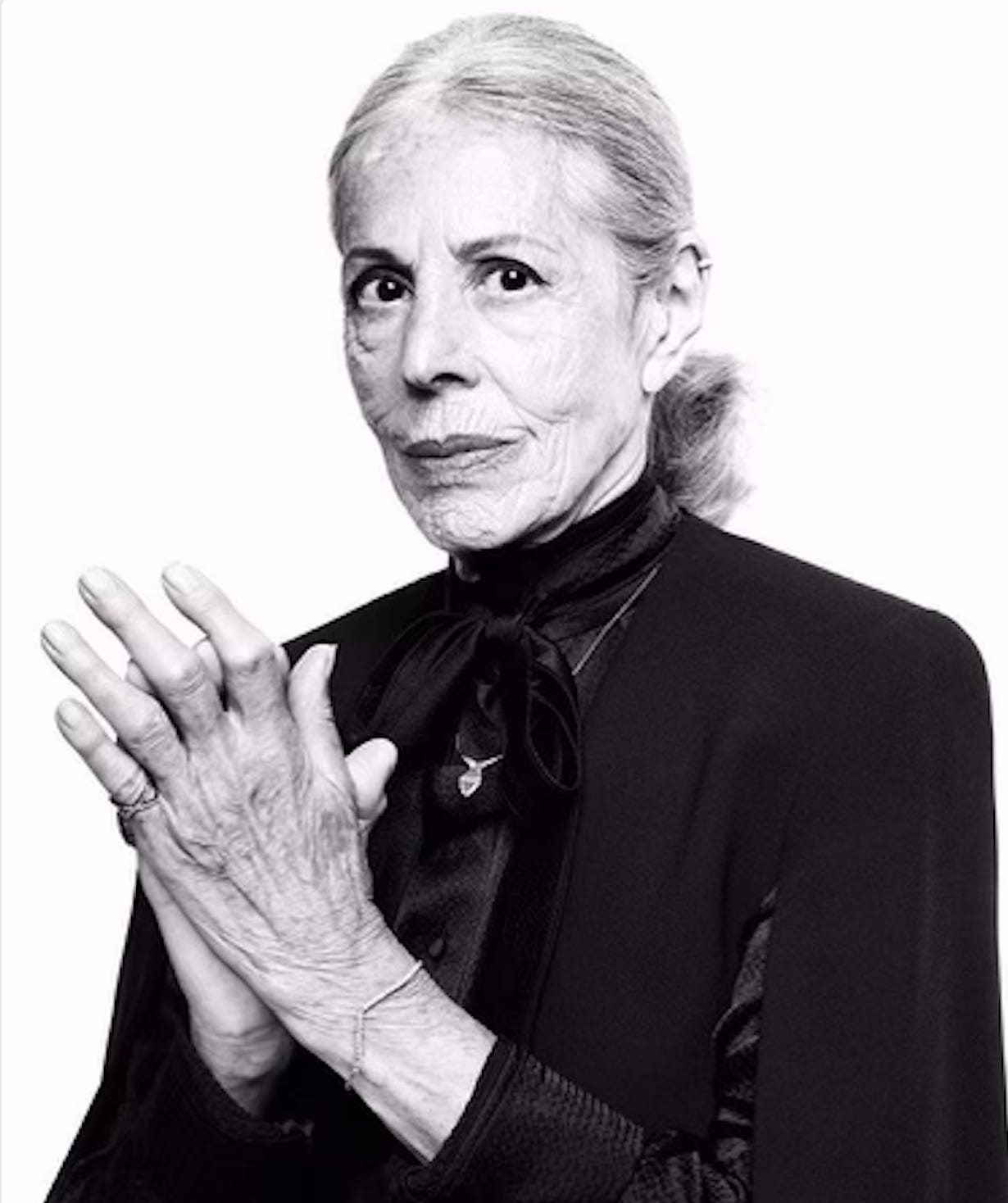

She got an abortion in the 1950s and lay in bed for days and then got up again and went back to work writing for Parade. She was inseparable from Sylvia Plath at Smith College; their decade of letters is severally collected; both a portrait of Plath she took and a photograph taken of her are in the National Portrait Gallery’s collections. A few years before he died, Philip Roth left her a voicemail asking why they’d never fucked. A different famous author I will not name bought her a red sports car and proposed and she turned him down. She spent the millennium on Puff Daddy’s yacht.

And more, and more: She grew tomatoes the size of two bunched fists together; she kept a stable full of miniature donkeys. Her older brother disappeared mysteriously when she was young and she never stopped looking for him. She grew up a Jew in New England in the 1930s and ‘40s and had pennies thrown at her; she loved men and was loved by many but spent most of her adult life alone; she loved her son; at eighty-eight in the interims between hospital stays she would pillow-fight her two-year-old granddaughter with surprising ferocity. I do not know a sixteenth of her stories or a sixtieth, and now I never will.

There will always be a hole in the year; I can give thanks I knew her, but I am petty and grudging about it and would rather she be here, instead, so the gratitude is bitter in my mouth. I sent her all the first drafts I thought were important and I wish I could send her this column. I think of her small body in bed and how in the last months she never stopped being cold. I think about the oddest details: how small and fine her teeth were; how she got bit by a brown recluse spider late into her seventies, bent flush to the earth to weed a bush; the pilly texture of her omnipresent sweaters; how she called me her favorite writer; how her most-used email subject line was “You.”

We spoke about her just once at the end of the evening, and briefly. She didn’t want to be mourned. And in her magnificent house the cream oozed from the cannoli and the fire grayed to ash and children learned chess at the table she chose half a century ago. There are so many holidays like that for so many people: ruts and scars in the year. We grieve and subsume the grief to a trembling underwater. Next year it will come back when the leaves die, and every year after. Her vanishing is part of me now, that black gap is remembrance. I turn to the ungovernable past but it will not give her back.

May her memory always be for a blessing.

Amazingly written. We, unfortunately, had a similar situation at Thanksgiving this year. It was rough as everyone thought about saying something but nobody knew if it was the right thing to do.