The Collectors

On Harlan Crow, the human drive to accumulate, and what it means to own a country

Harlan Crow, as much of America has recently discovered, is a Dallas developer with a comic-book villain name and a suspiciously cozy relationship with Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. He is also, as Jon Lovett put it on Pod Save America, a “right-wing zealotous billionaire nepo-baby,” like the Koch brothers, or Donald Trump, or the Roy children on HBO’s “Succession.” The son of the one-time biggest landlord in all of American, Crow is like a far more successful Donald Trump, if Trump had decided to exercise his interest in politics behind the scenes rather than under the spotlight.

He is also a world-class practitioner in the art of acquisition. As Pro Publica reported last week, Crow has not only treated his “close personal friend” Clarence Thomas to an conspicuous array of lavish perks, favors and gifts. Like Alan Ruck’s Connor Roy—whose nuptials formed the epicenter of Sunday’s blockbuster “Succession” episode—Crow is an avowed history nut. But Connor’s affection for “Napoleonica,” a recurring theme on the show, is relatively benign; Crow’s betrays a predilection for Nazi memorabilia. And not just the kind of pilfered SS dagger so many returning servicemen brought home from WWII. Crow’s Dallas mansion has table linens adorned with swastikas, a copy of Mein Kampf signed by Hitler, and one of der Führer’s original oil paintings. There’s even a “Garden of Evil” out back, featuring statues of the 20th century’s worst dictators, including Lenin, Stalin, and Mao. But strangely not Hitler, whose stuff is inside with the rest of Crow’s assemblage.

Crow, it seems, fancies himself the latest in a long line of very wealthy, very powerful, very obsessive collectors. Men like Constantine, Charlemagne, and Cosimo de Medici—whose bust has a prominent place in Crow’s own collection. What drives this compulsion? Carl Jung pointed to our hunter-gatherer instinct for survival, but it’s also an expression of identity, a means of fostering community and friendship, and in the case of the Uber-rich, an opportunity to show off.

The impulse to gather lovely and remarkable things has endured since the first syllable of recorded time, particularly among those with the status to accumulate en masse. “Tut Ankh Amon had collected fine ceramics while Pharaoh Amenhotep III was known for his love of blue enamels, and sanctuaries from Solomon’s Temple to the Akropolis as well as the courts of noblemen had always held famous treasures,” writes Philipp Blom in his delightful To Have and to Hold: An Intimate History Of Collectors from 2006. “Ancient Rome had seen a brief blossoming of a culture of collecting, mainly of Greek works of art, but with the empire that, too, vanished.”

Constantine, the last of the great Roman emperors, set the course for future collectors when the fruits of his pursuit of Christian relics began pouring into his namesake city, “that great repository of sacred bric-a-brac.” Several centuries later, Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor, accumulated not only relics, gems and books, but also the scholars and scribes to assemble those volumes, and then translate, transcribe, and codify them. In the 12th century, Saint Louis IX helped fund the legendary collection of the Abbot Suger, which included “a Greek vase with Bacchic scenes, a Sassanian bowl thought to be the cup of Solomon himself, a Roman stone bathtub that was placed behind the high altar, a unicorn’s horn, the teeth of an elephant, and a gryphon’s claw, as well as other curiosities.”

Though these items had unpleasantly heathen connotations, the sanctity of the other relics could not be doubted, for they included items once belonging to the Savior Himself: his swaddling clothes, parts of his crown of thorns, nails from the Holy Cross.”

Throughout the centuries, the nature of collecting has reflected the obsessions of the culture at large. The Middle Ages were a riot of relic-hunting, an often grisly expression of the religious hysteria that characterized Christendom at large. Blom notes that no fewer than 29 localities claimed one of the “holy nails” that pierced Jesus’ flesh on the cross (the implications of which—were they authentic—are too gruesome even for Mel Gibson to contemplate.) Eight cities boasted of the “holy foreskin,” and no less a critic than John Calvin noted that the sheer proliferation of breast milk from the Virgin would be inexplicable even if she’d been a professional wet nurse.

Despite bankrolling a litany of right-wing institutions and thinkers, many of whom are intimately involved with evangelical Christian politics, Harlan Crow’s collection doesn’t seem in any way religious. To find his historical role model, skip forward a few centuries, and squint until your standards drop: the likeliest inspiration is Cosimo de Medici, the Florentine banker whose largesse helped fund the Renaissance in the fifteenth century.

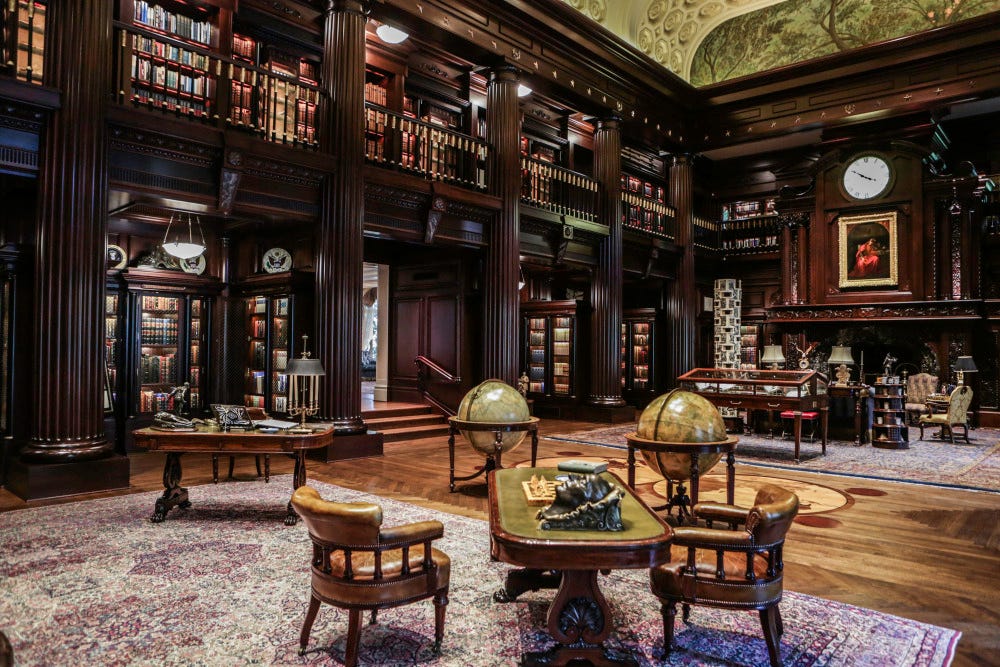

As a collector, Cosimo de Medici assembled one of the greatest libraries in history, and as patron he facilitated the efflorescence, preservation, and dissemination of more knowledge than anyone this side of Gutenberg. In a feature on Crow’s collection published in 2014, the Dallas Morning News ran a photo of a small garden alcove decorated with the busts of Cosimo and several of the artists and scholars he supported. Cosimo was no self-made man, but his passion and patronage would make the Medici family a true dynasty, and his blood would run through the veins of the kings and queens of France.

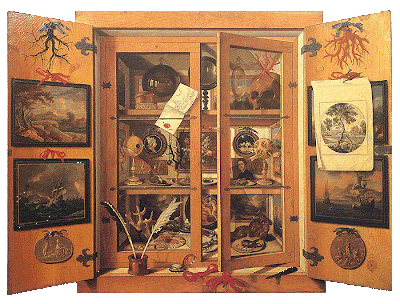

But Harlan Crow is more than just a few busts short of a full gallery. While it’s clear that Cosimo sought out and enabled beauty, Crow collects the artwork and ephemera of the worst people in human history. Much as he might aspire to place himself among history’s most august patrons of the arts, his defense is akin to a pope collecting Satan’s toenails. The legion of boot-licking sycophants who have leapt to Crow’s defense argue that he is commemorating the 20th century’s history makers, not celebrating them. This bespeaks a conspicuous lack of object permanence—one does not need to be in the presence of the relics of evil to abhor them—but it recalls a different, darker mode of historical collecting: the tradition of the cabinet of curiosities.

A fad that swept Europe towards the end of the 16th century, the cabinet of curiosities was what every self-respecting king, duke, bishop or other grandee just had to have, a sort-of mannerist take on the Renaissance studiolo. If the relic mania of the Middle Ages frequently confused the sacred and the profane, the cabinet of curiosities began with the macabre. And no cabinet was curiouser than that of Emperor Rudolph II von Hapsburg, whose “chamber of miracles” or Wunderkammer, was “the physical manifestation of this newly emerging mentality.” This legendary collection included pelicans, peacocks, and parrots, a turkey and a dodo, chameleons and crocodiles, blowfish and birds of paradise.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Rudolf’s fixation on the natural world was a prelude to an even darker chapter in the history of collecting—the indiscriminate, and utterly amoral, acquisition of whole people, enslaved and displayed like animals in a zoo. The most horrifying chapter in Blom’s book tells the story of Angelo Soliman, who was sold into slavery as a young boy in Africa. Purchased as a going-away present for the Austrian governor of Sicily, Soliman worked his way up from royal page to decorated soldier. By the time he died in 1796, he was a friend of the Emperor, a prominent member of Vienna’s masonic community, and spoke German, French and Italian, as well as some Czech, English and Latin. After his death, however, Soliman became the main attraction in the collection of Emperor Francis II.

Francis, like his ancestor Rudolph II, was a collector of natural curiosities, and when Angelo Soliman died in 1786, his skin was removed and stretched onto a wooden frame, so that his preserved remains could be arranged in a diorama in the Emperor’s collection. Ultimately, this noble African noteworthy was depicted “dressed with a feather belt around his loins and a feather crown on his head, both made from red, blue and white ostrich feathers in changing sequence. Arms and legs were decorated with a bead of white glass pearls, and a broad necklace braided delicately out of yellow-white porcelain snails (Cyprinid Monet) hung low down on to his chest.”

Owning the remains of human being is one thing, but how prestigious is owning a piece of a Supreme Court justice? Is it a greater or lesser status symbol than Hitler’s table linen, or the love letters of Napoleon and Josephine? Many a historical collection was the reward for rape and pillage—Napoleon’s comes to mind—and purport to be an enduring testament to grandeur. That type of collection is like a peacock’s tail, a macho display of potency for all to see. This pure dick-swing competition is what drove the greatest collecting frenzy in history, when Gilded Age robber barons like Carnegie, Morgan, Rockefeller, and Frick traded their ill-gotten New World fortunes for ill-gotten Old World collectibles.

This is the lineage from which Connor Roy and Harlan Crow hail: squirrelers-away of the grand and the grisly, spending the wealth of their fathers on trinkets both human and inanimate. It’s telling, and concerning, that alongside Hitleriana Harlan Crow has a habit of collecting people.

Throughout history, those who have felt the need to demonstrate their power have accumulated its outward trappings, from the lapis lazuli of the Pharaohs to the nightmare jumble sale of contemporary billionaires. “The greater a collection, the more precious its contents, the more it must be reminiscent of a mausoleum, left behind by a ruler determined not to be forgotten, not to have his memory squabbled over and his most immediate self disintegrate to dust,” writes Blom. “Here it is, material and incontestable, for all to see and touch; his memory, his ideal self, the expression of his wealth, his judgement, patronage, beliefs and substance.”

To collect is not to create; and perhaps the most powerful demonstration that one owns something is to destroy it. Everywhere clammy hands emerge from pockets packed with cash to grasp at the few things we hold as common goods. Everywhere soft mouths praise acquisition without limit, and fund privation that similarly has no end. You cannot fit a whole country in a cabinet of curiosities. But becoming a plundering ground for the rich and the recherché is a certain enough way of ushering in its end.

Fantastic!!

Another powerfully informative piece from you. Thank you!