Edited by David Swanson

The man lived a life isolated by his wealth.

He was proud of his blood, of the lineage he had bequeathed to his progeny, but this pride was compounded by a sense of profound insult. The land he claimed as his own had been stolen and soiled. He was beringed by a grand conspiracy, one that had ended the days of his ancestors’ rule, dripping with jewels and served by serfs.

He was displeased by the modern world—the one in which his sovereignty was in dispute, and in which people he considered his racial inferiors were putatively his equals—and so he set about finding ways to undo it. If you are rich, and you are wanton in your hatreds, those who share your odium will come to you.

The man began to espouse far-right politics, to embrace the worst of its tenets, and to utilize its special argot larded with conspiracy theory. He pandered to a group of fringe activists whose members gained increasing influence over his thoughts and actions. He did so in increasingly public ways, blanketing the town square with propaganda, and seeking out specific citizens for his attentions in ways that alienated and intimidated them. Nonetheless his chosen cadre remained loyal, even fanatically so.

His conversation became a constant game of allusions to a parallel universe of treacherous conspiracy. In speaking this way he inflamed ancient resentments, and stirred them up, profitably, among his exalted peers.

The man seemed to believe that because he wanted the world to change—and because he was of the right blood, and because he was rich—it would change. If, to some observers, it seemed like breaking the world … well, those observers were not worth considering. He wanted to take control, and so he would take control, and the collateral would float away like ashes, the detritus of history.

The Sword and the Sandwich is an exploration of serious extremism and serious sandwiches. To support this work and access all future content, please subscribe:

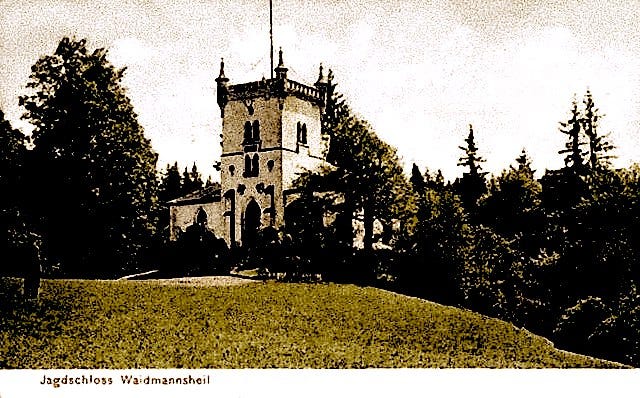

The man was a prince—Prince Heinrich XIII of Reuss, scion of a seven-hundred-year-old noble family that had once ruled a sliver of Thuringia in Eastern Germany. That is, until 1918, when a previous Prince Heinrich abdicated in the aftermath of the First World War. But the 21st century is no time for princes. Heinrich had to buy back Waidmannsheil, the great ancestral lodge in the village of Bad Lobenstein, from which he launched his plot to overthrow the German state. He believed his family ought still to be princes in practice rather than just title, and that the Jews and their allies had inflicted the great “stab in the back” that cost Germany the Great War in the first place.

Prince Heinrich cultivated allies among the erstwhile aristocracy of Switzerland and Austria, among the armed forces and the police, and, chiefly, among a faction of Germans who are a direct parallel to an American far-right movement. Like American “sovereign citizens”—a group notable for writing illegible court documents, refusal to pay taxes, and engaging in military standoffs with the U.S. government—Reichsbürger (“Reich Citizens”) do not recognize the legitimacy of the modern German state, calling it an unconstitutional corporate entity controlled by enemies of the people. The Reichsbürger form an influential bloc within the German right-wing, particularly in Thuringia, where the far-right AfD party is the largest political force in the state.

Heinrich XIII’s family disowned him after a public speech espousing antisemitic conspiracies; he found solace, in his isolation, in the company of the Reichsbürger and their compatriots, and in the planning of a coup. He saw himself as single-handedly restoring his house’s lost glory—though, as another Heinrich pointed out to the New York Times, he is only the seventeenth in line for the Reuss seat in any case. It is likely that his delusions gave him comfort; and beyond that, they provoked a conspiracy of powerful individuals, dozens of whom were arrested for attempting to install Prince Heinrich as head of a post-democratic, authoritarian German state, a Führer for the Fourth Reich.

It remains the temptation of those who have known wealth, comfort and power for their entire lives to feel nonetheless that their fondest ambitions have been subject to external spoliation. So they seek to violently conquer the errant world, which has failed to offer them due adulation. Even the petulance of princes is grand; it seeks out victims.

Where Heinrich went wrong—besides in every particular—was in attempting to rule as a prince, to reestablish a monarchy in a country that had long accustomed itself to living without it.

What he might have done—were he another wealthy and erratic individual whose desperate and delusive tendencies have become increasingly public; Elon Musk, say—was to purchase something important, and to wreck it. This simple act of destruction would have put his name on everyone’s lips not for a weekend, in which the masses felt unease and also contempt, but for the months or even years over which the process of ruination could sprawl, a beast with bad breath and worse taste.

He might have demonstrated his far-right tendencies through vulgar hints, the implied ellipses of conspiracy theory, and finally overt attacks on designated enemies of the far-right, symbolic effigies of a system of resentment which had overtaken whatever thin personality he ever possessed.

If you want to be an autocrat it is far easier to take over a company and terrorize its employees than a nation, the public at large being such a fickle thing. It is a smaller principality but far easier to control; to run it according to your whim comports with every law. Prince Heinrich was simply guilty of wanting to be a king; there are those who seek to colonize minds and planets with their wealth, and do so not clandestinely, but in public.

Nonetheless, the results of each—the one thwarted, the one ongoing—are similarly contemptible; similarly vulgar; similarly despotic and unnecessary.

The man who would be kaiser and the man who buys the praise of obedient scribes and the laughter of obsequious sycophants are possessed of the same hubris. In each case mewling individuals who long above all to surrender their wills to some paternal authority crawl in their wakes, licking at their footsteps. In each case what they seek is a mutilation of the world, to force each critic to become a lickspittle, to be enthroned in adoration of their good blood and all that they have accumulated. Each seeks rule, but only one attains it. This is not an age of princes, not an age of kings in name. Their heirs are only robber barons without titles, who use wealth as the weapon it always was.

I've always wondered if writers know in their bones when they've written a perfect sentence. This was a great article but this line stands out.... "If you are rich, and you are wanton in your hatreds, those who share your odium will come to you."