The Vanishing Act

On Harry Houdini, Arnold Rothstein, the Day of Holocaust Remembrance, and how hate steals the future

Author’s note: Please excuse the great length, late arrival, and wooly wandering of this column; I have given David some extremely well-deserved days off, and thus revealed his necessity to this endeavor.

Yesterday was a gray cold day with a carpet of wet dense cloud, like the soaked fur of some celestial dog, hanging low and smelling of rain – a good day to visit the sea, and graves. Manhattan having an abundance of proximate ocean there was enough time to stare into the fog-shrouded iron-colored expanse and think about losing oneself in it and then turn around and have lunch and head to Queens, where the dead of Manhattan seem to be buried in greatest numbers. We had meant to go to the graves of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, marked in no special way except their matching 1953 death dates, but West Babylon (what an appropriate destination for two souls in such profound exile!) – seemed too far a trek, so the Jackie Robinson Parkway spat us out into the sprawling cemetery complex that covers both sides of Cypress Hills Street.

The collection of cemeteries there are almost entirely Jewish, strata of generations in stone. You can tell a lot about a populace by how it situates its dead; even in death we Jews keep to ourselves, unwelcome in other neighborhoods, taking shelter in our own. But here where the outer boroughs accumulate the dead of all this sprawling city, the Jews have an outright necropolis, and among them are nestled great men. I felt as I did when visiting the great Jewish graveyard in Warsaw; though that place was partially destroyed, the earth rucked by mass graves, still the accumulation of stone on stone, the great men in their great tombs, told a story of centuries even the greatest malevolence could not entirely obliterate. Here in the late-emerging sun there was another such story, wrought in stone, in weeds and bees, in Hebrew lettering crisp or weathered according to the date of the death.

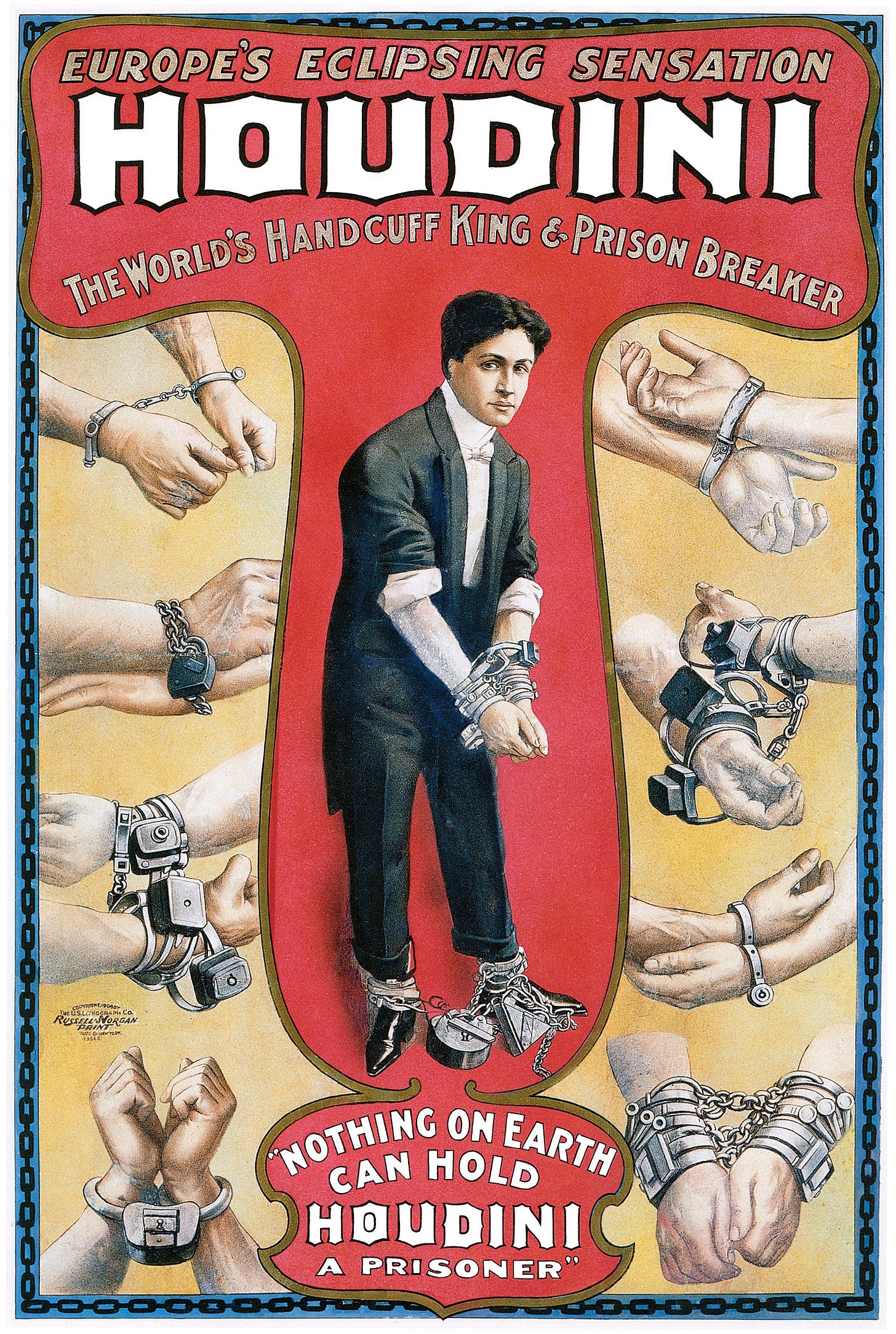

It was here that we found ourselves at the feet of the magisterial little family complex that marks the final resting place of the great Houdini. It’s just off the road, catercorner to the billboard for Machpelah Cemetery (the cave of Machpelah being the site where Abraham buried his wife Sarah in the Bible); on the billboard, in Russian for budget-conscious immigrant Jews, is an advertisement for “plots on sale.” And before us, a bust of the magician, carved aprés his last and greatest vanishing act: going into the earth too early, and staying too long, forever in fact.

There were dead Jews all around us – Rosenbaums and Roths and Baums and Steins in great profusion; in New York solitude is always an illusion, even in death someone is elbowing you – but Houdini, the showman, had carved out for himself a striking vantage. There was a black-clad couple seated beside the weeping angel on the curved stone bench that Houdini had commissioned for his parents’ graves, initially, and then in death topped with a detailed bust of himself. The strangers ran their fingers over the elaborate mosaic marking Houdini’s tenure as the president of the American Society of Magicians; a spring wind grabbed handfuls of the woman’s long dark hair; the magician and his wife lay at her feet, his parents and brothers, too, in a sward of weed thick with their enriching remains. Under the name “Houdini” is carved “Weiss” – the real name of the Hungarian-Jewish family of which he became posthumous paterfamilias. A man with a cane and a lip ring came after the couple and he left, in pride of place under Houdini’s foreshortened shoulders and solemn carved mouth, a combination lock prised open, just outside the reach of the angel’s palm. It’s traditional, when visiting a Jewish grave, not to leave flowers, but to leave a stone; together the stones make a sort of ragged cairn, a waymarker out of the world, a guide for the vanished.

There is much to be said about Houdini – how he died in such a stupid way, of his own hubris as well as appendicitis; how tender the inscriptions he presided over for his parents, a rabbi and a housewife respectively, are; how once he staged an escape from the belly of a beached whale in Boston; how shameless and how angry he was, and how small, a man determined to drown and escape drowning like a tiny Jewish resident of some Greek hell – but around the corner, quite literally, another dead Jew beckoned us.

It’s unnerving to visit a cemetery in spring, the insistence of life and the eternity of death are never quite so loudly proximate as when violets are bursting up against the stones, the birds are wittering and mating just out of sight in the sticky new leaves, &c – but I think to its credit Union Field Cemetery, chartered by Congregation Rodeph Sholom, may be unnerving in all seasons. It’s full of overgrowth, those graves selected to be tended marked by blue stickers reading “perpetual care,” and the rest left shaggy with vines and spackled with moss, so that an ill-kempt “Rosenbaum” is swallowed into “Rnbm,” like a neon sign half blinked-out.

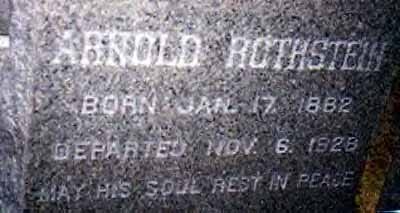

At Machpelah, Houdini has pride of place by the road and a steady stream of pilgrims even on a random April Monday. Our other visitation was to a less savory if no less theatrical Jewish fixture of Jazz Age New York, one who also died out of his season, though his line of work implied a low life expectancy – Arnold Rothstein, the great gangster-gambler, who trained a generation of famous malefactors to outwit Prohibition and the law. His grave is humbler, practically hidden; you need a map to get to it, and a small hike through a field of lesser dead. Still in his time he was no less great and no less known and no less able to execute one of the greatest tricks ever pulled on American soil.

Rothstein’s most crowning achievement was also a trick, if one achieved at less immediate peril to his own body; by all accounts, even if the charge never stuck, he fixed the outcome of the 1919 World Series, in the still-infamous “Black Sox” scandal. Less concretely, he brought a suavity and seriousness to the criminal underworld of New York that led it to see itself as an organization, rather than a discrete set of no-goodniks, and was one of the first to recognize the awesome profit presented by Prohibition. He saw himself, and was seen by others, as the velvet glove in which the iron fist of the street gangs coiled; he’s played that way, powdered and polysyllabic and grave, by Michael Stuhlbarg in an excellent turn on Boardwalk Empire. (This is no doubt a more fitting epitaph than the grotesque anti-Semitic caricature inspired by Rothstein, Meyer Wolfsheim, that appears in the patrician racist F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.)

But for all Rothstein’s elevated airs and grand company, he died a mug’s death – shot on 55th Street, most likely a blood payment for an outstanding $300,000 poker debt. The suspect, arrested and then acquitted, was one George “Hump” McManus, although Rothstein died without revealing his assailant’s name. To the untrained observer, a similar omerta covers his humble little grave, arranged in the center of a square of deceased Rothsteins, and covered with creeping ivy. One side – in English, and nearly obscured by the too-close gravestone of some guy named Levine – says only his birth and dead dates, with an additional “May His Soul Rest in Peace.”

But unlike Houdini, Rothstein’s parents outlived him. His father was a cotton-goods salesman of such legendary, prosperous probity New York governor Al Smith nicknamed him “Abe the Just.” And the frontispiece of the grave, one that faces the knowledgeable visitor, contains an original modern-Hebrew poem (you can’t mistake the Hebrew of the ‘20s – it’s a concatenation of Biblical and Mishnaic and Talmudic vocabulary squeezed into contemporary forms, a language just waking up to the possibility of living again), in defiant dedication to their criminal offspring. My clumsy translation omits the rhymes, but follows here:

Few were his years and many his deeds

His short life abounded with resourcefulness

He spread charity to all who were miserable and lowly

In his wealth and his strength dwelt the poor and downtrodden

And so his family embraced him after his death at 46 – not just in their proximity but in verse, a posthumous paean to the generosity of the ultimate prodigal son. I left a great hunk of a rock on his grave, to make up for its barrenness; the man was violent and indifferent to violence and died a violent death, but he, too, was loved, and too deserves a marker of distinction.

Juxtaposing him with Rothstein would no doubt have enraged the Great Houdini, a man prickly – and litigious! – with his soaring reputation. Still, the two are geographically entwined in death, and lived in parallel times, died parallel early deaths, left parallel imprints on the history of Judaism in America. Now they live in that Jewish forest of stone where beebalm slips out of the earth between the graves, and the mourners come and go, and the plots are on sale.

It’s been almost exactly a hundred years since Houdini’s death, ninety-five years since Rothstein’s, and while both experienced excruciating and lengthy demises, they were deaths all their own, predicated by the complex arcs of lives they chose. In Warsaw, where a comparable necropolis once stood; in Ljublanja, in Sofia, in Kyiv, in Moldova, in Lithuania, all across the continent Houdini’s parents and Rothstein’s grandparents fled, there are few graves left, and if there were a sufficiency, they would all show the same years of death. If by accident or mischance the boats carrying their ancestors hadn’t crossed; if they had stayed; Rothstein and Houdini might still have performed one last trick– they would have been part of the great vanishing we commemorate today through Yom Hashoah, the Day of Remembrance of the Holocaust. (My grandparents were Holocaust survivors, and survivors had to perform a great many tricks along the way – concealment and deception; the theft of potatoes from winter fields; learning to be deft and cunning or die; and ever after they carried with them the kind of trauma that washes over successive generations, enough to maul whole lives through epigenetics alone).

You have to come at a tragedy so big through all kinds of vantage points, big and small and curious, and it is a strange thing to write about the Holocaust starting at the grave of Harry Houdini. But looking at the graves of these two men, who each were great in their own distinctive ways – great tricksters, Anansis, who could make themselves or great quantities of money vanish at will – I am drawn to think, in this city of the dead, of the many, so very many, who vanished into the red tide of death with no chance to do the great good or the subtle craft they could have. Whose cunning was cut off, whose daring died, whose brilliance dimmed all at once when the gas-chamber door slammed shut on it? There is so much to be said about the grisly detail of such a tragedy, one that robbed a continent of so many millions of souls, deposited so many human beings into the furnace of hate and watched them burn.

The unsaid corollary, because one cannot measure a hypothetical, is what was stolen in their deaths: how many discoveries, how many great vaudeville acts, how many brilliant subversions of the law, how many strong wills making legendary destinies were cut off in that slaughter? This is what hate does in the end: collapses all individualities into one great undifferentiated threat, to be destroyed.

There are many who say it is disrespectful to take generalized lessons away from the Holocaust, that it imperils the unique evil of this thing to distill it into platitudes. I stand firmly against spooning kumbaya-style pablum from the death-pits of the last century. But when I look at these very different men, celebrated here in stone; and I think of all those who didn’t live to earn their celebrations, because the deeds they would have done dissolved in death-clotted air, instead – I think of this as a caution and a warning. I think of hate as a militancy against the future. I think of all the possibilities destroyed along with bodies. The ivy grows in the silence, the bees make sweet tracks through the golden air, the light bounces from the marble of the grave of Aharon ben Avraham, once known as Arnold Rothstein, from the bowed head of the weeping angel at the feet of Ehrich Weiss, who was once the Great Houdini. The last great vanishing act is one we all will do, in our straitjacket shrouds, dissolving into the earth, a miraculous transformation of flesh into dirt. All we can ask – all we can fight for – is that each one of us be given enough time to ripen into all we can be before that final curtain call, no matter where we come from, no matter who we pray to, no matter who we love, no matter our names.

Beautifully written. “Whose cunning was cut off, whose daring died, whose brilliance dimmed...”. What an important question! Hatred ends up robbing us all. Thank you for framing it in this way. ❤️

I thought this was beautiful, and the opposite of too long; I would have happily gone on reading for quite a while longer <3