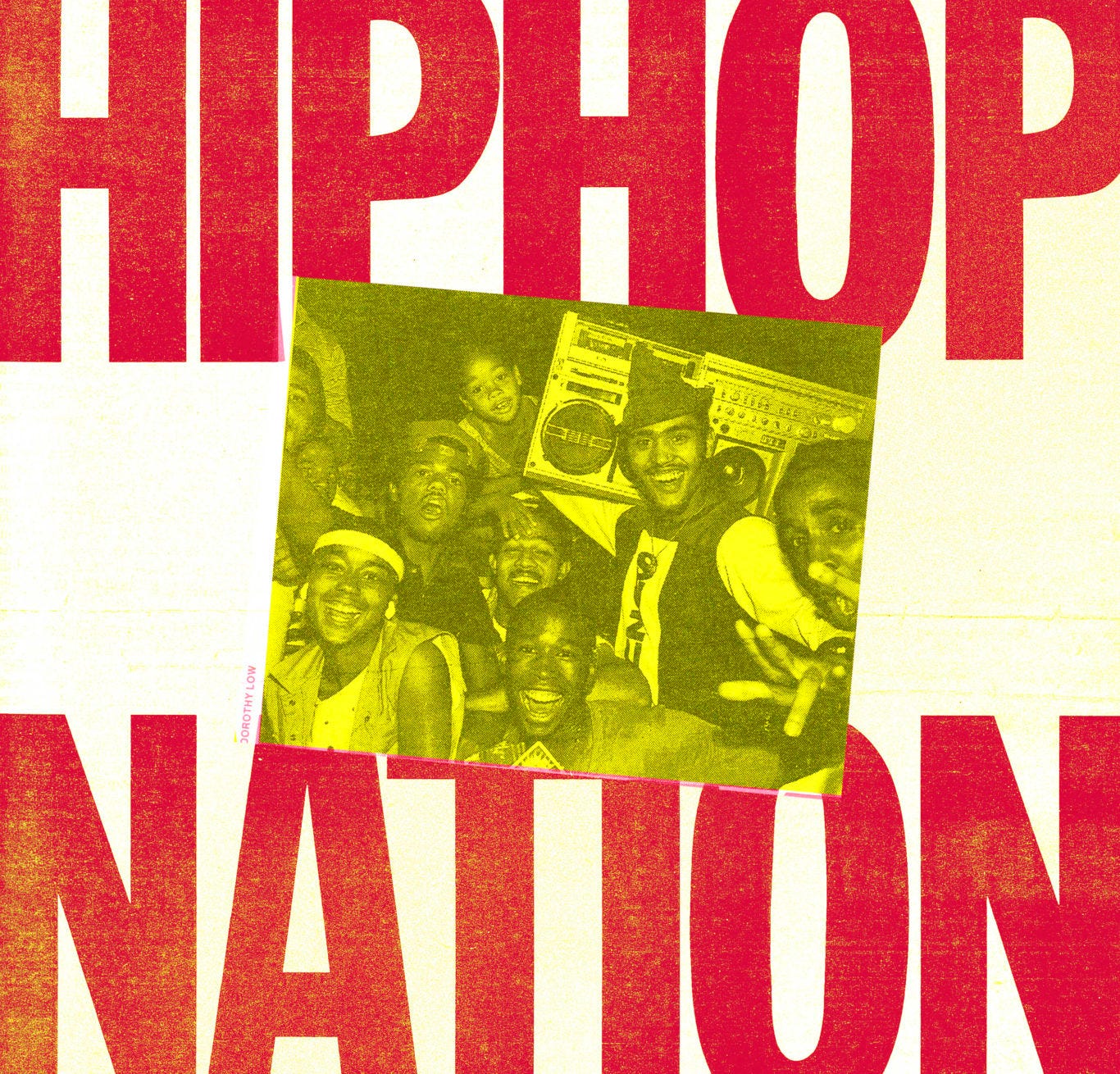

The Village Voice's Hip-Hop Nation

The history of rap, as told by Greg Tate, Nelson George, Harry Allen ... and all your favorite artists

Welcome back to Culture Club, a feature where David and I write about what we’ve been reading, watching, playing, and listening to, for paid subscribers. Please enjoy this free preview, and consider upgrading to support two struggling journalists at once! — Talia

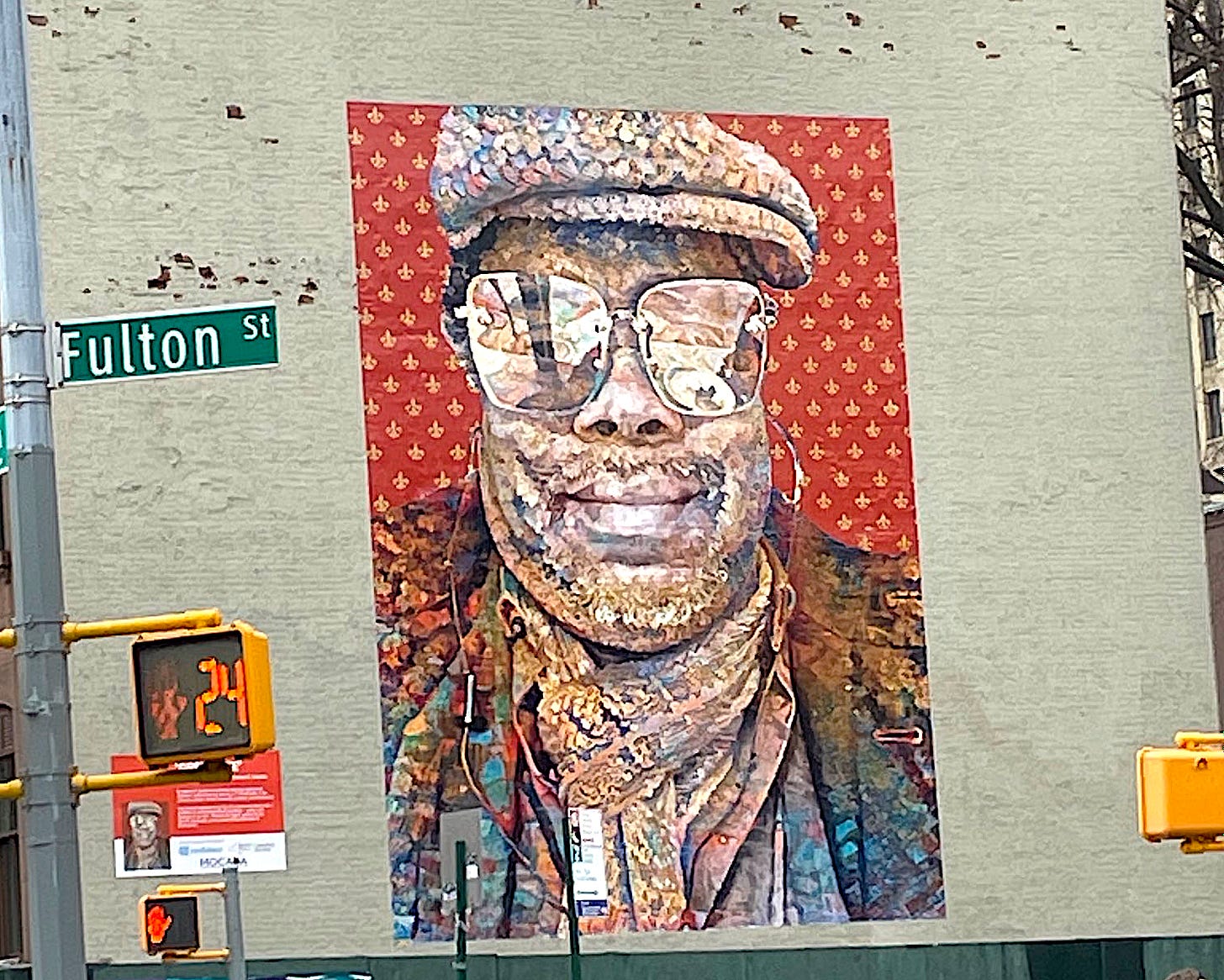

In case you hadn’t noticed, Hip-Hop Nation is having a moment. More specifically, it’s having a birthday. According to urban legend, the now ubiquitous art form was born fifty years ago, when, as Jon Caramanica writes in the New York Times, “DJ Kool Herc — in the rec room of the apartment building at 1520 Sedgwick Ave. in the Bronx — reportedly first mixed two copies of the same album into one seamless breakbeat.” That’s from the introduction to the Times’ ambitious, interactive “50 Rappers, 50 Stories” bonanza.

Predictably, this collection of interviews sent me down a rabbit hole — or back down a rabbit hole I was already familiar with. As an editor at the Village Voice, I spent hours poring over back issues from the eighties and nineties, reading along as the paper told the history of hip-hop in real time. What the Times’ project reminded me of most was “Hiphop Nation,” a 1988 Voice package featuring a murderers row of both artists and writers.

On August 11, at Yankee Stadium, Run-D.M.C., Lil Wayne, Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube, Ghostface Killah, Slick Rick, and more will be performing just a mile or two from the spot where Kool Herc first rocked the turntables exactly fifty years before. Designating this particular date as the hip-hop’s big bang moment seems fairly arbitrary — shades of Abner Doubleday — but I’m all for a birthday. After all, the history of hip-hop is fascinating and worth celebrating, which I think you’ll find in tonight’s collection of articles from the golden age of the Voice, and the golden age of hip-hop.

In addition to the expected profiles DJs and MCs, I’ve included early coverage of breakdancing and graffiti — featuring Jean Michel Basquiat and Fab Five Freddie, though they didn’t use those names at the time. I should note that these are pretty bare-bones posts, but nudge nudge you can read them with art and scans of the original pages by running the links through the Wayback Machine. It’s a good supplement to all the other ways you can commemorate this momentous occasion — and if this post leads to anyone discovering Greg Tate for the first time, it will have been worth it. As he wrote in his introductory essay from 1988:

“Latter-day prophets predicting hiphop’s imminent demise have already become extinct. Afrika Bambaataa sez rap will be around as long as people keep talking. You think we’re gonna let ’em shut us up now? Sheee.”

Are you ready for this?

SAMO© Graffiti: BOOSH-WAH or CIA?

by Philip Faflick

December 11, 1978

Is no surface sacred? They do stay clear of most private property, but government property and corporations are fair game, especially subways, elevators, and public toilets. What about the millions of taxpayers’ dollars spent each year cleaning up? Jean [-Michel Basquiat] has a ready reply: “That’s a drop in the bucket compared to how people are getting shafted in big ways.”

Jean is more troubled by his questions. Is it a cop-out to give SAMO©’s story to the papers? Is it anti-cool to take credit for street art? And what of their ambition to some day work in art-related jobs, isn’t that BOOSH-WAH?

And it should be reported that in the process of helping me with this story Jean and Al came under some rather pointed criticism from their friends, who worried that a taste of fame would go to their heads.

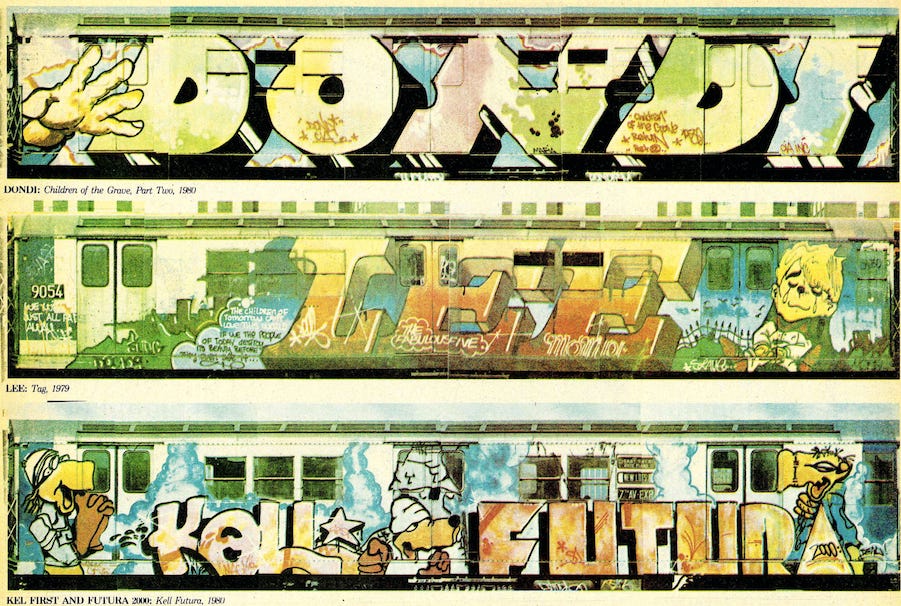

In Praise of Graffiti: The Fire Down Below

by Richard Goldstein

December 24, 1980

Fred and Lee are stalwarts of the Fabulous Five, a group that writes on the number five line of the Lexington Avenue IRT. When I caught up with Fred, this 24-year-old veteran expressionist was en route to Milan, for a show at the Paolo Seno gallery. This is his second Italian exhibition; the first was warmly received by Unita, the Communist Party paper, which suggested that the Fabulous Five be hired to paint the Victor Emmanuel monument (built by Mussolini and contemptuously known as “the wedding cake”).

“My art is like an artifact,” Fred says. “Like, the paintings I do, I want people to look at them as an art based on graffiti.” He has started reading Artforum. He has developed a fondness for Dada. He has cut a rap record. “With a little time and paint,” Fred says, “anything is possible.”

Are You Ready For Rapping?

By Barry Michael Cooper

January 21, 1981

Are you ready for this? Well I just can’t miss, a with a beat like this. The beat — the beatbeat — the fonky beat is the key to rapping. And that’s what turns a lot of white and black listeners off. The beat is a product of the street and all of its raw, primal, and instinctive energy. These transcontinental urban griots echo the despair, pain, and anger of the South Bronx and Harlem (the world’s two major rap centers), which a lot of the cool-jerk white liberals and b.s. black bourgeoisie don’t want to hear. Rapping reminds them that everything is not cool and correct on the home front, like punk rock in England and reggae in the Caribbean. In fact, the “toasting” records of the West Indies are reminiscent of American rap.

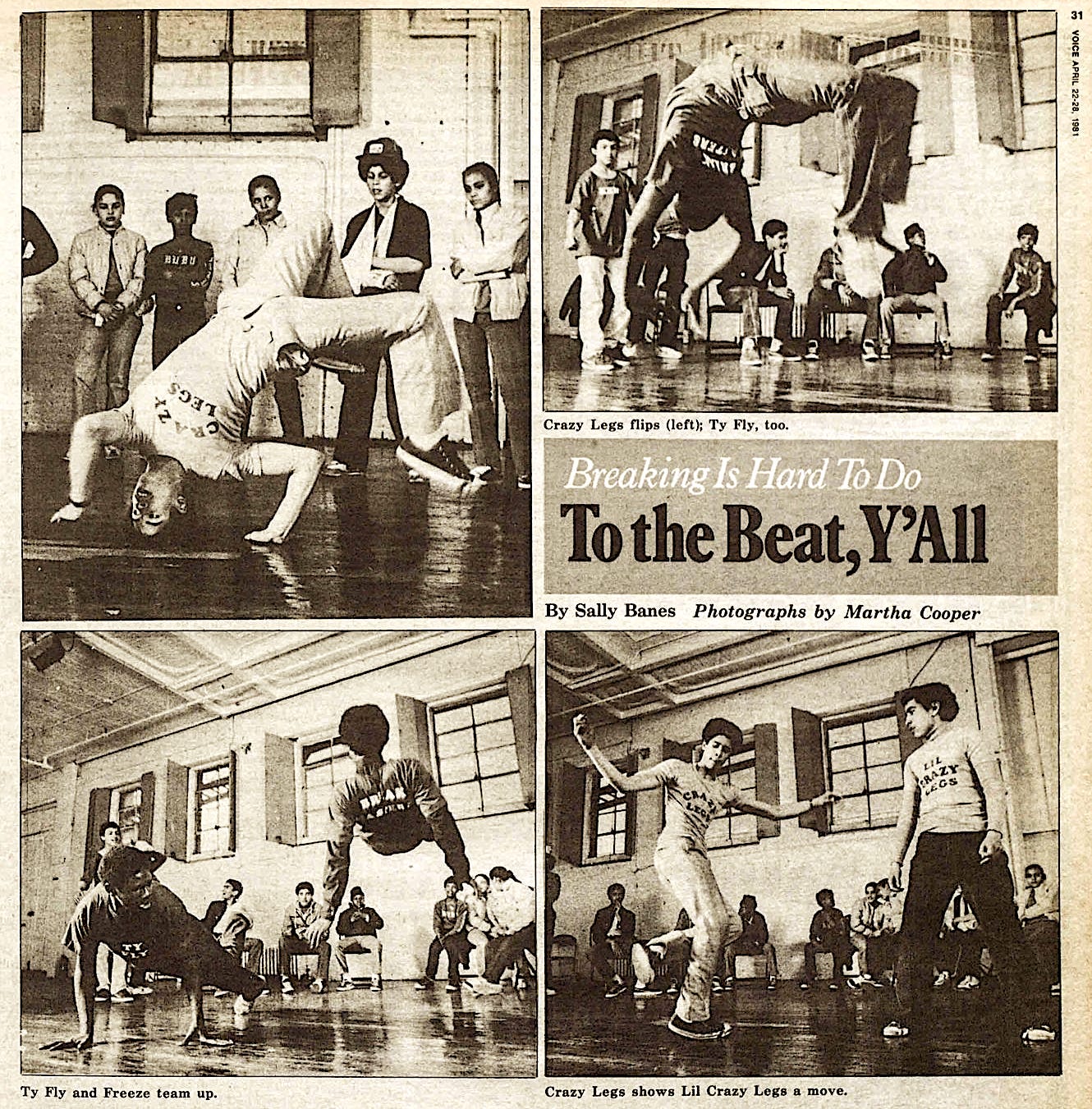

Physical Graffiti: Breaking is Hard to Do

by Sally Banes

April 22, 1981

Like other forms of ghetto street culture — graffiti, verbal dueling, rapping — breaking is a public arena for the flamboyant triumph of virility, wit, and skill. In short, of style. Breaking is a way of using your body to inscribe your identity on streets and trains, in parks and high school gyms. It is a physical version of two favorite modes of street rhetoric, the taunt and the boast. It is a celebration of the flexibility and budding sexuality of the gangly male adolescent body. It is a subjunctive expression of bodily states, testing things that might be or are not, contrasting masculine vitality with its range of opposites: women, babies, animals; illness and death. It is a way of claiming territory and status, for yourself and for your group, your crew. But most of all, breaking is a competitive display of physical and imaginative virtuosity, a codified dance form cum warfare that cracks open to flaunt personal inventiveness.

Run-D.M.C.: They’re Gonna Smash Their Brains In

by Greg Tate

April 9, 1985

Consider for a moment that if hiphop does nothing else, it at least draws a few black youth out of the firing line; forces folk to see some young black men as something other than thugs, as possibly possessing a little intelligence, even if only for the duration of an MTV video. Let’s call this the liberal position. For a less tolerant view, cut to the Run-D.M.C. show I walked out on at the Beacon last Saturday (the late show, not the 7 p.m. which went smoothly) not because I walked in on the sight of several hundred black teenagers standing on their seats screaming “do that shit, do that shit” in a game of call and response with a deejay, but because, when people started running out of the orchestra doors yelling about a rumble in the balcony my partner-in-crime and I decided that given the vibes, it was time for our bourgeois black bohemian behinds to get the fuck out of Dodge.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sword and the Sandwich to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.