It was spring in Colorado when the National Guard killed the strikers: April, 1914. Workers at John D. Rockefeller’s big interest in the state, the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, had been on strike since the previous September, and had long since begun to live in tent cities around the mines. The company, meanwhile, had long since hired men to try to kill just enough miners to get the rest back to work, sending out, in October, an armor-plated car the miners dubbed the “Death Special” to shoot up a camp in Forbes, Colorado. The provocation for all this was the miners pursuit of “improved conditions, better wages, and union recognition” through the United Mine Workers union. The eight thousand strikers were in many cases demanding protections already required by Colorado law: an eight-hour workday, the right to live outside the company-owned town, a ten-cent raise. The laws had never been enforced against Rockefeller’s interests. Few things were.

By November 1913, the Rockefeller family directly intervened with the state, convincing governor Elias Ammons to send in the Colorado National Guard, a ragtag collection of veterans whose wages came straight from the enormous Rockefeller fortune. They functioned as a militia, harrying the mining camps. Still, the strikers held out through the winter in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo mountains.

In April, John D. Rockefeller himself—the great lipless teetotaler, with his aquiline nose and beady eyes—appeared before the Congressional Committee on Mines and Mining, addressing an inquiry into the strike. The investigating subcommittee’s chairman, congressman Martin Foster of Illinois, quickly ascertained that the Colorado state militia was on Rockefeller’s payroll; that Rockefeller himself had not visited Colorado in ten years; that Rockefeller was aware of the armored cars with machine guns mounted on them manufactured by his company and used in harrying the miners; that Rockefeller knew full well through his agents about the ongoing killings taking place in the iron-rich hills.

The Congressional testimony is remarkable and worth reading in full, but it is this exchange that has emerged with its own especial infamy:

Mr. Rockefeller: There is just one thing, Mr. Chairman, so far as I understand it, which can be done, as things are at present, to settle this strike, and that is to unionize the camps; and our interest in labor is so profound and we believe so sincerely that that interest demands that the camps shall be open [non-union] camps, that we expect to stand by the [Colorado Fuel and Iron Company] officers at any cost. It is not an accident that this is our position—

The Chairman: And you will do that if it costs all your property and kills all your employees?

Mr. Rockefeller: It is a great principle.

The Chairman: And you would do that rather than recognize the right of men to collective bargaining? Is that what I understand?

Mr. Rockefeller: No, sir. Rather than allow outside people to come in and interfere with employees who are thoroughly satisfied with their labor conditions—it was upon a similar principle that the War of the Revolution was carried on. It is a great national issue of the most vital kind.

It wasn’t any kind of revolution that unfolded 14 days later on April 20: just another morning in the rambling tent colonies. Then the National Guard breached the camp and the Ludlow Massacre began. Both sides were armed but the Guard was armed better, with machine guns, and they shot labor leader Louis Tikas three times in the back under a flag of truce. Just as would inevitably ensue soon after in trenches of Europe, the trapped strikers burrowing into any slough or depression they could find to avoid the hail of bullets; women dug pits beneath the tents to shelter in. At dusk the Guardsmen set the tents aflame with torches. The next morning a telephone lineman going through the ruined tents lifted an iron cot covering a pit and found thirteen charred bodies: eleven children and two women whose last breaths were smoke, and whose names are unrecorded.

The Ludlow union was never recognized. The strike was crushed by federal troops, and not a single guardsman was prosecuted, nor any of the private thugs hired by Rockefeller. Not a hair was mussed on the titan’s head. His name adorns halls at Cornell and Bryn Mawr and Vassar; a biomedical research institute in New York City; avenues in Paris and Munich. Money has always been better than bleach at washing out bloodstains, a housekeeping tip aspiring philanthropists have abided by for a century and more.

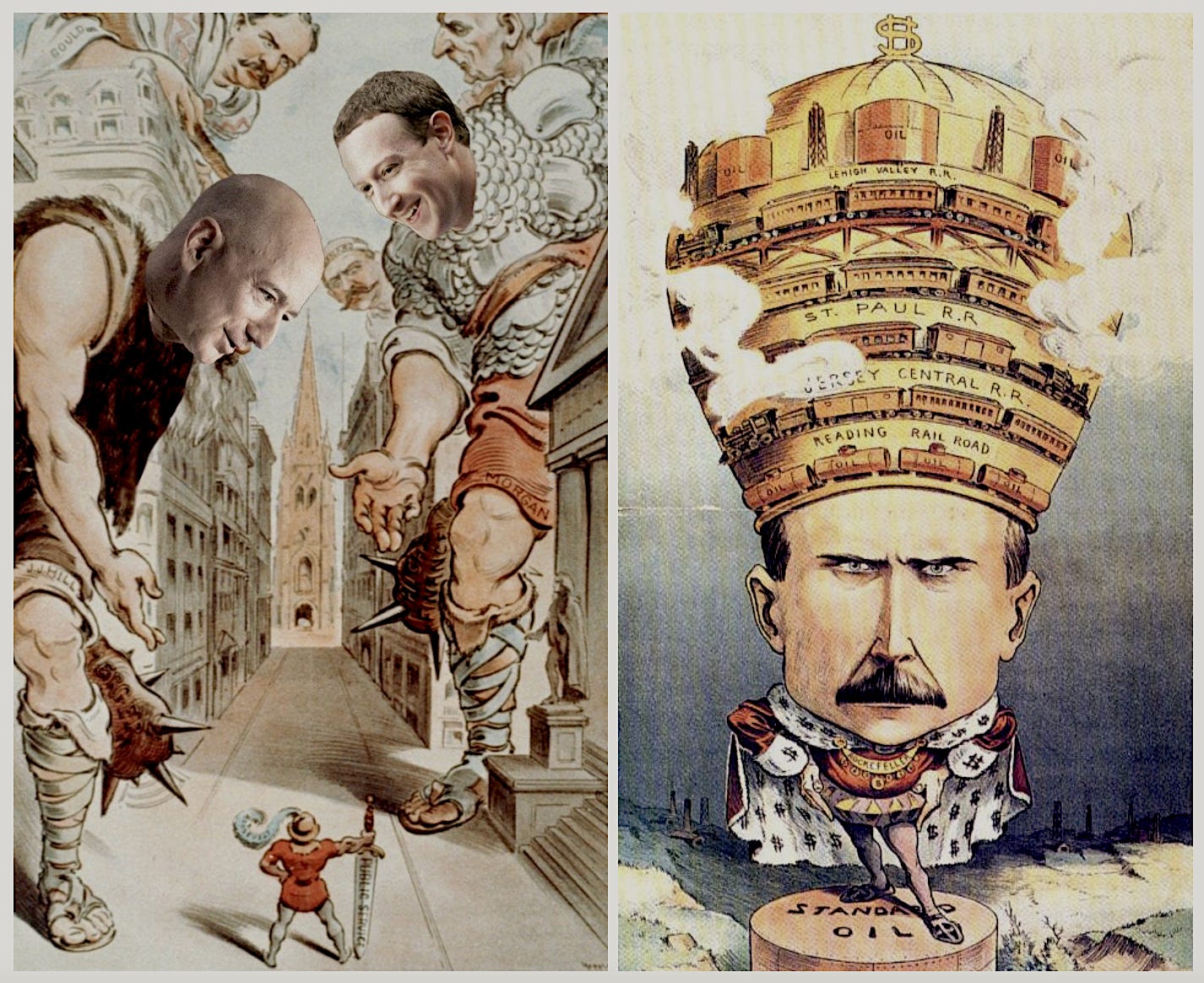

Less than a century after Rockefeller’s death, America’s titans of industry are no longer even bothered to build libraries or dormitories or research institutes of especial note. The robber barons of the tech sector buy senators and journalists, certainly, but rarely feel the need to erect any monument to the public good; if they create anything big and showy, like a spaceship or a tunnel, they have already been subsidized for it handsomely, by states and municipalities that pant after them like schnauzers, the rag-eared dogs of capitalism’s decline. The robber barons of 2023 don’t kill like Rockefeller either, not in this country at least; what happens in factories and cobalt mines overseas doesn’t make A1 in the Times. They kill, though, steadily, they have been killing for years now, the slow leeching death by a thousand cuts.

They killed the newspapers and the cabbies, killed the last vestiges of financial regulation. They “incubate” ideas that always seem to amount to giving people who look like them large sums of money to squeeze profits out of their customers, insinuating themselves into every aspect of daily life where money is concerned. The operating verbs are: tap, swipe, like, subscribe, die. There’s probably a VC funded app where they coordinate how to fuck us over, and it’s probably called Robbr. American life expectancy keeps getting shorter as the blockchain grows.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

The whole argument these tech-bro vultures make is that they deserve the ennoblement bestowed in their pet bought press and from their simpering fans because of the risk they take on, in innovating new ways to make it more expensive and confusing to buy clothes and drive and pay rent and get groceries. Such terrible risk! Hundreds of millions might become tens of millions at a moment’s notice. So it’s worthwhile, laudable, wondrous to watch hair-plugged, hoodie-wearing self-proclaimed gurus play with unimaginable amounts of money, creating such vital innovations as cartoons of apes on the computer you can buy for a lot of money, or buying a social media site to make it worse; driving up profit margins in healthcare, building a Lego-themed metaverse for children rife with microtransactions, and so on. All of it is parasitical and will soon be inescapable. They’ve all read Ayn Rand and that one quote from Teddy Roosevelt about being the man in the arena, and they all consider themselves Randian arena-men whose critics are Lilliputian cowards who would never take on such enormous and terrible risk.

Except they didn’t. When Silicon Valley Bank and a few analogous institutions collapsed over the weekend, in a matter of days the federal government—so often lumbering and ursine in its movements—took control of $150 billion in assets and backed them from the Treasury. Is it a bailout or a rescue? Who gives a shit. The risk is nullified, the banks are safe, the robber barons protected as ever they were by governmental friendlies. Putative Randians guzzling federal subsidies isn’t even worth much comment; flagrant exercise of hypocrisy is, as ever, really an exercise of power.

What really galls, though, is how much they get given when they fuck up, and how much everyone else gets punished. In most cities—thanks in no small part to this horrid cohort—if you lose your home you can be rounded up into camps; they’ll call you a scourge and a disease on the nightly news; policemen steal your belongings and wreck them. If you lose ten billion dollars because you bet on imaginary apes you just get it back with a governmental guarantee.

There’s something honest about bullets and pits and mercenaries. About Rockefeller going before Congress and saying that he was perfectly willing to kill every last one of his employees dead before letting them join a union. (Andrew Carnegie, a fellow robber baron, by contrast, fled the country to a retreat in Scotland during his own labor massacre, leaving the violence to his brutal lieutenant Henry Clay Frick; a dozen people died during the protracted Pinkerton-striker gun battle at Homestead Mill. And it was the National Guard of Pennsylvania, not Colorado, that ultimately broke the strike and ushered in scab labor. Still, after the strike broke, the titan cabled Frick: “First happy morning since July.”)

I’m not by any means saying you gotta hand it to the robber barons of the Gilded Age. I’m just saying the new Gilded Age looks like shit in a different way. Tech bros are astounded at how little they are liked outside their California bubble, they are genuinely hurt that the unwashed poors dare to contemn them, they feel both deserving of and in need of constant streams of public adulation. They do not feel the need to build a thousand libraries and launder their blood money out with blood marble; they just expect that, having been told “yes” all their working lives, “yes” is the only word that could fall from the wet hungry mouths of the unwashed masses. The whole thing is as tawdry as it is hellish. At least when a Carnegie goon killed your friend it was a bullet, not despair, that did the deed, and you weren’t expected to keep walking.

It is impossible to state how disgusting it is to watch the smooth rapidity and seeming inevitability of the rescue of billionaires by the federal government. The precariat, meanwhile, is expected to hang on by bloody fingernails and is then blamed for falling. Thirty-two states are cutting food stamps this month in what experts are calling a “hunger cliff” for families. All the birds are dying of avian flu and eggs cost fifty percent more and a gallon of milk is about five bucks on national average. After tech companies pushed through legislation in California to make app-based workers independent contractors, drivers for Uber and Lyft were left to survive on about $6 an hour, even less than the stagnant federal minimum. Student loan debt relief, even in the means-tested and modest form reluctantly advanced by the Biden administration, is currently blocked from accepting new applicants by court injunction; even for those few who managed to apply, there’s a strong possibility of crippling payments being resumed this summer.

The government moves slowly when you’re not a billionaire, and it demands you earn your dollars with pain. There is always so much to assess. There are humiliating and byzantine trials, Augean stables’ worth of shit to clear, before you can access benefits. Around one-fifth of the nation’s adults have rotting teeth because they can’t afford to see a dentist.

I suppose this is all a very long way of saying that this is a sadistic place to live unless you’re rich. It’s telling that “incubation” is the tech-bro term of art for coming up with ways to squeeze pennies out of proles, and it makes sense: they bathe in artificial warmth, the world is a fat egg with a ripe yolk to suck, and they cluck congratulations to themselves as they sit on their well-funded asses. A late chill spring is coming, one hundred and ten years after the Ludlow massacre. There’s nothing like the plucked feathers of fat geese to keep out the cold.

Beautifully written from start to finish. And tragic.

As someone who lives close to Silicon Valley and works in IT -- and absolutely detests the "disruptive" startup culture and VCs -- it is so good to see my own thoughts so beautifully and eloquently put into words. Thank you!