War Music: A Short History of the Ukrainian Language

Putin's "humanitarian special operation” is just the latest chapter in a long struggle for survival

Edited by David Swanson

How do you contextualize a war? The realities of it are beyond comprehension, of course: cities bombarded, the number of dead in the tens of thousands and the displaced in the millions, the destruction of cities in their entirety, the bodies of soldiers and of women and of children sprawled out in the snow, their limbs whorled out, bloody props for newscasts. These images and experiences are both impossible to translate and universal: the weather may change, but rubble and corpses look the same everywhere, and screams are their own primal language.

The Russian word for “mass grave” is bratskaya mogila—literally translated, it means “brothers’ grave.” On February 21, Putin’s late-night address just three days before war was launched described Ukraine as a brother nation to Russia, “an inalienable part of our own history… bound by blood, by family ties.” He would ultimately be proven right, that Russians and Ukrainians are indeed bound by blood, but not quite in the way he meant: killing each other and dying in the streets of ruined cities. A brothers’ grave, a brothers’ war: Putin, in advance, tried to cast his invasion as a kind of internecine struggle, justifying conquest and annihilation by pretending there was no true polity to be invaded and no real border to be crossed. The speech was almost entirely focused on history—false and totalitarian history, the past as propaganda—and it meandered from the 17th-century Russian empire to 1920’s Soviet nationalities policy and eventually to the present.

Squarely in Putin’s field of attack was the Ukrainian language; he objected to the idea of Ukrainian as the national language of its country of origin, and claimed to be fighting for “language diversity” in Ukraine. Less than a month later, the idea that a war this barbaric was launched for “language diversity” feels even more preposterous than it did in the first place. But of course the lie that Russian speakers have been subject to genocide, that Ukrainian is not a “real” language, that its speakers are fundamentally illegitimate and suspect, is as much a part of this “humanitarian special operation” as any other pretext.

Much of the war coverage written by Western journalists, particularly those writing from abroad, tends to focus on the geopolitical stakes of the war—Russia’s new alignment with China, the sudden unity of NATO, the hovering presence of nuclear weapons, the effects on the global food supply of Ukraine’s abortive spring planting, etc. And all of this matters, but to my mind the specifics of the region matter too. They are complex, and labyrinthine. Where to begin? There’s a good joke that Seva Gunitsky, a Russia-focused professor at the University of Toronto, posted to Twitter a few weeks before the war broke out that sums up the dilemma nicely:

I thought I would start with language, since the Ukrainian language is in the crosshairs of this dictator, and there is reason to believe that, if his conquest, God forbid, takes hold, its musical syllables will be barred from the public sphere. Already, in the occupied city of Kherson, Ukrainian-language TV has been replaced by Russian television broadcasts, subsuming residents in a bubble of false information—banning any truth from the airwaves, and encouraging the populace to become alienated from their own tongues. Meanwhile, Volodymyr Zelensky, a native Russian speaker from the largely Russian-speaking industrial city of Kryvyi Rih in central Ukraine, has been giving his serial addresses in his second language of Ukrainian, broadening his “o’s,” hitting the flat and unique “i” sound alien to Russian ears when he says “we are defending our country.” Only when he is encouraging Russian soldiers to defect, or Russian citizens to protest the war, does he change his language of address—but he can, as can millions of Ukrainian citizens, speak both languages nearly interchangeably. The hangover of Soviet Russification, and the accident of geography, means that many Eastern and Central Ukrainians speak Russian; life in the capital, Kyiv, is profoundly bilingual.

This doesn’t mean that Russian and Ukrainian are the same language—or even particularly close. They do not even have identical alphabets: Ukrainian has four distinct letters, Ґґ, Єє, Іі and Її, and dispenses with three letters used in Russian. Neither are they mutually intelligible: a sentence in Ukrainian to my Russian-speaking roommate is almost entirely foreign, both in pronunciation and in vocabulary. Even basic words like “father” differ: “bat’ko” in Ukrainian, “otets” in Russian. Ukrainian bears distinct similarities to Western Slavic languages like Polish in its vocabulary, and its grammar is even more complicated than Russian’s (which is, as someone who has attempted to learn both, really saying something).

But it’s the rhythm of the two languages, their sound, that differs most profoundly: Ukrainians love to say that they have the most musical language in the world, second perhaps only to Italian. (I have never heard an Italian say that their language is as musical as Ukrainian, but perhaps I simply haven’t met the right Italian.) Where Russian feels closed, consonant-heavy, Ukrainian is melodic; speaking sentences aloud in each, I feel my mouth open more when I speak Ukrainian, a lilting cant upward in my speech, so that while I say “miy bat’ko zaraz u viyniy”—my father is at war now—in Ukrainian, I say “moy otyets seychas na voyne” in Russian. Only two words are cognates, the vowels transposed. Both languages are beautiful, but their music moves in separate keys. And of course—only one is the language of an empire.

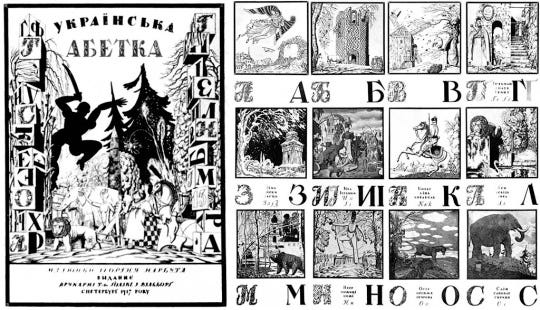

The history of Ukraine is rather dizzying in any case, dating back as far as it does—Ukraine was chronicled by Herodotus; Ovid lamented the barbarity of its Scythians from his exile on the Black Sea—and playing host, as it has, to such a broad array of occupiers, from the Golden Horde of Genghis Khan to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and on and on across the steppes and centuries. (The best book I have read on the subject is The Gates of Europe, by the historian Serhii Plokhy.) Its language has, accordingly, picked up pieces of each of these influences, including the Yiddish of the Jews that have made Ukraine their home for centuries. Philologists have traced proto-Ukrainian—that is, a language in the area of contemporary Ukraine distinct from other Slavic dialects—to the sixth century A.D., and literature in Ukrainian from the mid-eleventh century. The modern history of Ukrainian, from the 1700s onward, however, is the chronicle of a struggle for recognition and against imperial censorship, mirroring the struggle of the country to emerge as a separate polity.

This week, I spoke to the Odessa-born poet Ilya Kaminsky, who told me about the complicated history of his homeland: “1918, the year my mother’s mother was born, her family crossed the border nearly a half-dozen times, without ever leaving their Odessa apartment. Month after month, the region was invaded by various foreign regiments: Greeks, French, Poles, Germans, Romanians, Brits, Austro-Hungarians. Of course, the border had been a struggle for them as the city of Odessa was so divided between governments—French, Greek, Ukrainian, Romanian—that the family needed a travel permit just to see their cousins in the next street. Yes, crossing the border had always been a struggle—but that year, 1918, the border crossed through them.”

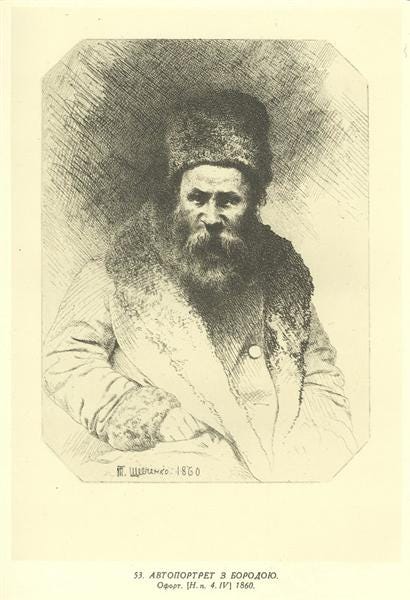

In the centuries before, Ukrainian books had been censored out of existence by Russia’s tsars, hindering the language’s literary development out of an imperial fear of any distinct national identity arising in the region. It was viewed as the vernacular of peasants, relegated to comic sketches of rural life, until the Romantic literary movement moved poets and writers to enshrine popular folklore in their works in the early 1800s. The first great Ukrainian poet, Taras Shevchenko (known as “Kobzar”—the bard), was born a serf in 1814; he began to paint in secret, and eventually used the proceeds from a sale of one of his paintings to buy his own freedom. He went on to synthesize, in his works, a new literary Ukrainian language; after Tsar Nicholas I read a poem of Shevchenko’s that criticized the imperial family, however, he was exiled, first to the Ural Mountains, and then to a penal colony in what is now Kazakhstan. Such was the price of writing in Ukrainian—for him and many others.

The brutality of Ukraine’s history in the twentieth century is breathtaking—for further details, I recommend Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, which goes into the depravities of both leaders against a captive populace in haunting detail. Stalin starved Ukrainian speakers by the millions; of those who survived, hundreds of thousands more were shot or deported. Along with its people, the language was repressed, its poets imprisoned or killed, in waves of official crackdowns that roiled down the length of the twentieth century; once again Ukrainian books were censored out of existence. People died for writing in Ukrainian and died for speaking it. Ukrainian intellectuals were sent to labor camps, to penal colonies, to isolated graves. Then as now, to speak Ukrainian in and of itself was viewed as alien, suspect, a threat to imperial strength—and then as now, there were defiant Ukrainian speakers who went on speaking and writing in it nonetheless, at great cost.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

If Russia and Ukraine are brothers, they most resemble Cain and Abel, with the current atrocities born of a fratricidal impulse. (Fittingly, the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture recently released a series of graphics bearing the message: “We are not the ‘younger brother!’”) But both countries have songs for the war dead, having seen so many die in war, and the songs are beautiful, though they differ in the tone of their keening. Two of the most famous both feature birds: Plyve Kacha, a Ukrainian ballad that has featured in collective lament for centuries, focuses on a gander that swims peacefully on the Tysyna River while a soldier dies far from home—“I do not even know where I die.” Chorniy Voron, a Russian folk song of indeterminate age, features a dying soldier staring at the black raven circling above him, eventually accepting that he will become its prey: “Tell my darling mother/I died for the Fatherland.” They are both sad songs, even maudlin; they each feature young men thinking of their mothers as they die; and in both countries now there are indeed newly bereaved mothers, and newly dead young men. But these lamentations hover on different lips; they are born of different traditions, and it is precisely because of this—that one people dare to speak their own language, and demand a future for themselves beyond that of an imperial possession—that these corpses are cropping up in the March snow, where there should be crocuses.

The bandura, a sixty-string Ukrainian lute, was traditionally played by kobzary, itinerant bards who were often blind; in 1933, under the guise of a trip to an ethnographic conference, Stalin’s NKVD gathered and killed hundreds of these singers outside of Kharkiv and dissolved their bodies in quicklime, because they sang in Ukrainian, about Ukraine. There are bandura players again now in Ukraine, new bards for a new era, if not a kinder one.

Here is Inna Ishchenko, a young folk singer, singing “Plyve Kacha” on the bandura.

And here’s one of countless renditions of “Cherniy Voron”:

And let the birds say it and let the singers say it, in Russian and Ukrainian and every language there is—no more people dying in the snow, as lonely as everyone is in death, no to war, no to bullets, no to bombs. The two languages differ but one word is exactly the same in both: мир—peace.

thank you for your work. i'm a kiev born soviet refugee (i guess its one of the other USSRs) who's been watching with horror as a place i left more than 40 years ago is turned into a killing field. its been particularly hard to reconcile this positive attention on ukraine and culture with its history of pogroms, jewish genocide, nazi collaboration, and recent right wing nationalist prominence. i don't say this to defend russia's attack in the least but to note the discombobulation i experience in thinking about what's happening there. in light of your work in tracking these right wing movements i think we'd all really benefit from your diving into this topic.

So powerful and beautiful. I always learn a new perspective when I read your work. Thanks. Peace!