What is "The Great American Novel"?

This is a newsletter with major Moby Dick Energy

Welcome back to Culture Club, a feature where David and I write about what we’ve been reading, watching, playing, and listening to, for paid subscribers. Please enjoy this free preview, and consider upgrading to support two struggling journalists at once! — Talia

Inspired by last Sunday’s newsletter on Herman Melville’s time on Maui, I’ve spent this week dipping in and out of Moby Dick; one of the book’s best qualities is that, once you’ve read it through, it rewards return. As sprawling as it is, the narrative is welcomingly modular — you can drop in on any given chapter for an exhilarating, elegiac, or enlightening experience that manages to stand on its own. (If you’ve never read Moby Dick, please do; and if you have, go back. It never ceases to astonish.)

Melville’s 1851 masterpiece is probably the work most commonly cited as “The Great American Novel,” but in considering this proposition, I had some reservations. The primary one is that, while I agree that this may indeed be the greatest American novel, I questioned whether it was sufficiently American. Shouldn’t “The Great American Novel” take place in America, rather than, say, on the high seas? (See map below)

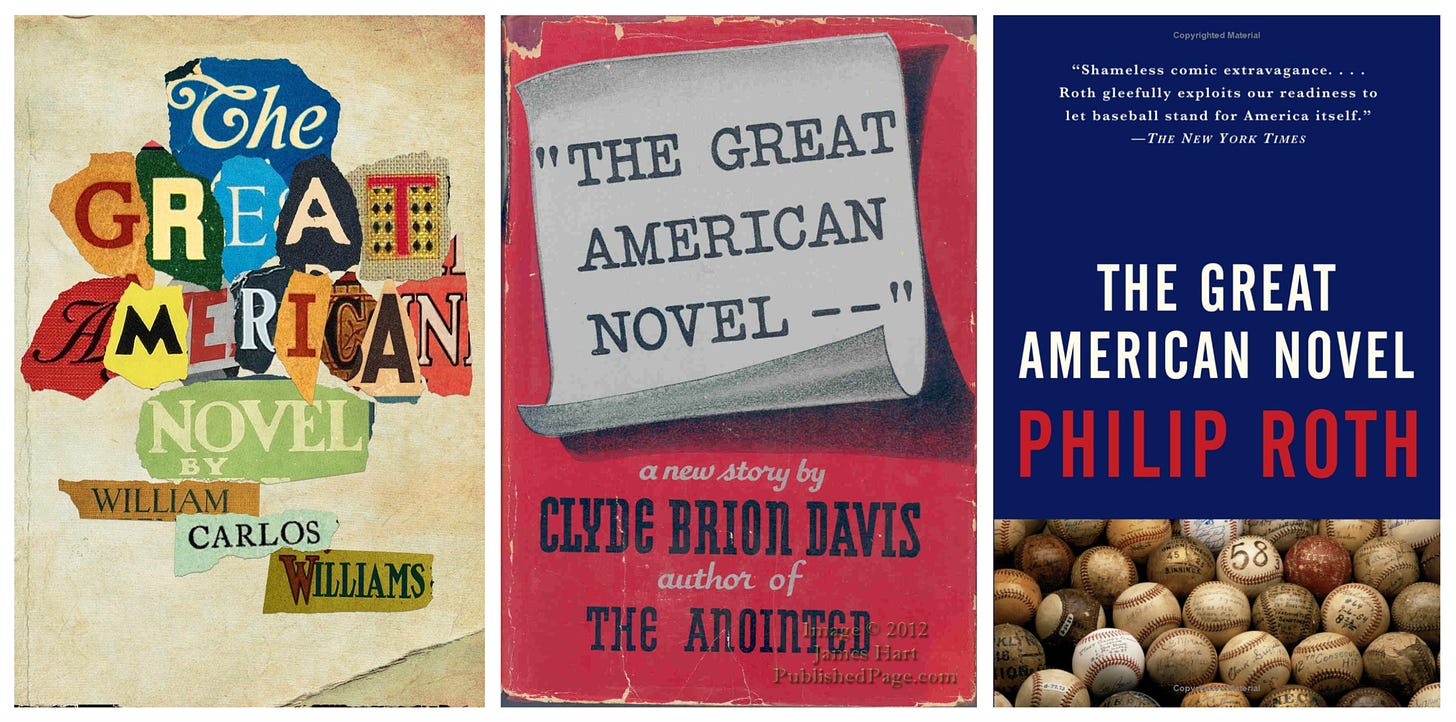

It was this question which inspired my latest excursion down the digital rabbit hole. As it turns out, there have been no fewer than three book’s titled The Great American Novel: William Carlos Williams’ 1923 version; Clyde Brion Davis’s in 1932, and Philip Roth’s 50 years ago, in 1973. While all three may be Great American Novels, none is a “Great American Novel.”

This now-clichéd term was apparently coined in a 1868 essay in the Nation, in which John William DeForest called for an American equivalent to “the tableaux of English society by Thackeray and Trollope, or the tableaux of French society by Balzac and George Sand.” After dismissing the worthiness of Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, DeForest’s pick was Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, despite that novel’s “very noticeable faults.” Melville didn’t even warrant a mention.

In fact, it’s been almost exactly 100 years since Moby Dick worked its way into the conversation — in August, 1923, D. H. Lawrence’s Studies in Classic American Literature sparked a major literary reappraisal of Melville’s work after decades of critical neglect. In the ensuing century, countless authors have set out to write “The Great American Novel” and missed the bullseye, even if they hit the target. According to Grant Shreve in JSTOR, the rough guidelines for a worthy aspirant would include the following criteria:

It must encompass the entire nation and not be too consumed with a particular region.

It must be democratic in spirit and form.

Its author must have been born in the United States or have adopted the country as his or her own.

Its true cultural worth must not be recognized upon its publication.

Herman Melville was born in New York, but that seems to be the only box here that Moby Dick definitively checks. In 2014’s The Dream of the Great American Novel, Harvard professor Lawrence Buell laid out a more expansive definition. In his analysis there are, in the words of Michael Kimmage in The New Republic, “four pathways to GAN status”: “centrality and influence” (The Scarlet Letter); “exploration of the ‘up-from’ narrative” (The Invisible Man); “regional, racial, and ethnic confrontation” (Huckleberry Finn, Beloved) “the disarray of American democracy” (Gravity’s Rainbow, Underworld… Moby Dick.)

“At least for now, the case for Moby-Dick seems to need least defense,” wrote Buell. “Moby-Dick‘s dissemination as text, and its fertility as object of imitation, as icon, as logo, as metaphor, have no more stopped at the nation’s borders than the Pequod did”

One theme you’ll notice in reading about “The Great American Novel” is that it has been an overwhelmingly male pursuit — as Joyce Carol Oates wrote, “a woman could write it, but then it wouldn't be the GAN.” But while it is true that it’s mostly been men who have set out to write the GAN (that was Henry James’s term), many of the writers who actually succeeded in the task have been women. In addition to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s status as the original title holder (at least in DeForest’s estimation), other frequently-mentioned books include Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton, Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell, and Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston. A 2021 New York Times readers’ poll named Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird as “The Best Book of the Last 125 Years,” fiction or nonfiction, American or otherwise. And in 2006, a panel of Times’ critics named Beloved by Toni Morrison the greatest novel of the previous 25 years.

Beloved would certainly make my own shortlist, alongside usual suspects such as Huckleberry Finn and The Great Gatsby and more personal, idiosyncratic picks like Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry, Norman Mailer’s Harlot’s Ghost, and—if assembled as a single volume—Gore Vidal’s Narratives of Empire. All of these satisfy the sweeping and “American” requirements, even if they appear on nobody’s list but my own.

What are your own nominees? I’ve gathered a number of different articles, lists, and analyses below to help spark some debate, and I hope you’ll share your nominees in the comments. There’s no right answer of course; arguments have been made for such titles as One Hundred Years of Solitude (“American” is an expansive concept) and “The Wire” (yes, the television series.) In 2004, Mailer conceded defeat, declaring that “the Great American Novel is no longer writable. We can’t do what John Dos Passos did. His trilogy on America came as close to the Great American Novel as anyone. You can’t cover all of America now. It’s too detailed.” (Elsewhere, Mailer gave the belt to Huckleberry Finn.)

In a 2011 article on Mailer, Richard Brody asked “why he never managed to slay the white whale and write the Great American Novel?” In fact, Ahab and the whale have often been used as an analogy for the pursuit of the “Great American Novel”. Moby Dick may in fact be the closest thing we have” — as noted above, I think it’s probably America’s greatest novel. In that sense even if Moby Dick isn’t the official “Great American Novel,” Moby Dick the character is the best metaphor for it that we have.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sword and the Sandwich to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.