A Country Indifferent to Death

To be a good American is to ignore the loss of others, or dismiss it as an inevitability

Edited by David Swanson

There’s an old saying, cobbled together from Pearl S. Buck and Hubert Humphrey and often misattributed to Mahatma Gandhi, that the measure of a civilization is how it treats its weakest members. Humphrey, who was soundly thrashed by Richard Nixon in the 1968 presidential election, more explicitly elaborated that the great moral test of a society is how it treats “those who are in the dawn of life, the children; those who are in the twilight of life, the elderly; those who are in the shadows of life; the sick, the needy and the handicapped.”

So: how does America treat those in these differing human lights—dawn and twilight and shadow?

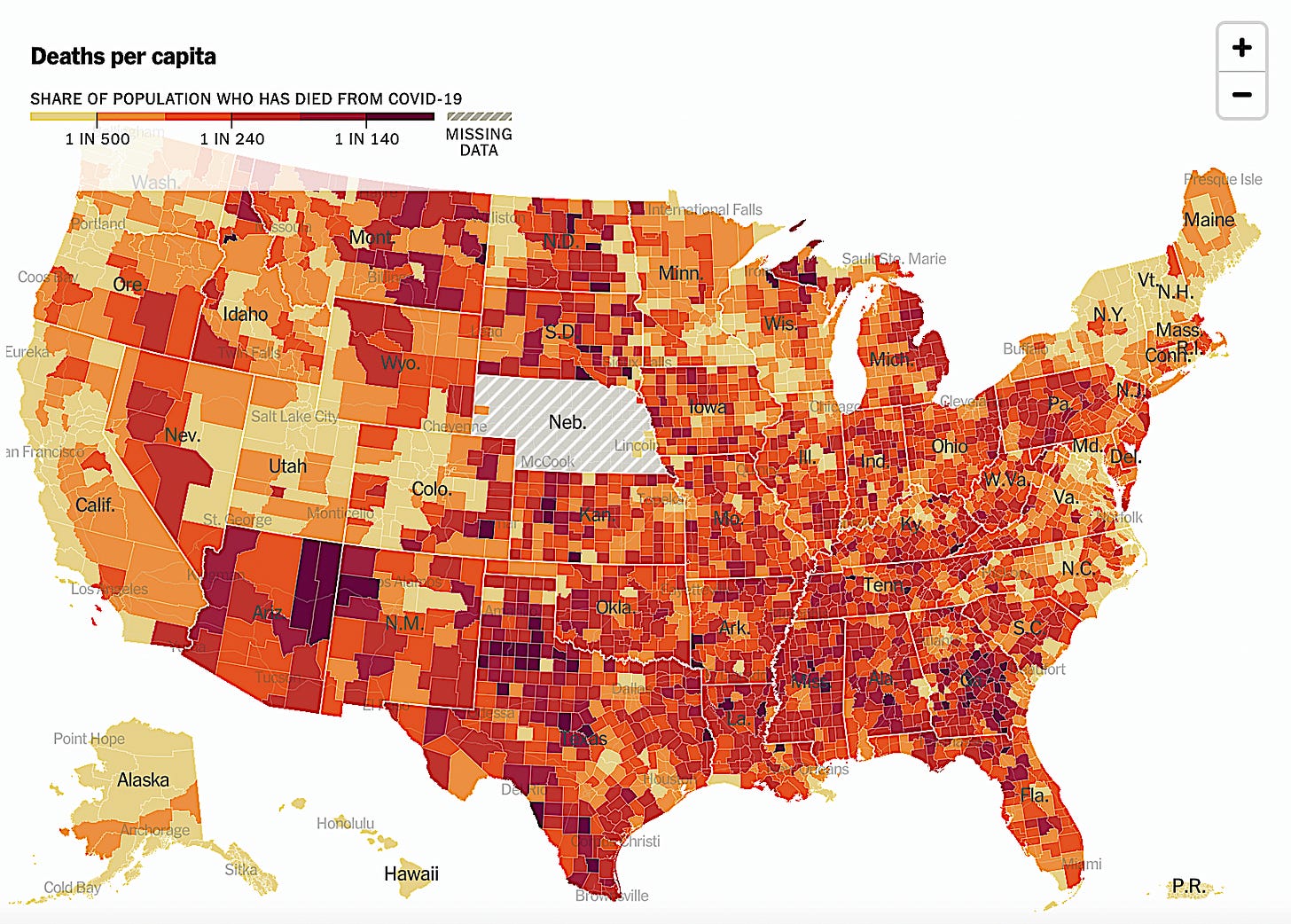

The latest wave of the coronavirus, B.A.2, coincides with a national effort—on the part of the increasingly blasé CDC and the elite commentariat—to maroon the sick and the poor and the old in a steady and rising tide of death, and at the same time to tuck it away, in bedrooms and hospital rooms, out of sight, rendering the problem as silent as the cessation of breath. There is a peculiar impatience among privileged to pretend that the virus never existed and never killed and should not be countenance—although roughly one thousand Americans die of this disease every day, and we know we passed one million deaths a long time ago, even as the official count ticks towards that grim milestone soul by soul.

Among the two million or so people in our country currently incarcerated—more proportionally, and more numerically, than any other nation by a long way—the pandemic never stopped raging, feeding on new lungs every hour. And when there is war—as there is war, now, in Ukraine—we send weapons, but we do not let in refugees; our doors stay closed even as our missiles are bestowed with open hands. You could call it necropolitics if you’d like: a politics, a society, that thrives on death, on welcoming the deaths of the frailest and the undesired, on causing death abroad by means of the entire economic and political and social and fiscal mechanics of war, on a distribution of resources so staggeringly unequal it is tantamount to extermination by neglect. A house of barred gates, bombed-out windows, cell doors, under our feet charred earth whose temperature is rising.

It is hard to think constantly of the daily bloodletting of so many, caused by the casual and unthinking cruelty of so few. But I can’t stop: It’s the nature of being a writer to keep yourself from becoming so jaded you cease to be surprised by the way things fall—to do so is to put scales on your own eyes, deny yourself the language of true impressions for the cynicism of weighing human pain and life on the tawdry scales of political fortune. To write carefully about suffering you have to look with eyes that are perennially new on suffering that is always new, even as it recurs, leaving your wounds open, to purulate and be sanded down again and again by each new cruelty. Nonetheless, like anyone with a brain in your head, you have realized by now that you live in a cruel country, a fathomlessly cruel country, gilded, rotten, cold.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

So: the expanded Child Tax Credit lapses and there’s a 41% increase in child poverty and hunger taken away is welcomed back, and no one says a word.

So people die and keep dying of this disease, and there’s no money to prevent it. There’s no money to (for example) improve ventilation in public housing or public buildings. To house the houseless in non-congregate shelters. There’s no money for care workers at all.

When a reporter asks the multimillionaire Speaker of the House about pandemic aid she responds, “people are dying in Ukraine.” And he says, “people are dying of Covid, too.” As if they had to be set against each other, competing even in death for our money.

There’s money for weapons, of course, for that country and for this one. We send weapons everywhere, and military adventurism to accompany it, the arrant military adventurism of martial supremacy—but no will to let in the people whose houses were destroyed by our weapons. Whose towns don’t exist anymore except in memory.

There are laws passed that make hard lives harder: the lives of poor women and the lives of trans children.

Laws against books and libraries.

There are aimless protests against public-health mandates that have effectively ceased to exist. The “Freedom Truckers” go drifting around the ring-roads of the Beltway and shout at phantoms and ordinary people they are convinced represent intangible evils.

Even the entertainment meant to distract us feels thin—too loud, too overleveraged, rebooted and rebooted into insubstantial slicks of iridescent oil. Instantly forgotten.

A cop shoots someone at their house. A cop shoots a naked man in the street. A cop shoots his wife. And then himself.

Everyone with any power has seemingly become a Nixon: raddled with paranoia and prejudice. Comfortable with death abroad. Or a Reagan: comfortable with the deaths of undesirables at home, of a disease that could be mitigated. Or a Biden: possessed of great power to aid, and denying that this is so; shucking off one’s own power in public while wielding it quietly for ill. To be powerful in this country is to cause and to countenance death. To be a good citizen of this country is to ignore the deaths of others or dismiss them as an inevitability.

The earth going bad like potted meat. And the storms rising.

And the complaints of the elite getting ever more petulant and insubstantial as things get worse. The gulf widening, tectonic plates shifting under our feet: an abyss between those who have and those who don’t.

So many elderly people have died. One out of every hundred. So many stories died with them. Languages, and years of life.

So many orphans.

A poet called this place our great country of money, and it is—money concentrated like tar, like the sap of a bad tree, in all too few hands. It deals out money with one hand and death with the other—it is far more generous with death, and doles it out indifferently, abroad and at home. The hissing fog of apathy gathers as if over a moor. As if over grass and heather. As if we would stay in a vegetal silence under its numbing influence and let other people die.

And will we lie down like an underbrush and hope it’s other people that die?

What else could we do, in our country of death and money, our great country of death and money, except lie like leaves in a bad season and die when we’re told to and work until we do?

And what else are we doing? And where will it end?

Who’s guilty? And who’s rich? And who’s dead?

To write well you have to ask these questions all the time. Even if you come up with the same answers, or no answers at all. You keep drinking from the bitter well and hope it will run clear someday. Until then you speak bitterly on.

Thank you for writing this. The luxury of our interconnected local and global systems allowing people to die while fluffing reports or getting bogged down in halls of power is extremely distressing to watch. I recently learned of the 500+ day siege in Tigray and their genocide within a complex civil war (within Ethiopia with Eritrea assisting). Reporting this in the media is scant and the UN shelved naming it as a genocide which would require action. Meanwhile in my adopted country of Australia people of middle eastern background are 13 times more likely to die of Covid. The infection is rife in schools. Last week a white policeman was found not guilty of murdering a 19 year old Indigenous boy. His crime was not to turn up to court because he had sorry business (cultural grieving) over his grandfather's death. Thousands of people in two states have lost homes, jobs, communities, physical and mental health due to flooding caused by inaction on stopping fossil fuel burning. The response by government to this enormous disaster has been minimal. It is local people helping each other and direct private donations from elsewhere helping, including Singapore sending helicopters and food parcels. It feels as if opaque structures encourage scarcity that leads to hatred of the other and ferment atrocities . Putin has been expert at doing this via social media in multiple countries and now we see it leads to war. It's depressing. The normal desire in most people, most of the time, to care for each other is being stifled. I try and do what I can to see, feel and act in a way that may help. Thank you again for your writing.