Land of Rotten Tomatoes

What makes America such fertile ground for cultivating violence in the name of God?

Edited by David Swanson

Religion in America has always been an unwieldy thing.

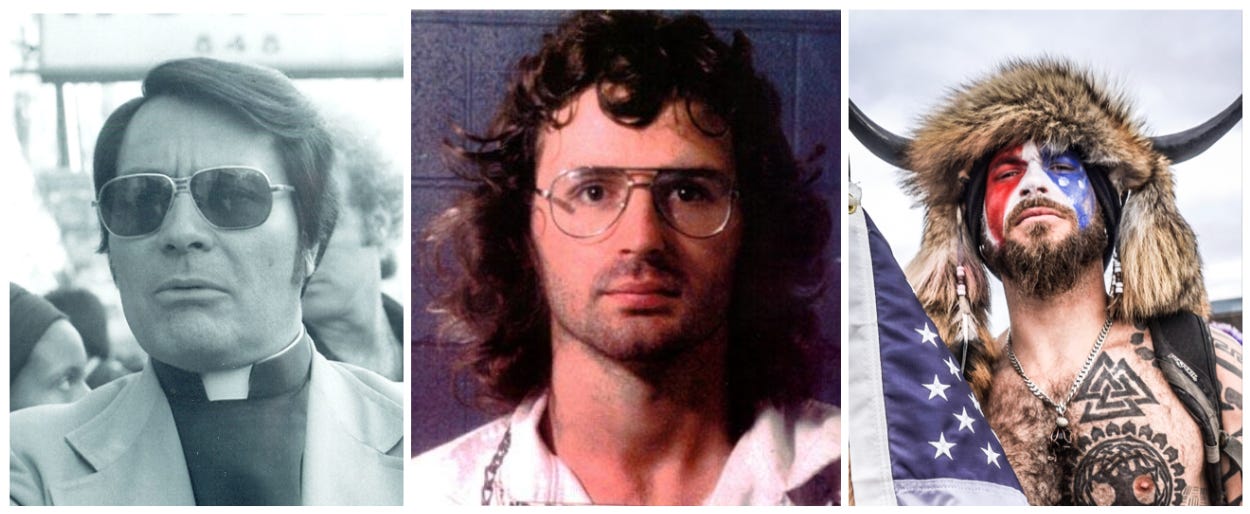

The settlers who arrived here in the 1600s were, many of them, fleeing the English Civil Wars; some were Puritans, others members of various millenarian sects. The now-blood-soaked soil of these colonies have, from their earliest days, been fertile ground for faith, the wilder the better. So many fruits were pillaged from the New World—tomatoes, avocados, pineapples—and other, stranger fruit took root here and flourished. Some have left their mark upon the whole world—Mormonism, for one; the seething quasi-religious movement that is QAnon, for another—and some are smaller, much smaller. The wounds they inflict only become visible when some tragedy erupts, like the Branch Davidians, or the People’s Temple. Even within the “mainstream” of American Christianity, a feral and barely constrained violence seems perennially on the verge of breaking through, as evinced by public and ecstatic gatherings in which crowds adopt credos like the “Watchman Decree,” written by a toothy and well-coiffed televangelist, which asserts that “because of our covenant with God, we are equipped and delegated by Him to destroy every attempted advance of the enemy.”

Some sects never get names, and never surface in the public eye at all. They merely consume a few lives, and are consumed in turn. All of that wild faith, here, in a land that seems very inhospitable to gods. Maybe that’s why it so often turns to violence.

Lately, as part of an ongoing effort to better understand the religious zealotry that shapes this country and has mutilated its lives and laws, I have cast my eyes on these smaller and stranger movements, the ones that barely register on any radar. After reading a particularly horrific guide to child-rearing as part of my book research, I’ve been examining a small Christian group, one that’s been labeled a cult by an ex-member who prefers to remain anonymous. The group sprung up in suburban Detroit in the 1990s, and its center of gravity was St. Clair Shores, Michigan—settled in the sixteenth century as “L’Anse Cruse,” the Hollow Cove. The founder of this tiny and nameless cult first sold accordions, and then became a real-estate agent.

His name was Joseph LaQuiere, and his 2014 obituary identified him as a “spiritual father” and “true leader.” His son John, who I called at the family real estate office, told me that his father had gathered followers to him—families that had heard word of his wisdom—and offered them a way to live: as Christians who observed Sabbath laws, refrained from pork, and followed certain Old Testament practices in the name of Christ. There are other Christian sects that appropriate elements of Jewish practice, although these are generally condemned as “legalistic” by mainstream Christians—a term of great scorn for the Jewish rules of observance cast off by the early church. LaQuiere also instructed them on how to raise their children. In this, he appears not to have swerved much from the breathtaking current of violence towards children that runs through a number of fundamentalist evangelical denominations; I have interviewed survivors of these childrearing practices from all over the country, and all describe internal wounds that can’t be readily stanched.

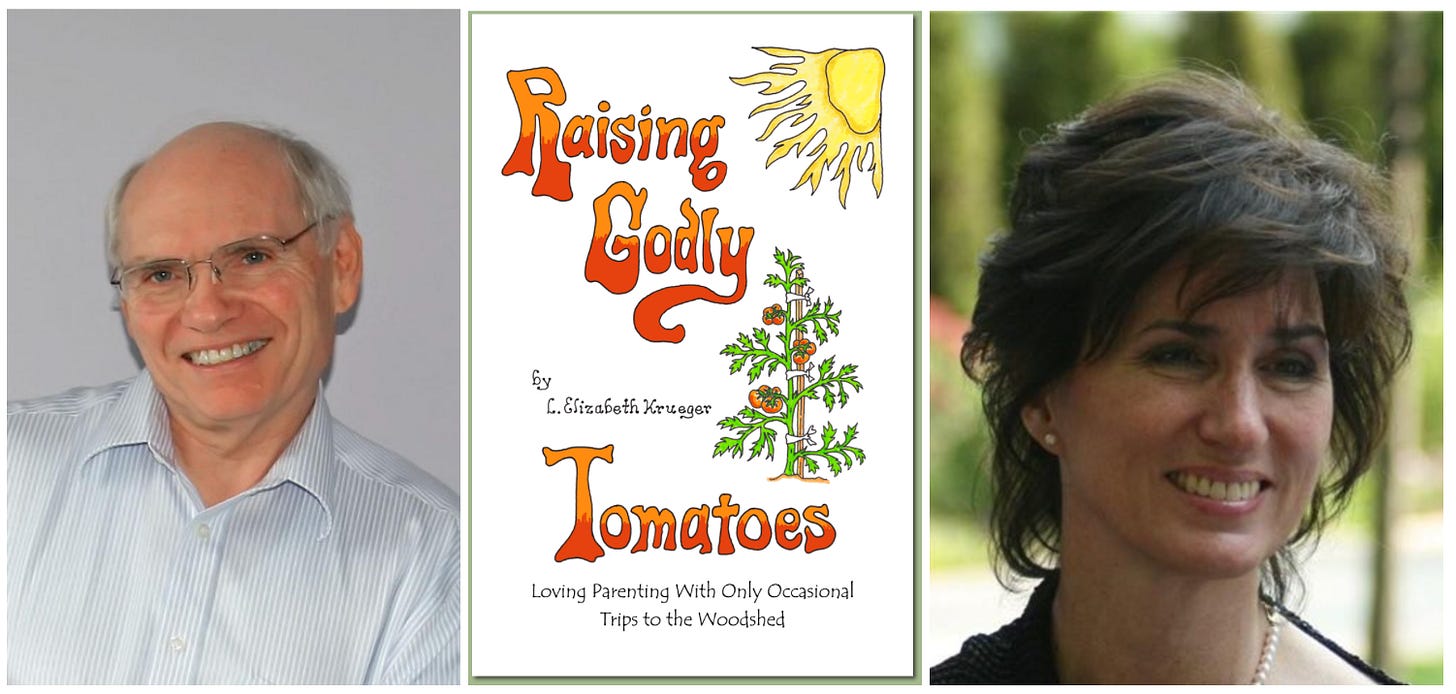

According to the testimony of the ex-cult member I spoke to, an instruction manual emerged from the small confines of the LaQuiere group, a book that enshrined Joseph LaQuiere’s child-rearing advice for the whole world to read. There’s also a rather barebones website associated with this tome, and a cheerful, sunny gardening metaphor that enfolds it all: it’s called “Raising Godly Tomatoes.” Tomatoes are a fruit of the Americas, never mentioned in the Bible, a product of the same land as the author and her spiritual mentor.

“Raising Godly Tomatoes: Loving Parenting with Only Occasional Trips to the Woodshed” is a crude-looking book, with a DIY air to it—appropriate, as it was published by “Krueger Publishing,” a name shared with its author L. Elizabeth Krueger, in 2007. The cover features bright, cheerful drawings of tomato plants, thoroughly staked and flourishing; a stylized sun sits awkwardly in the top-right corner of the cover, its rays dripping down like a Dali clock, but sharp as blades.

The book is not entirely dissimilar to other evangelical parenting guides I have analyzed, and many of its rhetorical devices are identical: the frequent invocation of Bible verse, the transparently staged “questions” from devotees of the author’s practices, and most of all, the staggering cruelty it advocates towards children, with the avowed goal of making them, not kind, not curious, not engaged, but chiefly and above all, obedient. Krueger’s chief innovation is in her persistent use of gardening metaphors. The “Godly Tomatoes” she describes are children; her method is called “tomato staking,” evoking the way tomato plants will grow profuse and unruly, then droop under their own eager, fruited weight, unless tied firmly to stakes from the start.

“Think of your child as a tomato plant,” Krueger writes. “Most parents provide little staking for their growing young tomatoes. They care for them when they are babies, but soon afterwards, begin letting them grow their own way. They feel uncomfortable assuming authority over their children… And just like the sprawling, unattended, unstaked tomato plant, there comes a point when it’s simply too late.” The philosophy—tethering your children with absolute control, battling their inherent nature into submission—echoes through a book that is little more than a manual for physical and emotional abuse cloaked in the word of God, a treatment that begins in a child’s earliest days. The contest of wills the author describes, in which the parent must absolutely and always achieve domination, echoes so many other guides in this regard; it is a triumph, in Krueger’s world, when merely asking your child to fetch the wooden paddle you will use to strike them results in complete and cowering submission. Although she does not name LaQuiere and his wife Mary specifically, Krueger notes in the introduction her emulation of “a couple whose family impressed us… we began to solicit this couple’s parenting advice (much of which appears in this book).”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

There is almost a tragicomic cruelty to Krueger’s handbook, as there is for many evangelical parenting manuals for those not inculcated in a culture of routinized child abuse. Krueger is a mother of ten, living in the Detroit suburbs less than 15 minutes from St. Clair Shores. Before giving birth to her ten children, she writes, she felt uncomfortable around children and “generally avoided them.” Perhaps she grew out of this dislike, through ten pregnancies and births. Or perhaps this is what suffuses the advice she doles out: to begin training at six months, to “ambush” your child—putting the infant in a situation of temptation, only to leap out and admonish and strike. She suggests offering no warnings. “If my child does not respond to my initial verbal instruction, I spank,” she writes. “It is quick, simple, and easily understood.” It’s part of a larger method, though one that is no kinder. “Remember this: Watch, Ambush, Repeat!” she writes, nominally to a mother whose baby has a habit of touching her houseplants.

“Mrs. Krueger’s book, and her advice, is really the somewhat-milder face of Joe LaQuiere’s teaching: the public face, if you will,” one ex-LaQuiere Group member noted in a review of the book. “She watched more violent abuse occur, and was taught that it was acceptable: babies having their faces stuffed into couch cushions to teach them not to cry—children being beaten mercilessly with ‘The Paddle,’ not once, as she writes in her book, but often 20 or 30 times. Children being dragged by their hair, thrown against walls, or dangled in the air by their throats. My own siblings endured all of these abuses, and I was made to watch.” The ex-cult member describes watching her one-year-old younger brother subjected to six-hour “training sessions” in which he was spanked every time he did not sit still, amounting to dozens of separate blows; she watched him turn into a “quiet, sullen baby who rarely smiled” and did not speak until the age of four.

The LaQuiere Group, such as it was—despite outreach to some of the principals, I found it hard to determine how many of the original cult members remain—constituted some thirty families. According to John LaQuiere, his father’s numerous descendants continue to follow his teachings, to varying degrees, although he would not discuss how those beliefs pertained to child-rearing.

This group, despite the intimate constellations of violence it nurtured for decades, is a minuscule spot on the face of American religion—like the nameless cult run by Lori Vallow and Chad Daybell that led them to kill and kill again, or the countless other sects, some named, some not, that seem to grow so thickly from the ground all over this country. Reaching toward God, mediated through unfeeling zealotry, they treat their own children as objects to be won to obedience. The public policy this mindset proffers is violence in the name of God, dictated by people whose lives are shot through with incomprehensible violence in the name of God. It is a mindset, visible across the spectrum of the Christian Right, that encourages and relishes suffering, particularly of those smaller and weaker than yourself. If this sort of faith is a plant, it’s a plant that was restrained too much, grew crooked, choked on itself, effected an unnatural profusion. The vine runs wild in ground gone soft with decay, and its fruits are poison.

My younger sister belonged to a Christian cult--Potter's House Christian Fellowship--whose pastor told her who to marry, and when her child was less than one year old, she was screaming into his face and hitting him with a wooden spoon "to drive out Satan." It was insane. There was nothing any of us could do to stop her. My mom was broken by this horror. Ultimately, my sister resorted to malicious lies about family members that tore us all apart. That cult destroyed our family. I, for one, refuse to practice any kind of organized "worship." It's all garbage. It's all for money. From the Pope on down.

It’s terrifying. I read ‘Parenting for a peaceful world’. It spoke of centuries of brutal child rearing in Europe amongst the plagues, witch hunts and famines. The cruellest parenting lingered in Bavaria where in the early part of the 20th century half of all kids died. Some from illnesses but others from beating and suicide. The author suggested that the shame and rage developed by this torture provided the basis for mass hatred turned onto the other ie Jews, those with a disability, LBTQI+ and the Romany. There is a balance between allowing people to parent as they wish and torture. These behaviours have massive society wide as well as individual harms. Thanks for writing on this subject.