All across the dreary little swamp of evangelical parenting books I’ve waded through over the past month, one woman floats to the surface again and again. She’s not a Biblical matriarch, nor any of the seven hundred wives of King Solomon, the purported author of the Proverbs that guide the punitive fundamentalist Christian approach to childrearing. She lived on the cusp of modernity, and died thirty-four years before the United States was founded. Her name was Susanna Wesley, the mother of John and Charles Wesley, founders of Methodism; she was something of a kitchen-table lay preacher in her time, and the wife of an eccentric who squandered the family’s scant funds on writing a quixotic exegesis of the trials of Job. She bore nineteen children.

Though enough of her writings survive to fill a sturdy volume, it is primarily one piece of correspondence that is quoted in Protestant circles of different denominations. The letter concerns not her role as a prayer leader nor her commentaries on the Ten Commandments or the Apostles Creed. It concerns her methods of childrearing, which she outlined in a letter to her son John in 1732:

“When they turned a year old (and some before) they were taught to fear the rod, and to cry softly. By this means they escaped abundance of correction they might otherwise have had. That most odious noise of the crying of children, was rarely heard in the house. The family usually lived in as much quietness, as if there had not been a child among them…

Drinking or eating between meals was never allowed, unless in case of sickness, which seldom happened. Nor were they allowed to go into the kitchen to ask anything of the servants when they were eating. If it was known they did, they were certainly punished with the rod…

… When a child is corrected it must be conquered. This will not be hard to do if he is not grown headstrong by too much indulgence. When the will of a child is totally subdued, and it is brought to revere and stand in awe of the parents, then a great many childish follies, and faults may be past over. Some should be overlooked and taken no notice of, and others mildly reproved. No wilful transgression ought ever to be forgiven children, without chastisement, less or more, as the nature and circumstances of the offence require.”

The evangelical-parenting industrial complex has a number of devoted Susanna Wesley fans. Notably, James Dobson quotes the 1732 letter at length and with approval in The Strong-Willed Child, advocating for parents to extinguish the “rampaging will” of their children. Larry Tomczak, in God, the Rod, and Your Child’s Bod, notes that thanks to Susanna’s discipline, John and Charles Wesley “shook two continents for the Lord.” Her influence is not limited to Reagan-era evangelicals. In his 2010 book In God We Trust: Why Biblical Authority Matters to Every Believer, Steve Ham, senior director of outreach for Answers in Genesis, a creationist ministry that provides homeschooling materials and runs two enormous Bible-themed museums, lavished praise on her as the ultimate exemplar of Christian motherhood—“the highest calling.”

The nature of that calling was stark in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Susanna lived until she was 73 years old, long enough to witness the death of eleven of her children. Eight died before the age of two, one accidentally smothered by a nurse. Susanna was nearly continuously pregnant from 1690 to 1709. It is in this context that one must consider her contention that the crying of children is the “most odious noise,” one to be rarely heard, and to be punished until it recedes into soft, broken whimpers.

Nonetheless, it is this bonneted, severe-looking woman to whom twentieth and twenty-first century evangelicals have turned to in crafting their parenting advice. It’s worth mentioning that Susanna’s most famous son, John Wesley, was rather more temperate in his admonition to utilize the rod of correction than his mother. In his sermon On Family Religion, published in 1762, he notes that corporal punishment, while ultimately commanded by God, should be used last, after all other means are exhausted. “Whatever is done should be done with mildness; nay, indeed, with kindness too,” he wrote, “Otherwise your own spirit will suffer loss, and the child will reap little advantage.”

What, exactly, the spirit suffers—or, suffering in the name of the Spirit—is ultimately the subject of this series: it is a chronicle, in fits and starts, by an outsider (or “infidel,” as one commenter put it), of pain inflicted on children. Those who wrote to me—and those who confessed later that they couldn’t, that they wanted to, that they feared to—were beaten with an astounding array of household objects in the name of Christ the Savior. Some parents were eager to perform the duty of punishment; others were less so, influenced by the social milieus of their churches and the doctrines of popular preachers to believe there was no other way to ensure their children’s salvation. For some children, the physical brutality of corporal punishment served as a primary source of trauma. For many others, the prescribed multi-step ritual—the waiting for the “neutral object” (a paddle, an oar, a hanger, a fishing rod, a dowel, a peach-tree switch), the coerced confession, the arrival at a state of brokenness indicated by a specific tenor of weeping, the subsequent coerced reunion with its embraces and declarations of love—was a source of enduring confusion and emotional pain. The books I have read span from 1970 to 2018: 48 years of the doctrine of absolute obedience, and generations of children raised in its shadow.

The stated reason for all of this pain is that children do not remain children. They grow up into morally culpable subjects of God and the world; in order to prosper, they must be taught to obey authority at all times; they must someday grow to instruct children of their own. And they have. Millions of them. Many have stayed within the bounds of the church, passing on, with each percussive blow, the doctrine of the rod of correction. Elisabeth Elliot, the daughter of two missionaries, wrote in her 1992 memoir The Shaping of of a Christian Family: How My Parents Nurtured My Faith about being struck with switches and hairbrushes beginning long before she could talk, having her mouth washed out with “a great bar of yellow soap,” and about the refusal to cry that earned her greater punishment. Her reaction was gratitude for her parents’ “vigilance”; these practices, she wrote, do not seem oppressive to her looking back, and though she is sure there must have been “nervousness and anxiety at times,” she cannot remember those feelings clearly.

Most people raised this way remain in contact with their parents: perhaps even, in a country bereft of affordable childcare, offering up new young bodies to their tender mercies. But others have left—for other churches, or for no church at all. Even bonds of blood, tested with sufficient force, can fray. Some families are the families you choose. And the children you raise do not have to be raised as you were.

“I do not have a relationship with my parents,” Erin Gentry, 35, wrote to me. “While it's probably for the best that we don't have a relationship, it's very painful just the same. They live 10 minutes away and I have nightmares that I see them out and about with my children.”

It is difficult, and sometimes even frightening, to acknowledge both that you love your parents, and that they have deeply wronged you. The sense of fractured authority, the internalization of endured experiences, can create a dissonance in the self. Those who have been taught to submit their wills may have difficulty seeing the gravity of injustice that has been done to them.

There is a peculiar loneliness to pain inflicted by your parents, who serve, in the earliest years of life, as one’s chief sources of love, nurturance, and guidance, particularly in the social context of a close-knit religious community that prides itself on its morality. Such isolation is intentional. The teaching across fifty years of evangelical parenting books is remarkably firm on this front: spanking is “an event” and it should be done in private (Benny and Sheree Phillips, in their 1984 book Raising Kids Who Hunger for God, confess that with their large family, it feels as if “much of the day is spent in the bathroom spanking the children”). The airless bell jar of private pain can descend even in public, if the religious community approves of such punishment (Sheree Phillips, recounting her three-year-old son’s tantrum after she gave a parenting class in a church: “I carried my screaming child to the restroom… I spent quite some time calming Jesse down, disciplining him for his wrong attitude, re-disciplining for refusing to receive his spanking willingly, and completing the restoration process.”)

As painful as the blows is the knowledge that there will be no rescue. Sometimes that knowledge curdles in the body and the mind, coagulates and settles into anger; bruised bodies grow bigger, and not every relationship between parent and child survives. “My mother died 7 years ago, alone and miserable after having alienated virtually everyone she ever knew,” said Kate, 50, who was struck, sat on, and pinned down while her mother prayed for demons to depart her. “I have never shed a tear, never mourned her passing.”

“I remember being yelled at to stop crying after being spanked, and feeling this burning resentment towards my parents over it, because they were the reason I was crying,” wrote Ana, 35. “My relationship with them is limited to a handful of phone calls a year.”

“I have almost no relationship with my parents or siblings beyond the occasional happy birthday text and a $25 gift for the Christmas name-drawing,” said Abbi Nye, 35, who was beaten with hoses, drumsticks and spoons, starting at six months of age. “My parents and eight siblings are all caught in various cult-like churches that emphasize obedience as a primary virtue.”

Darlene, who is in her late forties, experienced 18 months of homelessness after leaving the church and being cut off by her parents. “If I ever make enough money to have a pet project, I plan to open transitional housing for single moms leaving Evangelical families,” she said. “We nearly always lose our families, and providing a place for women to start over where they don't have to struggle like my daughter and I have had to is a dream of mine. Darlene's Home for Inconvenient Women.”

The Deconstruction Era

Many former evangelicals describe the process of leaving the church as a “deconstruction,” a term that came to Christianity by way of Jacques Derrida and a handful of ambitious, academically-minded theologians. Like so many terms, it is widely known and feared in fundamentalist circles; tentatively embraced by those in the process of leaving; and unknown entirely by most outside that world. Derrida’s famously opaque disquisitions on the dismantling of everything have given way, in the hands of impassioned writers like the late Rachel Held Evans, to encouragement. During her deconstruction, she wrote in 2015’s Searching for Sunday: Loving, Leaving and Finding the Church, she “conducted this massive inventory of my faith, tearing every doctrine from the cupboard and turning each one over in my hand.” It is, she says, “a frightening road.” (Incidentally, and perhaps relatedly, postmodernism as a whole, beyond the suave white-maned figure of Derrida, has been used for decades as a catchall bête noire in fundamentalist circles, a term for the irreverence and depravity of contemporary culture; it’s a direct antecedent to the way “woke” is used in 2021 conservatism—a term emptied of anything but scorn.)

Deconstruction, as many progressive Christians would have you know, is not destruction—but it can precede the dissolution of faith. Chiefly, it is the effort to unravel all the myriad threaded-together assumptions that make up life in a stringent faith community—corporal punishment, Republican politics, submission to God, love of one’s parents, abnegation of the self, et. al.—and to choose among them, clear-eyed. “A secret cannot even appear to one alone except in starting to be lost, to divulge itself,” Derrida wrote in How to Avoid Speaking (translated 1989). Similarly, a faith cannot be examined without undermining unquestioned—and previously unquestionable—assumptions.

Those who wrote to me have complex relationships with faith: some embrace gentler forms of Christianity; others violently oppose religion of any kind.

“I will not set foot in a church again ever for any reason,” said Johnny Huscher, 40, who recalled a childhood filled with horrific pain, and whose parents are not allowed in his home. “I am extremely hesitant to allow my kids to be alone with any adult who attends church regularly.”

“I am a Christian. My primary act of worship is in caring for others as a nurse and as a professor,” said Jamie, 50. “I believe that every human is created in the image of God and that to care for them is a privilege.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

Some of the people who wrote to me have chosen to never have children, so as not to inflict the cycle of abuse on a new generation. Others chose to have children, and to break that cycle by other means—often by deliberately and painfully overriding the lifetime of violent instinct that had been ground into their bodies. One man recounted to me a bemused dialogue he had with his lively four-year-old son, explaining to him that he didn’t know how to do this—how to parent without violence. That they would have to figure it out together.

For Johnny Huscher, having children was an opportunity to permanently sever from the practices with which he had been raised—a decision he never questioned. “If there was a difficulty in finding an alternative,” he said, “it was because I had to learn to see parenting as being about something other than domination over a child.”

“My children were not raised with violence. But it was really hard for me to learn to inhibit, and not use violence and corporal punishment, since I was raised in a family with it,” said Lisa, 60. “I slapped my daughter once, not hard, when she was a really mouthy adolescent; big mistake, I totally was wrong and apologized profusely, and she STILL talks about it.”

Other parents’ deconstruction began after they had raised their children violently. One woman wrote to me, simply: “I can’t believe I used to hit my children with a stick.”

Marcie’s deconstruction began in 2017. At the time, she wrote, “I feel like my beliefs are like a wall or stack of bricks. Each brick represents one doctrine—like one brick represents the doctrine of heaven and hell, another brick represents the doctrine of Biblical inerrancy, another represents the idea of wives submitting to their husbands, etc. … And I worry that God is mad at me for letting the bricks fall or at the very least, grieving... but the bricks are falling over and I cannot stop them.”

By then, she had raised her two sons according to the doctrines of L. Elizabeth Krueger’s Raising Godly Tomatoes: Loving Parenting With Only Occasional Trips to the Woodshed, a brutal doctrine that prescribes physical punishment, social isolation and the persistent use of shame. At the age of 18, one of her sons threatened suicide with a loaded gun to his head. He cut his own arms with barbed wire, recalling panic attacks about repentance that began at the age of nine.

“In my opinion, he likely has PTSD as a result of how I raised him,” Marcie said. “And it is too late to fix or repair things. The damage is done. I am guilty.”

For some parents, the act of having a child was, in and of itself, the beginning of the dissolution of their faith. Their instincts—their very bodies—rebelled against striking and beating their offspring; watching their sons and daughters grow up without the shadow of punishment, they mourned their own lost childhoods, and the children they could have been.

“Not a day goes by that I don’t wish things had been different for me and my siblings as children. Not a single day,” said Erin Gentry. “I’m starting to feel more comfortable parenting myself along with my kids—silently in my own mind, but acknowledging little Erin just the same and showing up for her in the ways I needed most.”

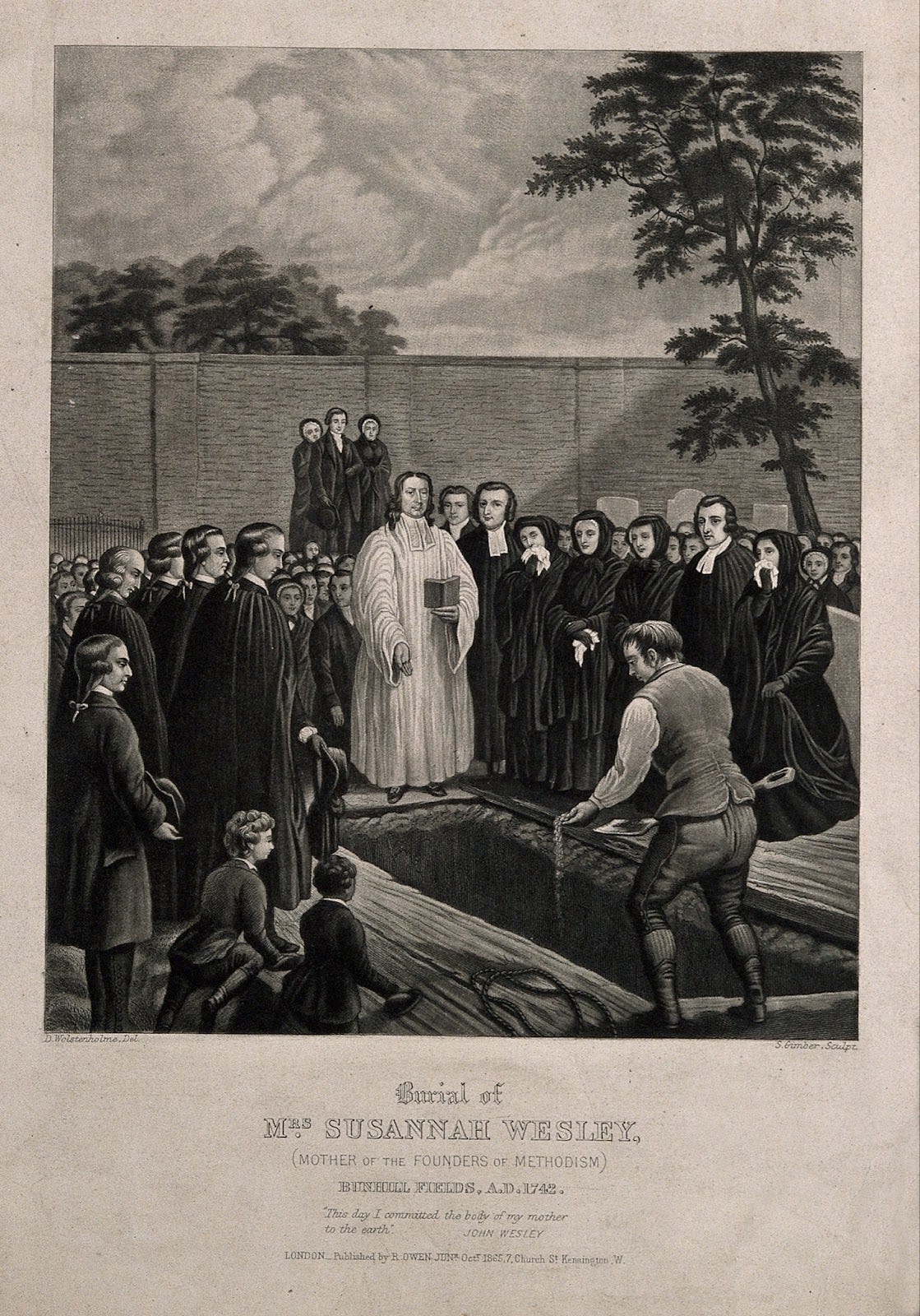

Susanna Wesley’s grave lies in Bunhill Fields, in London, its white marble tombstone spackled with lichen. “She was the Mother of nineteen Children of whom the most eminent were the Revs. JOHN and CHARLES WESLEY,” reads part of the inscription. Her husband, Samuel, is buried nearly two hundred miles away, at St. Andrew’s Churchyard, in Epworth. Of her children who died before the age they would have been taught, with the rod, to cry softly—Annesley and Jedediah, Susanna, John, and Benjamin, and four who never had names at all—little record is to be found. They are likely buried where they were born, in Epworth and South Ormesby, under the small infant tombstones that are more numerous the older the graveyard, and whose scant details are nearly always worn away. Despite Susanna’s assertion in her famous letter, only in such a grave is the will of a child totally subdued.

If you live, you can change, slowly as a root breaking a stone, or quickly. To surrender the absolution of faith, to strike out into the unknown, to parent counter to every model you had, is an act of courage; to heal from the welts and the stripes and the scars they left in your mind is an act of courage; which is not to say that it is seamless, or perfect.

“I will probably be rebuilding for the rest of my life,” Jamie told me. “As a child, I had a strong sense of justice and fairness, and that was the beginning of the rift between my childhood and adulthood; and between my parents and me. That need to make the world a more just place is still there. I am proud of it.”

I was briefly a United Methodist in high school - sort of a half-way house out of evangelicalism into more liberal and liturgical Christianity - and read a bit of Methodist history. John Wesley was married very unhappily, his wife abusive, regularly heckling him as he preached and sometimes dragging him around the room by the ear when she was angry at him at home. Charles Wesley never married - and in fact, stopped speaking to his brother for a few years after the marriage. Reading this account of their mother, I understand these anecdotes far better.

Thanks for this series. Deep and wide.

I've realized a few of the ways the routine brutalization of children could play out thru this "society" of ours, and it chills and disheartens me.

Oh to be that person whose heart is open enough to take in all the broken ones...