Morning and Evening, Pt. XXI

The latest installment in an ongoing narrative, told week by week

Previously: Morning and Evening, Parts I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX, and XX

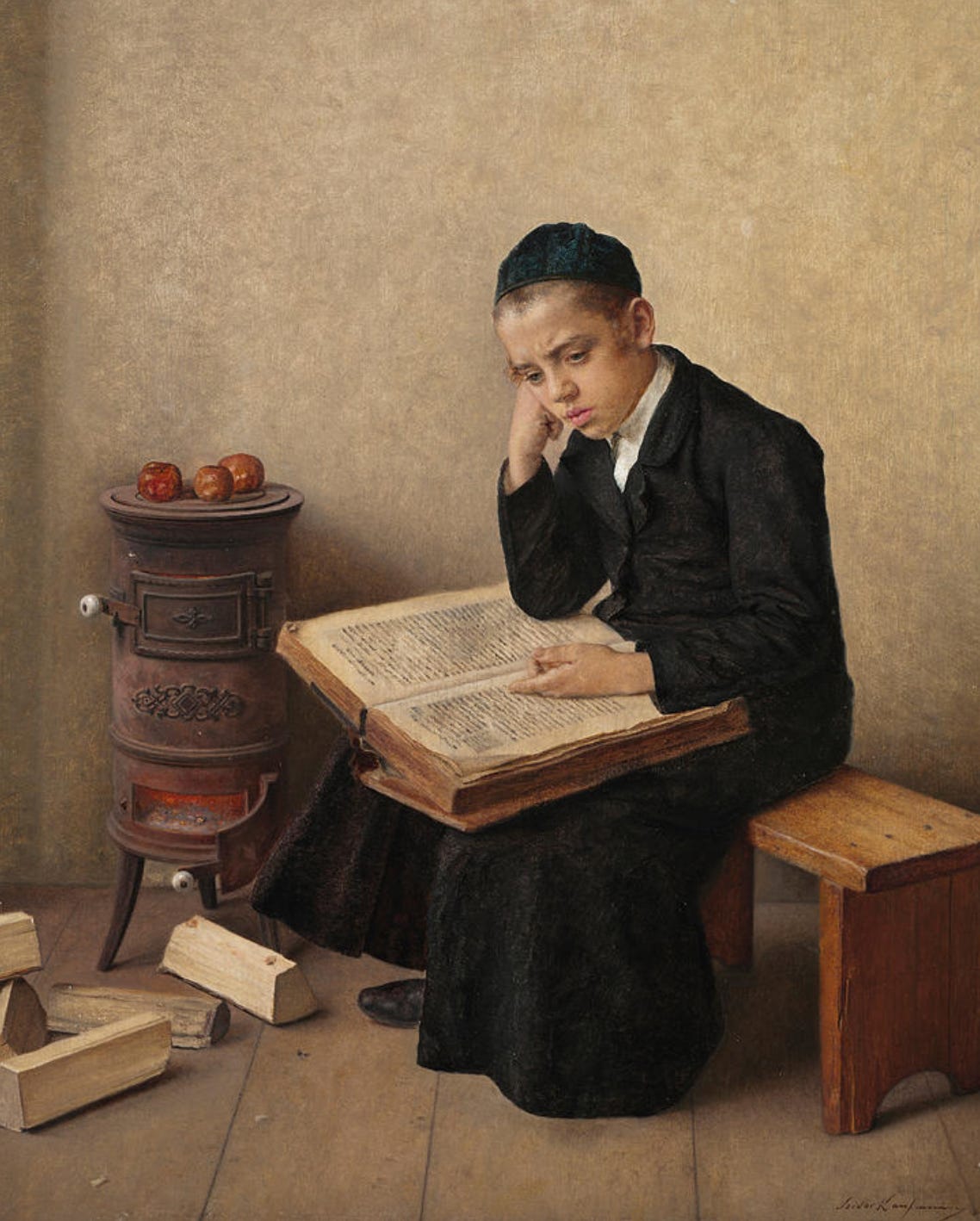

The parcels seemed pitifully small: all that he owned were a few dark clothes and the set of Talmud volumes, bound in leather, which the community had given him on the occasion of his bar-mitzvah. It was all bound in twine and it lay on his bed, which tomorrow his mother would strip of its sheets for the last time. The twine was attached to the thicker rope that looped around his shoulder and it dangled nearly to his hip. There was a great wheel of bread in the oven and a crowd of boiled eggs rising to the lip of the bowl that stood on the stove. All was ready for his journey, even the rip at the seam of his overcoat’s shoulder had been mended. He had spoken his parting words to the heder-boys and the community elders and the merchants. They had wished him luck and safety and showered him with blessings; the spines of the Talmud volumes they had given him gleamed black, the pages freshly cut, new this year from the printing-house in Vilna. A boy who comes to yeshiva with his hands full only of crushed eggshells and the last crumbs of bread from his mother’s oven is a pauper, but a boy who brings the Talmud with him to the house of study is a rich man among rich men.

Two days before he left the first snow had fallen; it was followed by another and another, but they had each melted s quickly as they came, and even now only the thinnest carpet of white, punctuated already by dozens of footprints, lay over the bare ground. To Yossel even these faint outlines seemed dear now: he could imagine the heavy boots of Mystislav the goatherd in pursuit of an errant animal, one of those who bayed and kicked when cooped in their barns through the cold. There were always these few, not always the strongest of limb, either, who turned their muzzles from the moldy hay, who bit those crowded in beside them in the stalls until all around them flanks were bleeding. One of Mystislav’s goats, two winters ago, had broken both his horns butting vainly at the barn wall; the blood from his head remained, faint now, two dark stains on the white birch walls. Mainly these goats—or foals or rams or ewes—sickened and starved, or were trampled by their fellows, but some kicked down wooden walls or rushed past their keepers and made their way to the birchwood, where some hidden green thing might sustain them if they had strength enough to find it.

As he walked around the house, readying himself for the short jostling journey to Przemyslany in the back of Taras Ivanenko’s wagon, Yossel checked the train ticket in the pocket at his heart: Przemyslany to Sokhachev, by way of Lemberg, leaving a few hours before nightfall. By a generous gift from Nathan-Neta he had obtained a seat in a second-class cabin. This meant, he had been told, he was promised a glass of tea, and that only three strangers would share his accommodations. For a few more coins he could also obtain a blanket; he had a fistful of groszy and half as many zloty for this purpose, though he had been instructed not to leave the train or make any purchase at the stops—where prostitutes cried their wares, and strings of dried fish brushed at the hips of Polish women holding bundles of meat pastries rubbed with garlic oil.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sword and the Sandwich to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.