Morning and Evening, Pt. XXII

The final installment in an ongoing narrative, told week by week

Previously: Morning and Evening, Parts I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX, XX and XXI

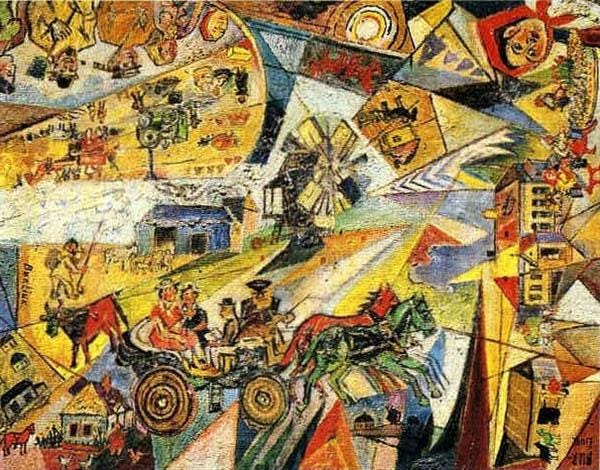

Yossel presented his ticket to the uniformed man, in a grey felt cap, who looked over his traveling papers, and made his way out to the platform, where snow piled and piled on the roof of the train, which waited, groaning softly, like a woman complaining. And then before he knew it he had boarded the train, swinging himself up the metal steps, into the cool darkness of the car. Its red carpet was worn through in places; the smell was of must and stale cigarettes. He was the first in his compartment, and he unrolled the mothy bedding, so thin and stained it seemed likely to crumble in his hands. A smell of foreign sweat was on it. He climbed to his perch on the upper bunk and pressed his cheek to the damp cloth.

Three men entered the compartment in a cluster of dark coats. In the half-darkness, all he could see of them were their beards and their eyes and the ferocious breadth of their shoulders. Slowly they stripped their coats; they began to joke with one another in Yiddish, but theirs was a rude dialect laced with Russian, and he could hardly understand it. They talked about grain prices and removed playing cards, bottles of vodka, glasses, wax-wrapped eggs and pickles from their valises, while he lay silent and grave above them.

It became clear to him that these were merchants from Odessa—they had come to arrange shipments of wheat and produce from the Carpathians, on the freight rails through Brody and down to the Black Sea. They spoke of vast sums and about the thick, earthy women of the western mountains. They laughed, and drew out their cigarettes, and lit them. Soon a cloud of reeking smoke rose up to Yossel, smothering him, while the train idled at the station. The three merchants did not reveal their names. They did not notice him at all. They were traveling all the way to ; they had been on the train a day already, and would remain for three days more. He listened silently to their half-intelligible speech. What little he did understand was coarse, as if the salt wind of Odessa had roughened it, and full of jokes spat urgently from between bearded lips. One of the merchants lit a kerosene lamp, to see the cards by, and their grins were a ghastly yellow by its light.

The train began to move so slowly he had to look out the window to notice. The rows of half-familiar trees were passing now, suddenly, a wash of snow still tumbling dumbly down from the white sky—the little slice of sky he could see out the train window. He shoved the window open lightly with his palm, taking care not to draw attention with excessive movements, so that a thin breath of wind could penetrate the cloud of stinging smoke that hovered against the compartment’s ceiling.

The trees were black in sudden thousands, illuminated by the moon on measureless feet of snow. The featureless snow was pocked and rutted only by the trunks of pines. He looked backwards, once, towards Hanachiv. A hillock caught in a shaft of moonlight receded in his vision until it assumed the shape of a silver-headed boy. The wind sounded like lips pried open around his name, calling him—Yossel!—until it died away. The train passed on, as was its task: on it had passed through hundreds of unfamiliar cities. It sawed its way over the tracks with wheels like teeth, carrying its lonesome hundreds: some away from home, and some homewards. He slept then, despite the guttural laughter below him, and the thrum of the wheels that shook him to his bones.

Dawn was breaking when the train pulled into the Lemberg station. The merchants had not slept, and they grunted as they disembarked, ready to stretch their legs in the hour or two before the idling train departed again. For long minutes after their departure Yossel lay still in the dark compartment, feeling his heart knock painfully against his chest. He clutched his parcel to his body; faintly, through the window, he could hear the calls of merchants selling to the arriving passengers. His fingers flew to the coins and bills he held, wrapped in cloth, wrapped in burlap and twine. He fished them out and shoved them in his pockets. The breath of a frigid dawn came through the open window and bloodied his cheeks with color. Only the palest light came down to him through the train tunnel, grey still, but in the cold still air he could hear a range of voices, from the sleepy murmuring of women to the sharp calls of bread-sellers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sword and the Sandwich to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.