Notable Sandwiches #14: Bocadillo, A Little Mouthful

Spain's ubiquitous sandwich is both a delicious meal and a reminder of a nation's complicated history.

Welcome to the latest installment of Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I nibble my way through the baffling and extraordinary document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. Last week: the BLT. This week: the bocadillo.

I went to Spain, once, with my mother, back in 2010—a beautiful and also terrible trip just a few weeks after I’d had my first panic attack, and didn’t know what they were yet, just that they kept happening. All other conflicts aside, we faced one mammoth problem: my mother keeps kosher, and I did when I was with her, and in Spain—a country that spent blood and lucre to thoroughly expel its Jews and its Muslims centuries ago—it is very, very, very difficult to avoid eating ham. It’s the country of ham—the Iberian pig having been cultivated and cured since before the time of Pliny the Elder, who praised their flavorsome flesh in 79 AD. After the Iberian peninsula was conquered by Moorish Muslims who did not eat pork in 711 AD, the eating of jámon became an act of political rebellion. When, later, Moorish rule fell, and the Jews were expelled, ham reemerged from the shadows of rebellion to become a crucial focal point of culinary identity, a proud Christian cultivar: a celebration of expulsion, of being swept clean of scripts written left to right entirely, and the people that once wrote those words.

As Claudia Rodin notes in The Food of Spain, hanging a ham in the window became an outward symbol of one’s Christian faith and Spanish fealty, “Perhaps that is the time when the Spanish custom of putting little bits of ham in every possible dish, including vegetable and fish dishes, took root,” Rodin writes, “as converted Muslims and Jews, as well as Old Christians, were forced to show proof of their allegiance to Christianity by eating pork.” A ham emblematized internal conquest; brought in the bellies of the conquistadors’ ships, to the Americas and the Caribbean, it became an emblem of external conquest, too.

In Madrid, there is a popular chain of restaurants called Museo del Jámon and I had to explain to my mother that it wasn’t a jam museum; downtown, there are bars with names like Mesón del Jámon, Parador del Jámon, Artesan del Jámon. Everywhere we sat, above the gull-flock crowds of white streetside tables, there were hanging ham-hocks, replete with hoofs, being carved in delicate slices marbled with fat; ham in the windows, gleaming pork in bread, chops, haunches, jowls, fatback, every orifice and limb of the pig diced up and gleaming, strung triumphantly above our heads. We ate tiny bowls of gazpacho and tinier bowls of olives and baguettes that came in baskets on the tables and we got charged for them later. It was good bread—the slouchy, open-crumbed Spanish baguette that forms the single uniting force among the many, many kinds of bocadillo.

The word is in some ways just a way to say “sandwich” in Spanish (the Spanish of Spain, which they call Castellano, after the province of Castile, and not Español, as they call it in all the places Spain stole for a time or forever). It means “little mouthful,” the diminutive form of bocado. In Latin America, “bocadillo” means “snack,” and in Hispanic communities in America as well as in Venezuela, Colombia, and Panama, it’s a dessert, a block of guava jelly. A Spanish bocadillo is made with Spanish bread—barra de pan—and you can get them with folded omelets, horsemeat, squid, cuttlefish, cheese-and-anchovies, sausage, tuna, et al. Tomatoes—taken from the Americas—are popular; so are potatoes, also taken from the New World, gulped by the Old in not-so-little mouthfuls. They’re eaten as tapas, they’re eaten at soccer matches wrapped in foil, or taken by kids to school, and here is a list of thirty-seven of the most popular kinds, giving you a glancing notion of the variety on hand, from the thinnest slices of pungent Spanish manchego to a loaf filled with mussels. One of the most popular varieties, the serranito bocadillo, is made, of course, with pork—two kinds, in fact, loin and jámon serrano.

When I was in Spain, my mother kept looking, in every city we went to, for the synagogues that had once been so long ago, and we found a few that remained what they had been, in memoriam. At the time I rolled my eyes at this—why look for gloom on sunlit cobbled streets—but now I think of the empty windows, hollow as throats, empty of prayer. My people aren’t perfect, but we don’t have to be perfect in order not to merit expulsion or death, and Muslims don’t either—kicked out at swordpoint from this city of ham, this country of ham, the whole peninsula claimed for jámon ibérico.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

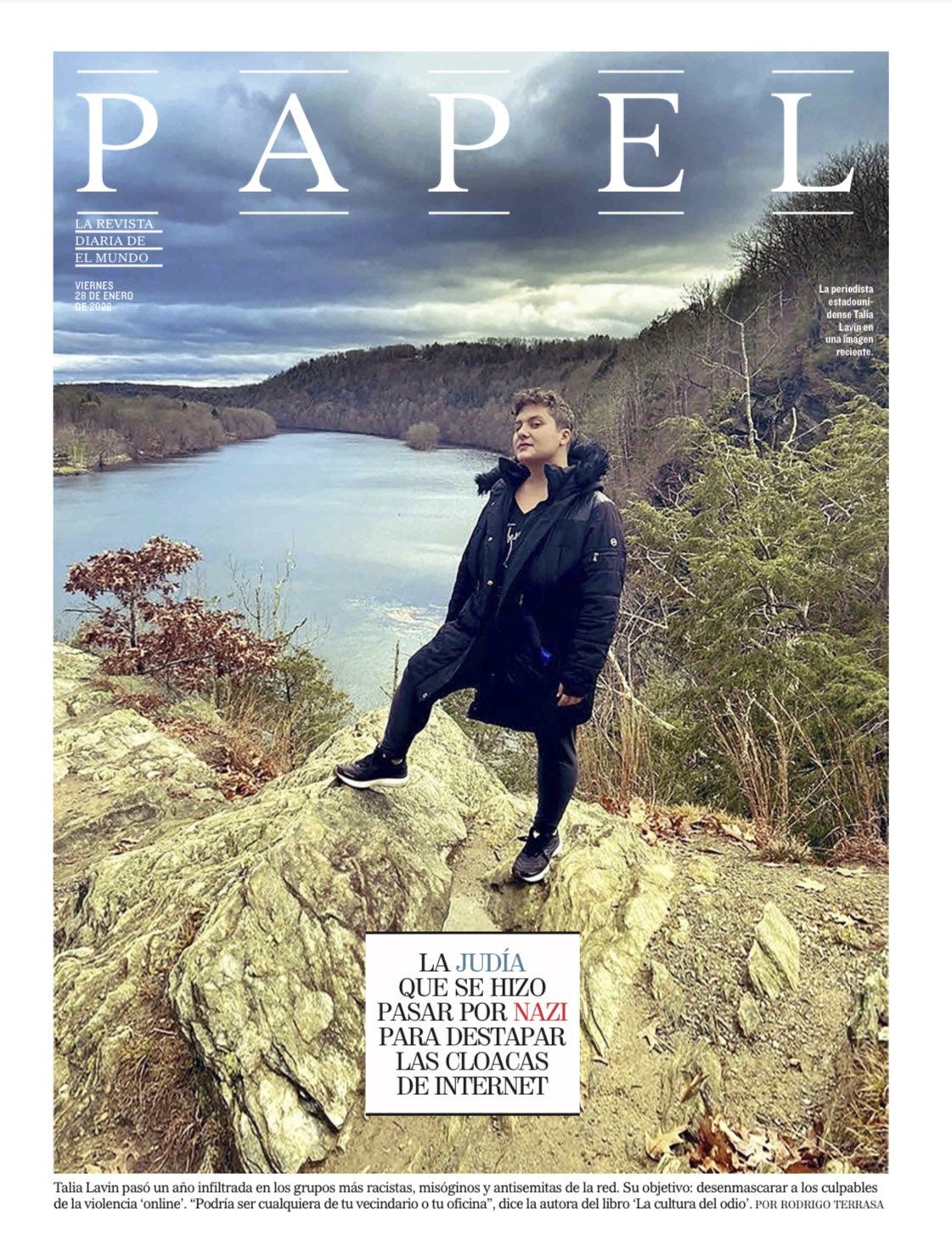

This is a grumpy and somber way to write about the bocadillo, but I’ve been thinking a lot about Spain this week. This past Monday I had the good fortune of having my book Culture Warlords translated into Spanish by Íñigo García Ureta, and published by the indie Madrid-based publishing outfit Capitán Swing, as La Cultura del Odio. So I’ve been redoing my little virtual book tour from 2020 all over again, this time made acutely aware of my embarrassing lack of Spanish, speaking to reporters from El Mundo and El País and La Vanguardia and Elle Spain and El Periódico about how it felt to be immersed in Nazi chat rooms, conferences, and channels for a year. I’ve been talking to them about white supremacy, hate, antisemitism and Europe and the past and the present, and what to expect in America, which I hardly know, except nothing very good. And I was on the cover of El Mundo’s daily magazine, and it looked like this:

Which I would be insane not to be pleased about! La Judía — The Jewess, as if I were in the process of slaying Holofernes — who crawls around the cloacas of the Internet, but here looks a bit like a lesbian heartthrob on a mountain. And this was on newsstands! In Spain! Objectively, I recognize that all of this is pretty damn cool—a dream, even, to be read in another language, to have your book be given a new life. And I am proud. And even happy, to be sought out, and to be able to answer.

Still: it’s a funny thing to write a red raw book that howls straight down into horror and fucks you up, strains your mind into pulp and your soul into tatters, and embark upon a press tour where people ask you over and over again how you didn’t go crazy writing it, and you mumble something reassuring, but the truth is you did go crazy—even before the actual FBI came to your actual door and told you strangers wanted to rape and kill you because of your book—and sometimes you’d wake up screaming, or not leave the house for a week. And then two years later to be asked all over again how you didn’t go mad, in a new language, when you’re still a half-crazed alley cat crouching in the corner of your own life, wary…

Moreover: Because of the plague and the continual hungry rampage of my madness I’m not writing this from the mild climes of Madrid or Seville or Barcelona. I don’t get to eat a warm bocadillo, which is the fully neglected nominal topic of this little essay. I’m writing in cold dripping New York, and I sit on the phone, and the elegant Spanish journalists ask me: how do you make sense of hatred?

They are doing their jobs. I am lucky to be speaking to them. And still, I think: you are calling me from a country that expelled all its Jews, offering them death, exile, or conversion. And expelled all its Muslims just over a century later, a slow bloodletting over five years, in which Spain’s long-flourishing Morisco community was purged, leaving behind walls traced with arabesques, the palace of the Alhambra, and a Christian Iberia. You are asking me how I make sense of hate, you’re asking me where it comes from, when there are people who march on your streets longing for the return of the dictatorship that ruled your country for decades just last century and killed two hundred thousand people, and they call themselves the children of the conquistadors. How should I know hate better than you, just because I wrote my little book about it? I imagine being twenty again, looking into the cold dark hollows of an abandoned synagogue, and I think about what hate does, the lacunae it creates, and what fills them, and I feel I have fewer answers than I ought to.

How do I make sense of the bocadillo? A mouthful of triumph, a mouthful of expulsion, a mouthful bit out of the world, a mouthful returned to nourish; bocadillo de jámon, an ache you didn’t know was there—answering the same question over and over, with the answer leaving you a little emptier each time, because the bread isn’t for you, because it never was, it was taken from you before you were born, and the people who took it want you to tell them why they did, why they will again; and that’s the bitter little mouthful left for you.

I had a Muslim roommate in Spain who supported the "they're promoting ham and wine on purpose" theory. Spain itself is a trip. Every decent sized town seems to have "the old synagogue" and "the old mosque", which are now typically some sort of gaudy church with terrible statues. Ask the tour guide about La Convivencia and you're met with puzzlement or a swift change of subject.

But man -- this whole write up is making me crave a bocadillo de calamari. Fried squid, generous spread of mayo, soft white bun. Delish.

Holy crap. This hit so hard. Thank you, I can't in the form of an internet comment boil down why to explain that I'm not just blowing hot air, but please know I needed this exact essay.

Simultaneously, I send all my best wishes for your ability to find peace and rest.