Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the series in which I, alongside my editor David Swanson, trip merrily through the profoundly odd and ever-changing document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches. This week: a classic closely associated with Philadelphia—the cheesesteak.

Of the score-and-a-half of sandwiches I’ve investigated for this column, a very large proportion have involved the union of cheese, meat, and bread. From the barros jarpa to the cemita, the combination of a near-excessive amount of protein, dressed in heavy coat of dairy, and served in the starchy confines of bread recurs, the way, in every country, people fly in their dreams. The cheesesteak is thus a variation on a theme, in the way that every book in English is just a sequential recombination of the same twenty-six letters, and every symphony works with the same supply of notes. These analogies are not incidental. There are many, with a particular concentration along the lower Schuylkill River, who think of the cheesesteak as its own work of art.

A very informal Twitter poll of Philadelphians found that the favored establishments are, in order: 1) whatever local spot exists on your street corner; 2) Dalessandro’s; 3) Jim’s, which just burned down. I reached out to D’Alessandro’s for comment on their place in the cheesesteak pantheon, but they did not respond, probably because I asked them for “the secrets of cheesesteak” (awkward) and also because their online contact form is principally for customers who want to order a lot of cheesesteak. And far be it from me to interrupt the slinging of the sacred meats for a few nattering and inane inquiries, all for the sake of local color that will make my consideration of the cheesesteak seem less flippant than it actually is. (I’ll note that this has been a difficult week—a relative I love is dying and I’ve been, separately, engaged in a lot of delightful but exhausting childcare, so I fully confess not to have considered the cheesesteak as fully as it merits.)

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

At the risk of offending all of Philadelphia—winding up with a brick through my window, and/or a steaming pile of Eagles-fan feces in my garden, and/or being so thoroughly canceled I’m forced to get interviewed by Bari Weiss about it—I must admit I am, at best, lukewarm about the cheesesteak. And this is not just because of my upbringing, which, strictly kosher, forbade the mixing of dairy and meat altogether.

There are other forbidden foods I’ve embraced in a life of apostasy—I am a particular disciple of the many forms of burrito, will come perilously close to diving headfirst into a carbonara, enjoy dipping my buffalo wings in ranch sauce, et cetera—but the cheesesteak has never made my taste buds and/or soul sing, or my ever-lurking lassitude stir. To be sure, there’s a comforting heft to it, and a warmth, and there’s little to quibble with when it comes to the combination of thinly sliced meat, salty cheese, and a fresh-baked loaf, plus or minus onions or peppers depending on where you’re getting one. I don’t object to the sandwich, but neither do I seek it with great passion, and when it is served with Cheez Wiz in lieu of actual dairy products, I avoid it assiduously. (Provolone, however, is another matter.)

Maybe it’s the recent heat wave gripping New York in a tight, flatulent embrace, but the prospect of food designed to be piping-hot, rich, filling and bland feels like a luxury best enjoyed in the cold. Emily Dickinson put the longing for winter during the hottest points of the year best, I think, in one of her succinct little poems: “Nay—said the May—/Show me the Snow—/Show me the Bells—”

And isn’t that always so? In the nastiest and muggiest days of high summer in my city, in which sun-soaked trash gives forth a mighty reek, I long for winter, and in the black ice and corrosive slush of February, I long fiercely for spring, and keep my eyes out for crocuses. As, in the present swelter, I am fully able to blame my lack of desire for a cheesesteak on the weather and thus avoid the ire of a notoriously choleric city, I will with shameless celerity.

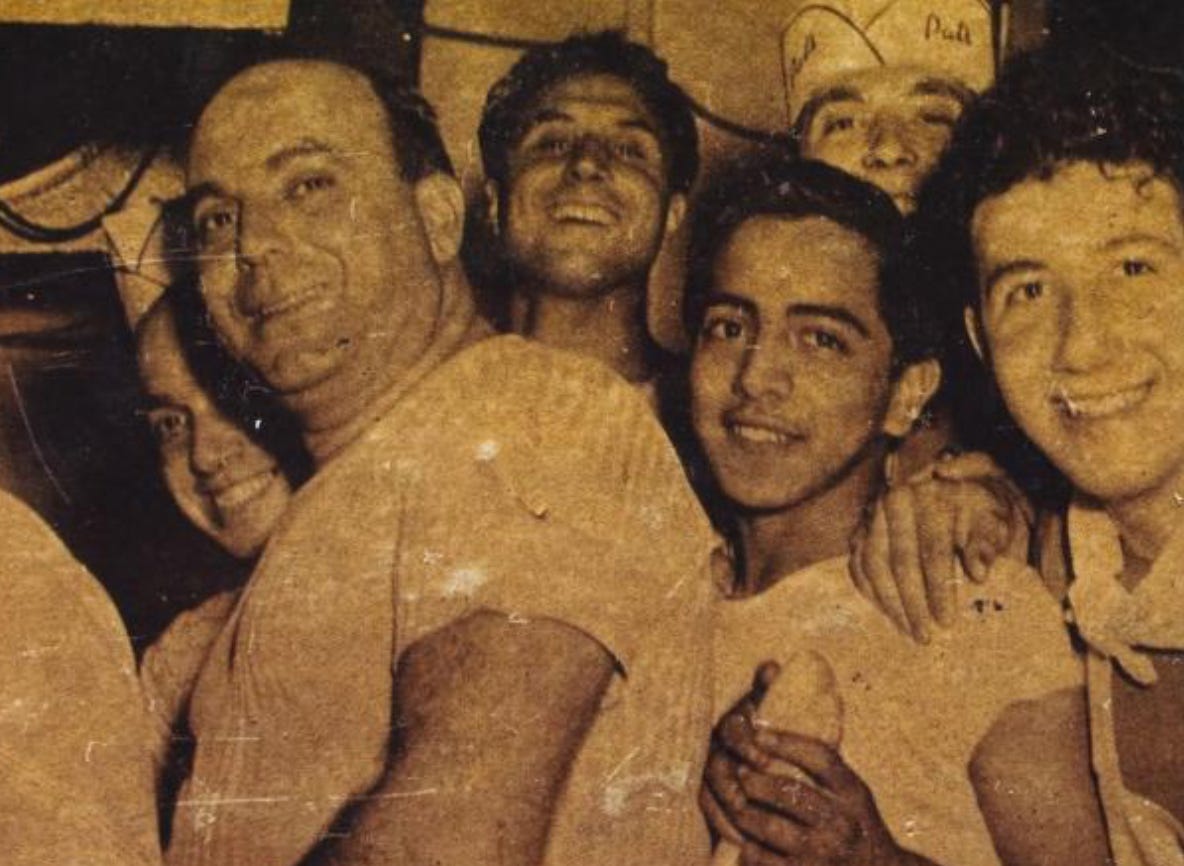

If you’ve made it this far, I feel I must offer you at least one solid bite of information, and my editor, the indefatigable David Swanson, dug up a lovely book for me—Carolyn Wyman’s The Great Philly Cheesesteak Book, published 2009, which reflects on most of a century of this sandwich. It’s generally agreed upon that Pat Olivieri, a first-generation Italian-American, grew heartily sick of slinging hot dogs on the Philly streets, started selling thinly-sliced steak sandwiches in 1932, and birthed a phenomenon. According to Wyman, who interviewed Olivieri’s third wife and great-nephew (the current proprietor of Pat’s King of Steaks), the elevation of his creation into legend had more to do with Olivieri’s talents as a showman than the innate distinctive qualities of the sandwich—he delivered cheesesteaks free to the stars of the day, like Bogart and Tony Bennett and Louis Armstrong, and drove them back to Pat’s in his red Cadillac.

The best of the anecdotes Wyman collected featured a widespread rumor that Olivieri’s cheeesteaks were actually made from horsemeat: after offering the then-princely sum of $10,000 to anyone who could prove it, he then conspicuously acquired a riding stable, presumably just to fuck with people. Pat’s remains a giant in the cheesesteak game, beckoning the city’s visitors en route from the Liberty Bell to the Philadelphia Museum of Art steps once mounted by Rocky Balboa. Pat’s fame as a tourist destination has made it a necessary stop on the local campaign trail, one that has tripped up more than one blue-collar LARPing candidate. Most recently it featured in the Pennsylvania Senate race, when fatuous snake-oil salesman Mehmet Oz wrong-headedly tried to prove his Philly credentials by first visiting Pat’s and then—at the rival Geno’s across the street—holding open a cheesesteak in his manicured hands as if it were a slightly dangerous bird, and was roundly dragged for it. (The less said about the garish, retrograde Geno’s the better.)

Olivieri’s legacy remains—in high-end iterations like the $120 wagyu-beef number at Barclay Prime near Rittenhouse Square, to the genial ubiquity of the corner-store hoagie. It’s a rare thing, and a priceless one, to create something that makes your name ring on through generations, and still rarer to have that name prosper despite the proliferation of the idea, and its escape beyond your bounds. Although I may not reach for the sandwich as my first choice—particularly in the dog days of summer—I can respect that, feel its undeniable heft, like the weight of a hot cheesesteak in the palm.