Notable Sandwiches #41: Chipped Beef

A dish that didn't come into it's own until an unknown G.I. dubbed it: "Shit on a Shingle"

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature where I, alongside my editor David Swanson, trip merrily through the strange and ever-shifting document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, after a month’s absence where I handed the reins over to David, I climb back into the sandwich saddle and examine the foodstuff most often called “shit on a shingle”: chipped beef on toast.

From the dawn of time, and certainly since the much-later advent of recorded history, soldiers have marched on their stomachs as much as their feet. If small ragged bands could subsist on plunder, grand imperial forces needed more than the land could offer—particularly as their marches grew longer, their conquests further afield. The Ancient Egyptians, circa 1859 BCE, fed their troops roast grain, beef, and four cups of wine. The Spartans had their famous “black stew” of pork and blood. Roman legions principally fed on barley, wheat, and scanter rations of pork. The Ming Dynasty, which gave over enough arable land to feed more than a million soldiers, considered the sack of enemy granaries the key to military victory.

For much of this history, the principal caloric resource of the toiling soldier was grain—easy to haul, easier to preserve, and fit to be supplemented by hunting and forage (Roman records show soldiers’ camps festooned with the bones of badgers, foxes, and even wolves). But fresh meat spoils, and so mankind has been drying it for as long as we’ve hunted it—in the hot air of desert places and the cold wind of tundras, or with salt even when salt was rare and precious. The ancient “char’qui” of Meso-American cultures prefigured our “jerky” and gave it its name, and the Icelandic sagas mention cod wind-dried on great racks called “hjell.”

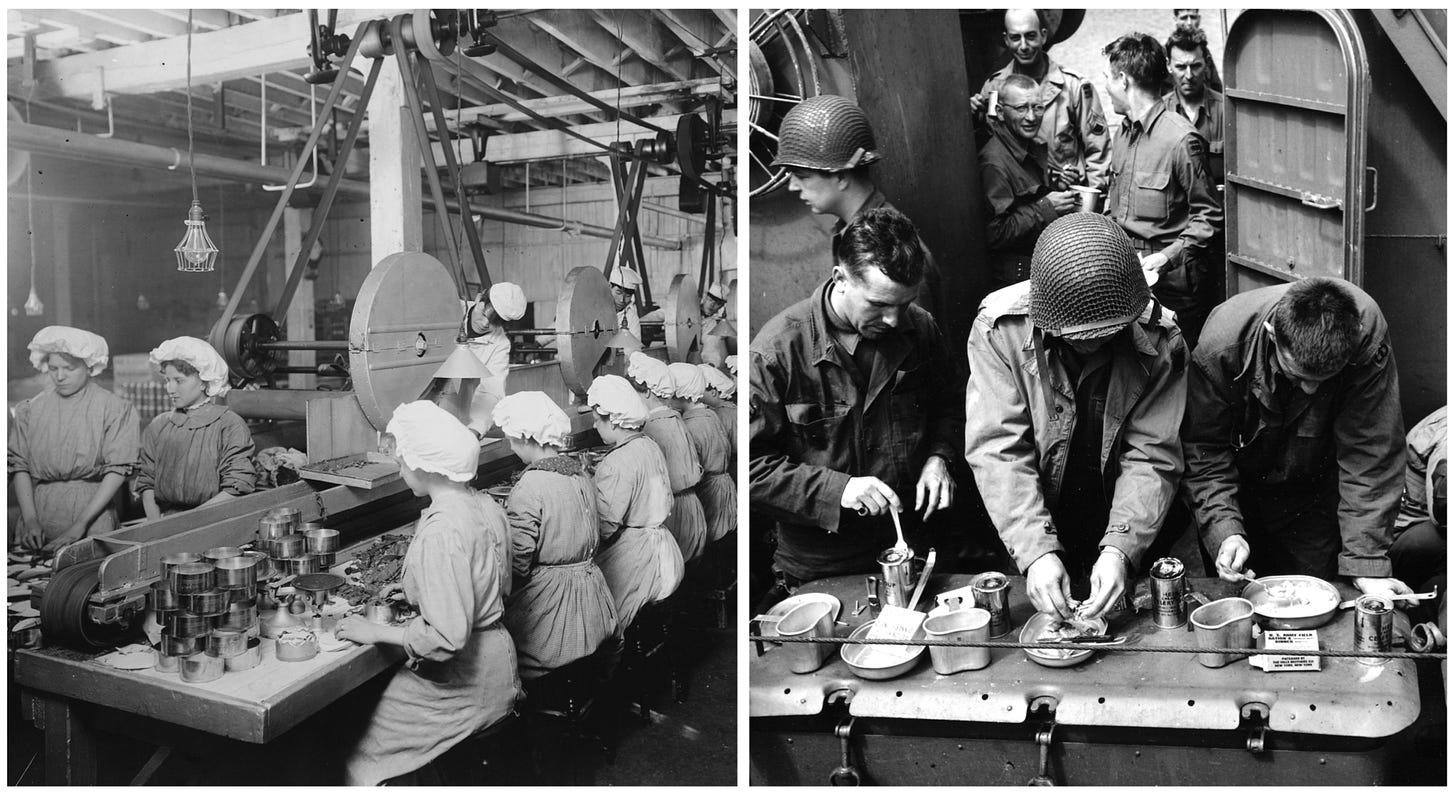

Even so, wind and sun and frost can be fickle, and it wasn’t until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with their increasingly industrialized and sophisticated methods of food preservation, that meat became more central to military fare. By 1918, according to the U.K.’s Imperial War Museums, the British were sending over 67 million pounds of meat to the Western Front each month, tinned, fresh, and frozen. American rations in World War I consisted of 14 ounces of meat a day, usually the canned, corned “bully beef” that had first come into use in the Anglo-Boer war. But all this—bully beef and tinned beef-and-vegetable stew and even the infamous “meat blocks” that formed part of British-army assault rations—were just a prelude to the most famous war food of all, a dish of such ubiquity, and dubious palatability, that it is best known by its foulmouthed soldier’s sobriquet. Creamed chipped beef on toast, today’s central subject, is most often referred to as “SOS”—shorthand both for a plea for help, and for “Shit on a Shingle.”

The recipe for the dish, such as it is, first appears in a U.S. Army cooks’ manual in 1910. Designed to serve sixty men, the recipe calls for fifteen pounds of the dried, salted beef-flake product known as chipped beef, bound with “white sauce” (butter-browned flour, milk—the poor man’s béchamel) and slapped on hard bread. It was a quintessential Depression-era foodstuff: economical, bland, mostly shelf-stable, with a sliver of salty protein to augment cheap carbs, and promoted by the dour, flavor-hating matrons of the Bureau of Home Economics.

But it didn’t truly come into its own until World War II and after, when “creamed chipped beef” moved from the frugal home kitchen to the military mess hall, and some unknown G.I. gifted it with its enduring nickname. “SOS is so closely connected with Army service that almost every veteran has memories of it—some fond, some not so fond,” Army Quartermaster Major Kevin Born told seabeecook.com, a site for military cooks and bakers, in 1999. “It's an institution as closely linked with the Army as parades, pressed uniforms or highly shined boots.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

The Navy served Shit on a Shingle throughout the 20th century as well, although they incorporated fancier ingredients, like tomatoes and nutmeg. By the Korean and Vietnam Wars, old-fashioned chipped beef was often replaced by ground beef, hamburger, mince, or even sausage. It’s still made today in military messes, where its iconic status has not receded—nor has the half-grudging, half-nostalgic attitude veterans bear towards it. “I can also attest to the fact that the military STILL SERVES THIS,” wrote Army veteran and food blogger Blake Stillwell in 2013. “They just replace the dried chipped beef with ground hamburger or sausage—they try to assure everyone it’s like a sausage gravy, but it isn’t.”

You can still buy chipped beef, today—brands like Knauss and Hormel sell cans or pouches of the finest dried flakes for $3 to $5 a pop, still a bargain when it comes to packaged protein. More to the point, SOS has been swept up in the great wave of American nostalgia that’s led to a renaissance of midcentury foods; you can still find it on diner menus alongside liver and onions, whipped prunes, and other fare that once was frugal, and now just tastes like Boomer childhood.

Naturally, SOS holds a particularly fond place for Army brats and veterans, as you can tell from a brief perusal of one basic recipe that garnered 653 comments: “My husband turned me onto this after we married 58 years ago. He ate it in the Navy and loved it. Our age has us watching salt now. I tried poaching it in hot water but it took a lot of flavor out with the salt. Next time I will give it a good rinse,” Jan R. writes. “I can’t believe I have never made this for the kids before, they gobbled it up, an old military dinner, made on the cheap often when we were growing up,” wrote Dee. Mothers, fathers, parents-in-law and grandparents brought the recipe back from front—or just grew up with it in Pennsylvania, Iowa, Kentucky, and the comments are full of mostly-fond memories.

Even though, at the end of the day, creamed chipped beef is just what Eater calls it—“a pasty gloop to be eaten over slices of toasted sandwich bread”—it’s also a piece of military culture, part of the engine of war, of childhood frugality and housewifely resourcefulness, a fount of memory as well as a fuel for destruction. Whatever you call it—“Shit on a Shingle,” or politer versions like “Save Our Stomachs” or “Same Old Stuff,” or even its formal title of “creamed chipped beef”—it seems as though the food of war is, as ever, meat and salt.

My mother used to make it sometimes on “cleaning day”. The beef came in little glass jars that we saved and used for orange juice. 1960s Kansas.