Notable Sandwiches #48: Corned Beef

The ultimate in Irish ... and Jewish ... and American eating

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the series in which I, alongside my editor David Swanson, stumble through the strange and ever-shifting document that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week: David delves into the strange history of corned beef.

— Tal

On December 16, 1923—99 years ago today—the New York Times published a story asking “Is there no jazz in corned beef?” Writing at the height of the Jazz Age, the anonymous author bemoaned the dish’s decline as a staple of American life. “We have come to the last pages of a tale which reaches back through the era of plainsmen to log cabins in the eighteenth century colonies. A tale that has dried beef for a prologue and pemmican for a footnote. A story of wars and expeditions and land clearing, leading to the hardy squatters of Harlem and so to the kitchenette. Corned beef is a mirror (though now cracked), of American social conditions.”

The author needn’t have worried. As the Times reported just two years later, a poll of 1,000,000 restaurant patrons named corned beef and cabbage as New York City’s favorite meal, beating out sugar-cured ham, chicken fricassee, and lamb stew. Today, any doubters that New York is the capital of corned beef should visit Katz’s Delicatessen on the Lower East Side, where they serve 8,000 pounds of the stuff every week. But if corned beef is emblematic of New York, this is particularly true when it comes to two ethnic groups that—traveling parallel paths from poverty and persecution in the Old World to promise and possibility in the New—reached the heights of society in America, fueled in part by corned beef. I speak, of course, of the Irish and the Jews.

Before I continue, a few notes on etymology. The art of curing beef in salt goes back thousands of years, and goes by many monikers: “pickelfleish” in Yiddish, “salt beef” in Britain, “chipped” or “bully beef” among military vets, and “corned beef” all over (this is due to kernel-sized “corns” of rock salt and saltpeter used in the curing process; the saltpeter kills bacteria and gives the meat its deep pink color). But it’s more complicated than that, as “corned beef” connotes both the juicy, tender cuts of cured brisket familiar in any good Jewish delicatessen or St. Patrick’s Day dinner, and the minced stuff that comes in cans, with a consistency closer to dog food than to pastrami. We’re not here to discuss the canned stuff, which is most familiar in America as the foundation for diner-style corned-beef hash, and is produced almost exclusively in South America. This is a sandwich column, so we’re here to talk about the corned beef that’s best served (with mustard) between two slices of rye bread, with a pickle on the side.

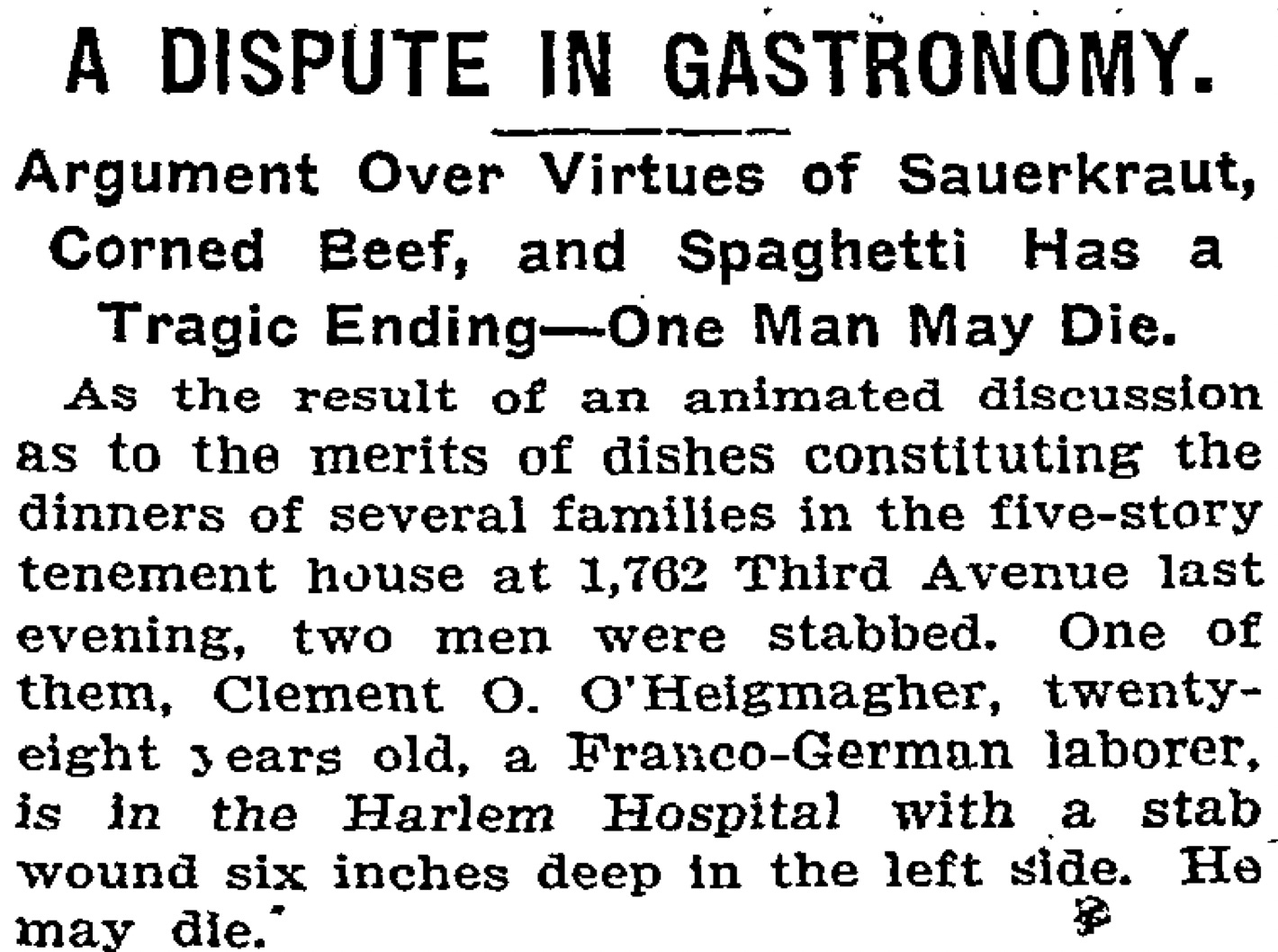

The New York Times—founded the same decade as both the flood of famine-ravaged immigrants from Ireland, and the explosion of the commercial American meatpacking industry—offers a fascinating lens into America’s relationship with the dish. The first mention, in 1857, recounts the poisoning of a Massachusetts family by corned beef, just one of countless horror stories over the next fifty years documenting the dangers of bad meat. An 1862 article reported on the arrest of Julia McDonald and Eliza McCartney for attempting to pass a counterfeit $5 bill “in exchange for a piece of corned beef.” By 1901—in a story that sounds like the setup to a bad joke—the Times was reporting on an argument over the variable virtues of sauerkraut, spaghetti and corned beef between a German, an Italian, and an Irishman. And in 1913, they published a story with the headline: “He Wanted Corned Beef: Irishman Fights When He Gets Spanish Omelet in Hungarian Cafe.”

One of the themes of those Times stories is the extraordinary lengths the Irish were willing to go for corned beef. With or without cabbage, it’s among the foods most indelibly associated with the Irish—but it’s a complicated love affair. The Irish connection to corned beef goes back millennia. In ancient times, Greek and Roman accounts tell of the Celtic affinity of salted meat, and the eleventh century Irish text Aislinge Meic Con Glinne (The Vision of Mac Conglinne), tells of “perpetual joints of corned beef” fit for a king.

By the Middle Ages, as Mark Kurlansky notes in his book Salt: A World History, the Irish were trading for salt with the European mainland, primarily for the curing of beef and pork: “Their salted beef, the meticulously boned and salted forerunner of what today is known as Irish corned beef, was valued in Europe because it did not spoil.” Although corned beef appeared on aristocratic menus, it was never peasant food. In fact, though it became one of Ireland’s biggest exports, corned beef was never fundamental to the local population, whose diet leaned more towards pork, and later, the potato. Nevertheless, the beef from cattle raised on English-owned Irish estates, and then cured and packaged in Cork City, would go on to feed the British Navy in its pursuit of global empire.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

So by the nineteenth century, corned beef and Ireland were linked on the global stage. But it would take the potato famine, and the subsequent mass migration to America, for the dish to become an actual staple of the Irish—or, rather, Irish-American—table. There are various theories as to how this happened. While corned beef and cabbage was a rare meal in their homeland, bacon and cabbage was a favorite. In America, according to some authorities, the newly arrived Irish couldn’t find (or afford) their preferred type of bacon, but corned beef—beyond their budget back home—was cheap, filling, and a reasonable substitute.

Which brings us to the other group most associated with corned beef. Like the Irish, the Jewish immigrants who soon filled New York’s tenements had a history with corned beef going back long before they fled their arrival in America. “Cured meats and sausages entered the Jewish diet during the tenth and eleventh centuries, when Jews were living in the Alsace-Lorraine region of France,” writes Ted Merwin in Pastrami on Rye: An Overstuffed History of the Jewish Deli. When the Jewish population moved East at the invitation of the Polish kings, they brought their expertise in curing meats with them. But, while “pickelfleish” became a standard item on the tables of wealthier Jews, as in Ireland, endemic poverty made beef prohibitively expensive for most.

That wasn’t the case in America, however. As Roger Horowitz writes in Putting Meat on the American Table, the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848 opened up the vast Western prairies to American cattle, launching the nation’s commercial livestock industry, and making beef cheaper then ever before. Now even the Irish and Jewish poor could afford a dish they might once have only dreamed of. And it quickly became clear to one and all that kosher butchers had a way with corned beef that appealed to their new Irish neighbors on a visceral level.

By the end of the 19th century, the kosher delicatessen was a fixture of New York cuisine, and the sandwich had achieved a heretofore unimagined ascendancy. “It may seem odd that the humble sandwich epitomized life in New York during the opulent, ostentatious Jazz Age,” writes Merwin. “But sandwiches were all the rage.” In 1926, the critic George Jean Nathan reported over 5000 establishments in New York specializing in sandwiches—almost 1000 different kinds, “made from ingredients ranging from snails to spaghetti.”

The connection between the Jewish and the Irish goes far beyond an affinity for corned beef, of course. “Others have a nationality,” observed Brendan Behan. “The Irish and the Jews have a psychosis.” No wonder that in writing Ulysses—arguably the greatest novel in Irish (and modern) history—James Joyce made the Jewish Leopold Bloom his central character. “From humble beginnings in America, these two ethnic groups rose to prominence by the middle of the 20th century,” Rory Fitzgerald noted in 2010. “By the time of president John F. Kennedy’s election in 1960, Irish and Jewish Americans were the two wealthiest and most successful ethnic groups in the U.S.”

In the United States, Irish and Jewish leaders helped establish the labor movement (the Irish have Mother Jones, the Jews have Emma Goldman). Political leaders from both groups had to overcome vile prejudice and accusations of divided loyalties before achieving the heights of power. In New York, they both went from running the city’s criminal underworld to running city hall.

That they did so fueled by corned beef is as much an American story as it is an Irish or Jewish one. There is something distinctly American in the way the commingling of New-World frontier culture with Old-World ethnic influences resulted in something special and new. As that anonymous author from 99 years ago observed, in addition to feeding New York’s 19th century immigrant population, corned beef helped sustain the nation’s pioneers, its slaves, and its soldiers. It was served at Abraham Lincoln’s first inaugural dinner in 1860, and was smuggled by American astronauts into outer space just over a century later. And today, on the Lower East Side, the Katz’s staff is still hand-slicing luscious strips of corned beef. Only now, instead of old Jewish men feeding their hungry Irish Americans neighbors, those wielding the carving knives are primarily Latino immigrants, and the diners hail from the world over. How American is that?

Corned beef, chopped liver on rye used to be a favorite of mine!