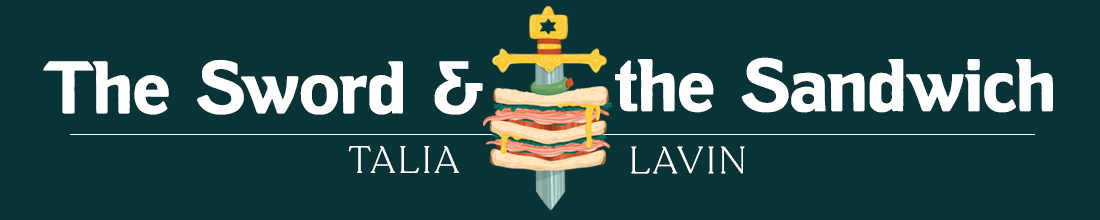

Borscht isn’t the same color as anything else. The type I had as a kid at Passover was a creamy purple, not quite mauve, not quite the color of a violet throat sweet, but close. It was beets and sour cream, and later, much later, I would learn to classify it in a broad and bewildering taxonomy of borschts, which come in infinite regional varieties. But as a kid it was part and parcel with my grandparents’ accents, to wit, thick, and Eastern European without any particular specificity, and part of a series of traditions I accepted without much resentment and without much glee.

When I was growing up Orthodox in the nineties, the Holocaust was omnipresent in my education. We had Holocaust Memorial Day slideshows of gruesome bodies stacked like cordwood, set to maudlin songs; in my own family, what Bubbie and Zaydie had endured rose quickly to the stature of family myth. In lieu of details — those were hidden in a fug of trauma — impressions filtered down to us children: the woods, the partisans, Poland, starvation. There was always a sense that the living memory of these horrors was soon going to be lost, and in the present, we were the young, hormonal soldiers against those horrors’ return. Imprecations against intermarriage were interleaved with the Holocaust slideshows: to marry a non-Jew was in its own way a violent act, our own possible future contribution to the diminution of the Jewish people, a tarnishing at our own small hands.

Modern Orthodoxy, the sect I grew up in, presents its paradox proudly in its own name. You’re allowed to watch movies and television and learn math and science, but you also daily obey a set of ancient strictures generated by people who wrote on calfskin and believed lice were animated particles of dirt. (You are allowed to kill a louse on the Sabbath for this reason.) I watched romantic movies as a kid — the cookie-cutter kind filled with the overcoming of manufactured obstacles, the saccharine, two-hour, sexless foreplay before the final kiss, two faces tilted together, often in the rain.

I can’t remember quite how old I was, although I was prepubescent, before I posed the obvious question: if I fall in love with a non-Jew, will you be OK if I bring him home? And the answer was no, a stammering, hesitant no, flush with awkwardness, but ultimately firm. I was a Jew who would marry a Jew, because “they” — the undifferentiated collective “they” I had thought might include my future love — had tried to kill us so often, and for so long. To fall in love with a hypothetical blond broad-shouldered Christian, like Matthew McConaughey in his J-Lo rom-com era, was to align myself with those forces. And didn’t I have a cousin who was named for my grandparents’ first baby, who died in those mysterious woods in Poland, with the partisans, the starvation, the snow?

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

For a long time Poland was a mythical place for me, and a metonym for all of Eastern Europe, a vast land of forebears and ghosts and snow. Some part of me knew that it was a member of the European Union and accessible by airline, but it was where horrors walked hand in hand with mythic figures: the Maggid of Dubno, the Ba’al Shem Tov, founder of Hasidism, the Vilna Gaon. There was history, and legend; the Holocaust, about which I had learned so early, was both. I knew about the Warsaw Ghetto about a decade before I knew what a euro was.

So much of our lives as Ashkenazi Jews had been born in Eastern Europe: gefilte fish, kasha varnishkes, cholent, pickled herring, the mournful tunes of the liturgy of penitence. But in New Jersey it was without context, without a true past, just a sense that this was how things had always been — even if “always” only extended back a generation. I was born the year the Soviet Union lost control over Poland, two years before it fell entirely, but the sense of that region of the world as a slightly unreal and mostly unknowable home of magic and menace persisted. (To underscore the point, I later found out that the once-Polish region my grandparents grew up in is now part of Ukraine.) In the meantime, in the new land, America, where my grandparents had come to escape all that, we ate borscht every Passover, cool purple spoonfuls that stained the tongue.

My desire to really know more about where I figuratively came from was born with a chance scrawl on the desk of a high-school crush. I’d just figured out that I liked girls — not just smooth onscreen Gentile men, or the boys that made me sting with sweat — when I encountered her on the street. I’d met her in eighth grade at a mutual friend’s sleepover, where we’d talked about books at some length, but when I saw her walking down the street in my town two years later I didn’t recognize her. I just saw her perfect curls and the curve of her hips and the sight made me stop and peer as if I’d forgotten my glasses, as if hormones generated their own fog, and I needed to stare until the haze around her resolved. In retrospect, I was lucky she thought I was staring because we’d already met.

That chance meeting on the sidewalk resolved into an unlikely friendship: I was a firm denizen of the Orthodox part of town; she wasn’t. She lent me The God of Small Things, by Arundhati Roy, and introduced me to the Mountain Goats, and told me about life in a secular school, about boyfriends. I don’t remember what I brought to the friendship, one year out of my all-consuming obsession with Lord of the Rings, but probably my flushed enthusiasm was enough. We listened to John Darnielle sing in his nasal and reedy voice about impossible loves in Texas. I was, at the time, engaging in an extracurricular study of the varieties of impossible, unrequited love. Every minute of my life was extra credit. In her bedroom, on her white particle-board desk, she had scrawled a few lines by a poet, Ilya Kaminsky. The scrawl was in green marker and the leftward droop of her handwriting was perfect to me. I looked him up as quickly as I could.

Kaminsky is mostly deaf, and I downloaded audio recordings of him reading his poems. His thick Slavic accent, the swinging rise and fall of his voice, which varied tremendously in volume, felt like the roar of a strange and beautiful animal, and when he spoke about Odessa, it was in praise of a barbaric and beloved place, a mysterious republic that drew me close and kissed me with a burning mouth:

But in the secret history of anger — one man’s silence

lives in the bodies of others — as we dance to keep from falling,

between the doctor and the prosecutor:

my family, the people of Odessa,

women with huge breasts, old men naive and childlike,

all our words, heaps of burning feathers

that rise and rise with each retelling.

Kaminsky wrote poems about poems, about the poets that had made him: Marina Tsvetaeva. Anna Akhmatova. Isaac Babel. Joseph Brodsky. Osip Mandelshtam. And so I read those poets too.

I read Babel’s “The Dovecote” and “Red Cavalry” and I thought, I’m just like his Jews: spectacles on my face and autumn in my heart. I read Mandelshtam and thought of my own insomnia, my own love of Homer. And Tsvetaeva barked her black and mournful songs at me, and I rewrote the lines over and over in my big battered overheated journal:

It's time — It's time — It's time

to give back to God his ticket.

I refuse to be. In

the madhouse of the inhuman

I refuse to live.

With the wolves of the marketplace

I refuse to howl.

All this was pretty heady at sixteen. I wanted to believe I would refuse to howl with the wolves of the marketplace, although I still wanted to get into an Ivy League college. Tsvetaeva had blunt bangs and a bowl-cut in the black-and-white photographs, and enormous, deep-set eyes. She had been writing poems dedicated to Czechoslovakia, in the year 1939. Eventually, she hung herself in internal exile. I was in desperate love with my English teacher. At the time, these seemed like analogous problems.

Somewhere between Akhmatova and Blok I decided to learn Russian. In the scholarly introductions to all their books there were dire warnings about the untranslatability of the poems. Their true words were fenced off by Cyrillic, which grinned inscrutably at me off the page, lipless little teeth. And the whole region seemed so full of sorrow and magic and madness that I knew I must enter it, and perhaps, by entering it, begin to live.

It would be a few years before I could enter the real home of borscht. I had legions of plosives to learn first, the intricacies of a foreign grammar. I had to finish high school alive, which, at the time, seemed like an open question. And a gap year in Israel, which I entered because I wanted to learn Torah, and finished long after I’d changed my mind.

During that time I encountered Maria: when we were sixteen, she and I had attended an arts camp for Jewish teens. She was a child of Russian immigrants to Israel and had schlepped her violin to Massachusetts. Years later, when I came to visit her in Haifa, she invited me to her apartment. Her mother made me meat blini, and yes, borscht —not the phlox-colored aperitif my mother had served, but something red, meaty and steaming. Her father smiled broadly at me all night. They had a very fat white cat named Jerry. I could not speak a single intelligible word to Maria’s parents (or to Jerry, for that matter). But in parting they gave me a copy of Evgeny Onegin in Russian, and Maria wrote me a dedication: By the next time we meet, you’ll be able to read this.

The truth was it would be a very long time before I could read Pushkin, and, even now, I can do it only with the aid of a dictionary, painfully slowly, with my lips moving the whole time. But in the interim, I walked in Odessa among the catalpa trees, watched the Black Sea lap at its famous steps; I saw the great memorial colossus of Volgograd. I swam in the Don River, drank vodka in the ruins of a Khazar settlement, saw the sacred groves of Mari-El. I entered the house where Boris Pasternak was exiled, and the house in which Tsvetaeva was exiled and hanged herself, in the town of Elabuga, in Tatarstan. I disassembled the Russian language into its constituent parts, reconstructed them in my mouth, phoneme by phoneme.

And I learned how to construct a borscht, how to layer beets and beef, onion and garlic and steam, how to let them simmer until they were heady as wine. In the bottom of the bowl, at the end of these journeys, there was some knowledge about where I came from, though I only redoubled my belief that these places carry their own darkness and their own magic. That knowledge is a hot, crimson and pulsing thing, a soul, a rough kind of music, a bracing draught against the coming and constant cold.

This was lovely :) I just discovered your substack publication this AM, but this post was a scary relatable amalgamation of many of my disparate interests (tMG, Judaism, Cooking, Russian Lit). Very much looking forward to seeing more!

You are a deeply open-hearted and brilliant writer. I am awed by your love and and your power to express it. Not just here, but everywhere. This essay went directly into my soul. Thank you.