There's No Such Thing as a Lone Wolf

What Kyle Rittenhouse, Dylann Roof, and Timothy McVeigh have in common

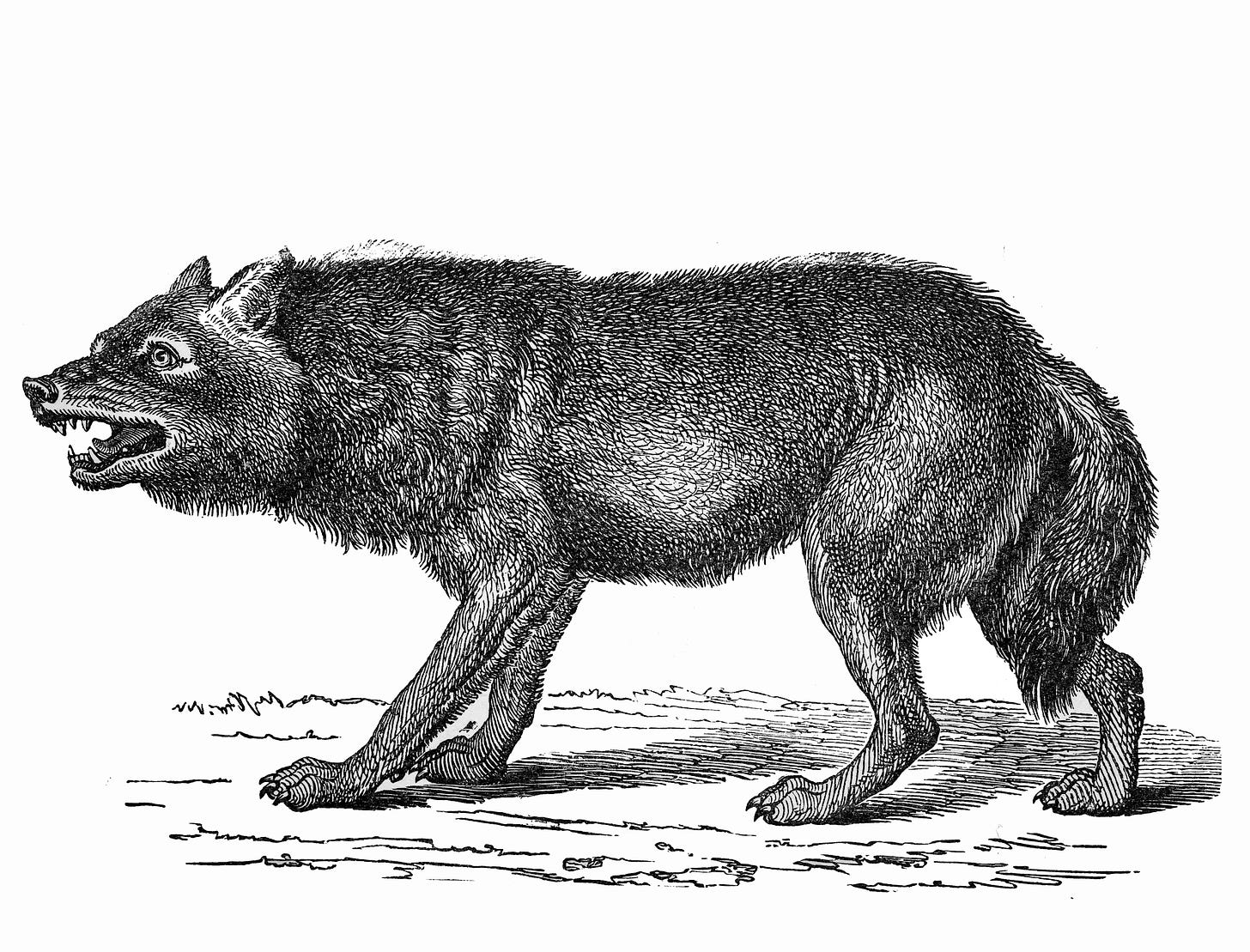

Humans tell a lot of lies about wolves. Having lived for so long on the outskirts of civilization, only interacting with man in times of dire necessity, wolves are particularly susceptible to anthropomorphization: always a threat, a howl on the wind, preying on the imagination. An early and notable aphorism that gave human features to wolves comes from the Roman playwright Plautus (254 BC-194 BC): “Lupus est homo homini, non homo, quom qualis sit non novit"—“man is not a man but a wolf to another man, before he knows him well”—an attacker of strangers, all teeth and no civility. The proverb (shorn of the qualifier applying solely to strangers) was repurposed by Erasmus, the great sage of the Low Countries, and the notion has endured—over two thousand years after Plautus’ death—that our often uniquely vicious behavior towards one another stems from our animal selves, a surfacing of the natural cruelty of wolves.

We flatter ourselves. The truth is that wolves live in complex social structures, the pack a kind of extended family, consisting of a mobile, furred unit of siblings, aunts, uncles, and cousins. As groups, they mate and protect their young, defend their territory, live in dens dug six to fourteen feet into the earth. Still, in recent years an alternate lupine metaphor has attained a certain ubiquity: the figure of the lone wolf, the man (it is usually a man) who commits an act of staggering violence, a disruption of the common sphere, frequently resulting in deaths, sometimes on a mass scale. The term “lone wolf” has been with us for centuries, historically used as a term for an iconoclast or solitary individual. For example, in the wildly popular mid-1950s TV series “The Lone Wolf,” a debonair jewel-thief-turned-detective travels the world fighting crime and finding love. It is only in the past few decades that the sobriquet has achieved its grimmer meaning, the kind plastered in newsprint and etched in acid on grieving hearts. Concurrently, it has skyrocketed in usage, a swoosh-shaped curve encompassing the past half-century, and still climbing.

We know the names of our lone wolves—Dylann Roof, Kyle Rittenhouse, Timothy McVeigh, Cesar Sayoc, Patrick Crusius. We can picture their faces, or remember the places they turned into synonyms for violence—Oklahoma City, Charleston, Aurora, Kenosha, El Paso. Perhaps it comforts us to imagine that they fundamentally acted alone, out of an combustible internal alchemy of vague influences. But it isn’t true. They were no more alone than wolves are in nature—which is to say, they emerged from one pack, and sought another.

In nature, lone wolves—which comprise about ten percent of the wolf population in any given year—are better known by conservationists as “dispersers.” They are typically young adults who travel solo, dozens and even hundreds of miles, in search of more viable mates and promising rangeland. Though they cross highways and whole sierras and slink through human settlements without company, these wolves are not technically “lone”: they actively seek out new companions, and the potential to found a new pack of their own. Many of them die—traffic and poison, cold and bullets—before they find their promised land and company. But that’s what they seek. In this sense, and only this sense, they are similar to the terrorists we decry: their actions have purpose, meaning; they emerge from the logic of a group, and are meant to gain approbation and benefit.

Kyle Rittenhouse, the teenaged exoneree last seen smirking beside the aged rictus grin of the disgraced former president, was the antithesis of a lone wolf: he arrived in Kenosha as part of a nationwide vigilante movement that arose in response to the racial-justice protests of summer 2020. Moreover, he was not the only man prowling in fatigues, heavily armed, in Kenosha that night. Driven by right-wing propaganda willfully and falsely depicting every American urban and quasi-urban area—every area with Black people in any number—as besieged, engulfed in flame, Rittenhouse had seemingly come to believe he was protecting America. He was encouraged to think so, encouraged to think that he was acting as scout for a pack, then protector, though what he was guarding was a used car lot.

Dylann Roof’s desire to kill Black people emerged not only from the sweltering suburbs of Columbia, South Carolina, but from centuries of racism (he was an admirer of Cecil Rhodes, the famously brutal British colonialist, calling himself “the Last Rhodesian.”) What Roof wanted—Black death in the service of the white race—was not uncommon, or particularly unique, in the history of his state, or his country. “I felt like I had to do it, and I still feel like I had to do it,” he said, tonelessly, to the jurors, after 573 days awaiting trial for the murder of nine members of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in 2015. “In South Carolina, those men never disappeared, were there always, waiting,” wrote the journalist Rachel Khadzi Gansah in 2017, in her masterful profile of Roof. “It is possible that Dylann Roof is not an outlier at all, then, but rather emblematic of an approaching storm.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is an exploration of serious extremism and serious sandwiches. To support this work and access all future content, please consider a paid subscription:

The most famous modern antecedent of these very young men, Timothy McVeigh, can be said even less to have acted alone. Leading up to 1995’s Oklahoma City bombing, in which 168 people died, McVeigh was actively involved in the white-power movement. One collaborator, Terry Nichols, was even sentenced to life in prison for conspiring with him, though Nichols’ name is rarely mentioned in passing references to the bombing. Other accomplices were sentenced, or implicated: Michael Fortier got 12 years for failing to inform authorities of McVeigh’s plans, and his wife testified against him in exchange for immunity. There was a conspiracy to load that truck with explosives, one thinly veiled, hardly buried at all. Two weeks before the bombing, McVeigh was in contact with members of the white-supremacist compound in Elohim City, Oklahoma, where members of the violent bank-robbing gang the Aryan Republican Army hung out. One may call McVeigh and Roof and the others—the trigger-happy young men from the mug shots—not lone wolves but dispersers, seeking out new territory in the hearts and minds of their myriad admirers, creating, through the unignorable sacrament of bloodshed, new receptivity to old and cruel ideas.

If you are convinced all this is a matter of online self-radicalization, a passing storm or the hollow lightning of midsummer, consider the multiple interstate kidnappings of children facilitated by the QAnon movement. Or the Querdenker (“lateral thinker”) movement in Germany, an unlikely salmagundi of blond-dreadlocked vegans, irate moms, and swastika-waving neo-Nazis who have taken to marching through the streets of Berlin (and storming the Reichstag) to protest vaccine mandates. In practice, as the writer Musa Okwonga put it, they are creating a reality in which “marching alongside neo-Nazis could, for many people, now become the new normal.” Consider, too, the storming of the Capitol on January 6th: how close it came to succceeding, how many people arrived alone and converged, how many others came in convoys, pulsing with the same rage and the same lust for orgiastic violence. If anything, the new normal is a continuation of the old hatreds, just more densely interconnected. New packs of lone wolves are being born every day.

Of course, it is unfair to wolves and storms to compare such people to them: a wolf in its den, even a wolf stripping an elk to the bone, is a creature whose goal now is to guard its young, to find safety, to survive in a world pitted and shorn by men. A storm is a haze of electric particles and water, guided by wind and warmth and sea currents. A man is a man when he chooses to pick up a gun. If he is lonesome he may picture the claque that will crown him with haloes after his killings: and that is a uniquely human urge, to create graven images, to deify. He does not, in his moment of ecstatic extremity, picture himself alone; he pictures himself as part of a greater whole, a movement, the hand that shoves the boulder down the hill, and starts the avalanche.

"He does not, in his moment of ecstatic extremity, picture himself alone; he pictures himself as part of a greater whole, a movement, the explosions he creates necessary infusions of kinetic energy, the hand that shoves the boulder down the hill, and starts the avalanche."

This is some good writing.

Elohim City!! Those weirdos got swept under the rug so fast.