White Supremacy's Warped Rationale

The Buffalo shooter wasn’t deranged. He ascribed to a coherent ideology.

In the aftermath of any mass slaughter in this country, the conversation turns, in desultory fashion, to the issue of mental illness. Tucker Carlson, hastening to dismiss widespread recognition of the fact that his show’s white nationalist politics echoed those of the shooter’s, who he dismissed as a “mentally ill teenager,” the sentiment issuing forth from Carlson’s angry red face like ooze from a ham. The Wall Street Journal’s Opinion section called the shooter “deranged,” asserting that “mental illness seems to be the most significant common denominator” in mass shootings. Derangement is always postulated as the first-line cause for why a man would pick up a gun and set out to kill as many people as he can. And it is a tempting explanation. It’s soothing to imagine that only an extraordinarily warped mind could engage in such acts—even when they have avowed, specific political motivations.

The truth of the matter is that Payton Gedron, who killed ten and wounded more in a Tops supermarket in Buffalo on Saturday, felt assured that he was acting in the interests of a coherent and thoroughgoing worldview: he is a part of the white supremacist movement spouting its catechisms about “white genocide,” an ideology with tens of thousands of adherents around the world, painting all nonwhite people as not only inferior but threatening, and postulating that behind it all is the eminence grise of the Jew. White supremacist ideology serves as a means to explain the modern world, even while shunning it. While Gedron appears to have been radicalized online, the world of far-right Internet extremism exists in parallel with the radicalization of the country's political right as a whole. (I wrote Sunday for Rolling Stone about the role of this rhetoric in the mainstream of the Republican Party.) The ethno-nationalist movement plays powerfully on the natural human emotions of those who buy in: on their loneliness, on their desire for purpose, on their need for a sense of identity and community. It is important to understand the mechanisms of white supremacist recruitment—its mass appeal online, given the lethal power it has to drive massacre after massacre—and in order to do so, it is necessary to take a look at the intertwined prejudices that drive the movement forward.

When Payton Gedron set out to kill, he deliberately targeted a store frequented by Black people, in a Black-majority neighborhood. It was, he wrote, the location with the highest percentage of black people “close enough” to where he lived—some 200 miles from his hometown of Conklin, New York. A Discord transcript, totalling nearly 700 pages, detailed seven months of increasingly intricate planning. He wrote a racial slur on his gun, and killed churchgoers, the father of a toddler, respected elders, turning a supermarket that had been a community hub into a site of slaughter, and leaving grieving families in his wake.

Using the strange calculus of the movement that radicalized him—the white supremacist movement—Gedron claimed, however, that his actions were not motivated by hatred of Black people. Yes, they were the “replacers” whose very existence threatened the white dominance of the United States; crime-prone and intellectually inferior, as proven by fear-mongering articles and dubious scientific studies. But black people were not the ultimate enemy, the ones Gedron and his compatriots ultimately aim to destroy. In the manifesto’s self-administered Q&A, Gedron felt the need to defend himself against the preemptive charge that he had not done his duty to the white race by attacking Jews. He explained that it was necessary to first eliminate nonwhites, with their threateningly high fertility rates. But there could be little doubt that the true orchestrators of “white genocide,” or “great replacement theory,” are the same shadowy figures that have haunted Western conspiracy theories for a thousand years. “The Jews are the biggest problem the Western world has ever had,” Gedron wrote. “We can not [sic] show any sympathy towards them again.”

The reason for Gedron’s hyperfixation on the nefarious Jewish influence—including pages and pages of collaged memes alongside aspersions against the intellect and character of Black people—is a potent example of the function antisemitism serves. Although white supremacist rhetoric pulses with unabashed desire for violent dominance over nonwhite people, any movement’s ability to grow and influence minds rests on the narrative it employs. And the emotional bedrock of the white supremacist movement’s recruitment tactics—the myth they push forward—is a story in which white people are oppressed by powerful, cunning and relentless enemy. As Jean-Paul Sartre put it in 1944, “if the Jew did not exist, the antisemite would invent him”: the Jew in white supremacist rhetoric is a creature of infinite power and malevolence, seeking to destroy the white race at all costs.

“If we look at antisemitism and anti-Blackness as a combined bigotry, an important red thread would be the conceptualization of both Jewish and Black people as irreconcilably alien,” Shafiqah Hudson, a freelance writer and researcher who has tracked online anti-Black sentiment since 2014, told me. “They believe Jewish people are deceiving and manipulating Black people. Jewish people are framed as an ancient enemy, and Black people are framed as requiring policing and control.”

According to this mindset, the Jew is the mastermind who wants to dilute white racial stock by promoting miscegenation, feminism, trans and gay rights, and above all, civil rights for nonwhite people: all the objectionable parts of a modern society can be laid at the feet of the Jew. This deeply racist worldview holds that racial minorities lack the intelligence and drive to direct their own fates; Jews control them, with innate racial cunning. And so the ethno-nationalist can cast himself as a lone voice for his race, working to undo the malevolence of an incalculable power: a hero of his time, a freedom fighter, who spills blood to get even against intolerable injury.

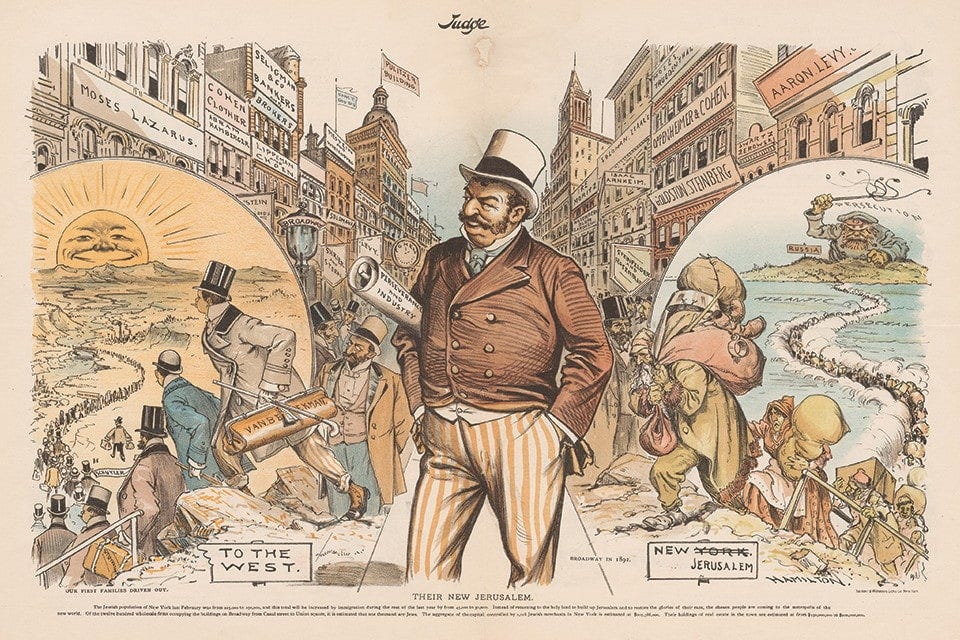

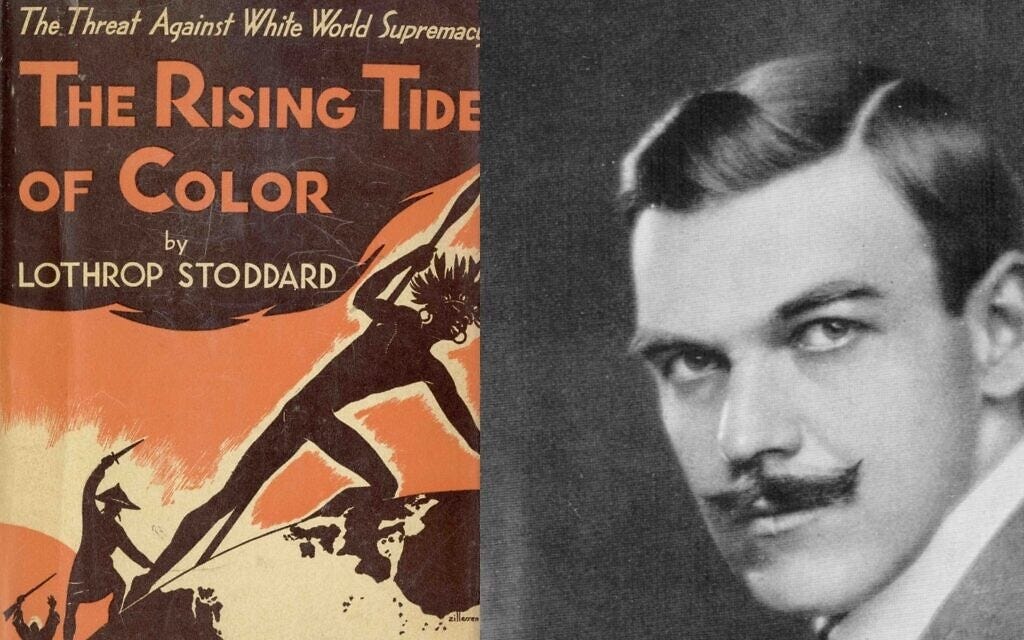

These concepts are old—accusations of Jewish control dogged the civil rights movement from the outset. One very early proponent of what would go on to become “great replacement theory” was the eugenicist, Ku Klux Klan member, and distinguished author Lothrop Stoddard. In his 1921 book The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy, Stoddard lamented that the “great Nordic race” was being “crowded out with amazing rapidity by swarming, prolific aliens,” among them the “round-skulled Jew” and the menace of “Negro fecundity.” (Stoddard absolutely looks like a close friend of Snidely Whiplash, an amazingly evil-looking dude, which is doubly apropos given his fixation on phrenology.) In particular, Stoddard’s anxiety about the alleged threat of Black birthrates mirrors quite precisely the concerns of a teenage shooter a century later: the notion of being outbred and overrun is at the core of white supremacist violence against minorities. What distinguishes racist thought in 2022 from centuries of violent anti-Blackness is only the speed and breadth with which such ideas can be disseminated; bigotry is remarkably consistent across generations, and the memes and screeds that bubble to the surface of Internet swamps like 4chan are little more than pastiche of what came before. Their power remains in their emotional appeal—the story of the Jew and his puppets and the lonely nobility of the fight for white survival.

It would be comforting to declare this a form of derangement, to dismiss the white supremacist movement and its echoes in mainstream rhetoric as fundamentally alien, or a sign of mental illness. But even a cursory examination of the discourse skittering across the Web, perpetually available to the eager and the cruel, the lost and the lonesome, reveals that it is a coherent—if monstrous—worldview, one that draws in adherents through a combination of raw emotion and pseudo-intellectual assertion. In order to combat the threat, we must appreciate that it operates as a coherent ideology, a warped lens through which the entire world can be examined. Only then, without minimization, and with recognition of the way hatreds intertwine to form a caustic whole that presses towards violence, can we begin to repair the damage it leaves in its wake.

Author’s Note:

I love writing this newsletter, and I love the independence and freedom to choose my own topics this platform offers me, without being tethered to the churn of the news cycle. However, in order to keep it sustainable, I need more paid subscribers. If you’ve enjoyed the content thus far, want to toss a coin to your witcher, or feel that submerging my head in the acid of far-right nonsense deserves some compensation, please consider a paid subscription. I’ve lowered prices for the next three months to $5/month, though there are options to pay more if you like and want to support the endeavor!