"You Have To Kill Mom Every 20 Years": How To Be A Feminist in 2023

A conversation with the Guardian's Moira Donegan about the crisis in American feminism

It’s been a year since the landmark Supreme Court decision that overturned Roe v. Wade. It’s been a terrible year for women in America — a year of increased maternal morbidity and mortality, of upended lives, of fatalities, lost lives and lost futures. In light of all this pain and grief, American feminism is undeniably in a moment of crisis. Women’s rights are being stripped away at a frantic pace by aspiring theocrats, and the response from moneyed, centralized institutions — from national feminist organizations to politicians — has been anemic at best. As someone who’s identified as a feminist my entire life, I’ve been struggling to understand how we came to this place, and where we go from here. How to take back our bodies, futures, and our equality.

To help me wrap my brain around these questions, I called up Moira Donegan, a leading feminist intellectual whose work I’ve long admired. Moira is an opinion columnist covering gender and politics at The Guardian, and writer-in-residence at Stanford’s Clayman Institute for Gender Research. We wound up going deeper than expected, and this will be a two-part column, exploring lessons from feminism’s past and possibilities for its future.

TL: So where to begin? It feels really fucked up to be a feminist these days — I guess it always has — but are there some specific things crowding the top of your mind when you think about it like,” okay, I’m a feminist in 2023? What does that mean, and how do I live that?”

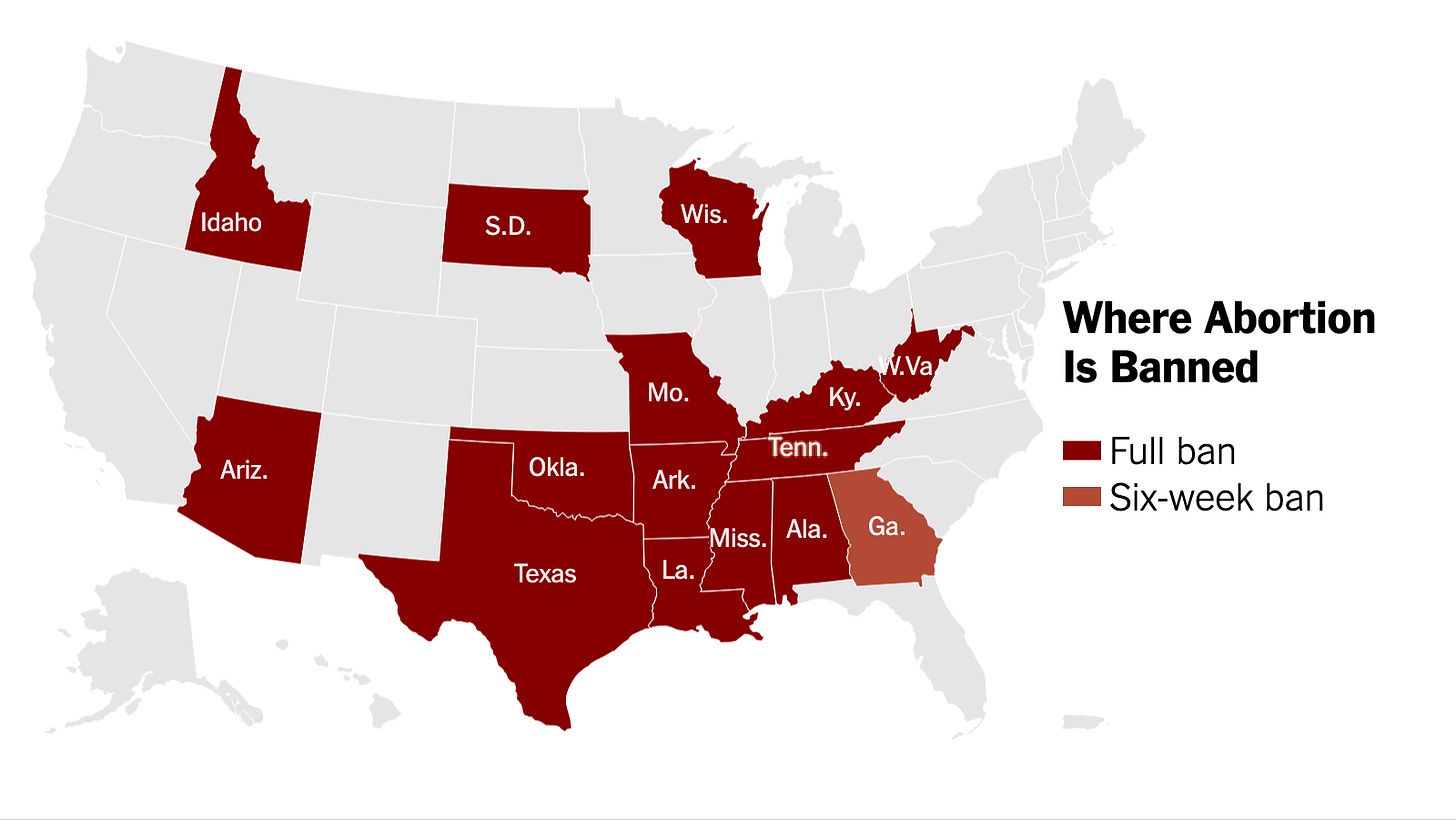

MD: For me, as somebody who writes about gender and politics, there are a few things front of mind, the first of which is obviously Dobbs and this massive lack of women’s rights around reproduction in healthcare. That is the culmination of a 50 year project, which has very radically constrained the possibilities of American women’s lives. And it’s going to have society-altering implications for decades to come.

That’s always the first headline. It’s a seismic generational change. I think Dobbs and the anti-abortion movement has become a sort of litigation and legislation template for the anti-trans movement, which is really kind of continuous with anti-feminism.

And I think this is part of a much broader movement to legally and socially curtail the possibilities of life, and to try and narrow the possibilities for what kind of life somebody can lead — what kind of things they can do, what kind of social positions they can occupy — and to narrow those specifically based on their assigned sex at birth. So you see the anti-trans movement just cribbing notes from the anti-abortion movement. “Okay, let’s start with children. Let’s talk about extremism in healthcare. Let’s use a lot of really graphic imagery.” If you look at anti-trans propaganda, and I don't recommend doing this, but there is a lot of …

It’s omnipresent.

Right. If you look at the stuff that they’re producing, not just for the public, but for their in-groups — which I did for a little research project a few months back — there were a lot of really gross visuals, descriptions and photographs, exploiting people's bodies in ways that are very cruel. And a lot of attendant language about the mutilation of children. If you take out the objects in the sentences, it’s just like what they say about abortion. So it’s sort of a legislative and a cultural strategy that’s almost identical, just imported into this new victim target group.

But it’s moving much faster than fifty years. Of course it takes less time to codify legislation when you don't have a Supreme Court decision to chip away at, I guess.

Yeah, but they’re learning the lessons about what’s worked. The thing about the fifty-year campaign against Roe is that it incorporated a lot of data. These people are nothing if not creative, and they have been throwing different strategies at the wall to see what sticks for a very long time, and making rhetorically different, sometimes quite contradictory, efforts in attempt to persuade both the public and the courts. And they have a pretty solid handle on how to manipulate information, how to manipulate public opinion, and really how to manipulate a judge. So part of it is that they can do it faster with trans rights just because they know exactly how to do it.

With abortion, limiting access to forms of medicine that allow people to break out of a gendered role is something that they have a profound amount of experience doing, and a lot of expertise.

But, to your point, culturally it is easier to move the needle on anti-feminist gender-conservative agendas because our media has changed. Politics moves faster now because we have the internet; it used to take a long time to slowly create cultural permission for public misogyny, or to slowly poison the well against feminists with these caricatures of them through traditional media. You needed a lot of money, you needed a lot of access to power, you needed a lot of time. And now you can coordinate a trolling campaign on Reddit with unpaid ideologues and cheap bots, and you can make that happen pretty quickly. And because of the iterative aspect of social media, you can get a lot of people who aren’t involved in your coordinated effort to take up that goal, and propagate it elsewhere, like the way a mushroom spews spores out and then creates more mushrooms. That's very easy to do with the right-wing agenda.

You also see it with these anti-queer boycotts — the seed was planted very quickly, and it grows very quickly. And just by having a few loud actors you can create a sense of a much wider mobilization, or a much deeper depth of animus than perhaps actually exists, because it’s easier to coordinate a lot of people.

I’m looking at this seismic rollback of bodily autonomy for women, but I don't see a seismic social counter reaction of analogous force and conviction.

The Biden administration is not acting on it at all, not that political parties have ever been the driving force for activism, but the Democrats were like, “we have this purported set of values,” and I guess it’s just gone now.”

Okay, but what happened? Like, of course we live in an openly misogynistic, cruelly misogynistic society; there’s are so many reasons a feminist movement gets chipped away at, eroded. But where is the countervailing force? Are we all just going to atomize and suffer on our own? How do American women regain our freedoms, or fight for our freedoms en masse? Is that a possibility? What does that look like? Where is it? Like, get me out and on the street, you know? I'm donating to abortion funds, and they're amazing. But it just feels like there's this massive hand striking us down and where's the responsive countervailing movement?

I think you're speaking to something really real and very frustrating, which is that — in the US in the 21st century — there is an enormous amount of popular feminist sentiment, and no national feminist movement. There just is not a national organization meaningfully making a dent in this. There is not a very public, very visible movement leadership around women’s rights in a way that people can point to and say, “these are the leaders.”

And there are a few reasons for that. A lot of civil society and left-wing groups were really gutted during the Reagan administration, and have never egained their footing. The National Organization for Women — which was the big liberal liaison between feminists and the Democratic Party — now they’re basically just a fundraising outfit for the Democratic party.

The National League of Women Voters, I think, is similar.

Yeah. I don’t want anyone to yell at me, but these are not organizations with meaningful grassroots organizing efforts. Planned Parenthood had a similar story after [landmark Supreme Court Case Planned Parenthood v.] Casey; operating costs became so massive. They had to be both a national network of clinics and also this really huge law firm, basically. And they are not equipped to organize around women’s healthcare needs and women’s civil rights in the same way that we would maybe want them to.

And this is not unique to feminism. This has happened with some of the major Black liberation organizations. It’s sure as shit happened to unions. And at the same time that these institutions have been degraded, the possibilities for grassroots organizing around these liberation issues have been chipped away. It’s really expensive. The cost of living is much higher. People have way fewer places where they can gather in large groups in person regularly, and they have less free time because you have to work three jobs just to fucking stay alive. It’s really, really hard to organize around this kind of stuff, but it’s not impossible.

Something else I’ll say is that feminist sentiment tends to disappear into other coalitions. There’s a lot of people who identify as feminists, but when they are working on behalf of that, it might be through a neighborhood organization, or a mutual aid group, or a very local abortion fund, or an immigration advocacy network. So a lot of the grassroots organizing that does aid the cause of women’s freedom is not necessarily labeled as feminist.

An interesting question is “why?” Why is feminism not a central and rallying political identity for so many people, young women, young people? Right now, it feels like the only people who are using that framework, who are like, “we're feminists protecting the rights of women,” are TERFs [Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists, a hate movement] who are allied with Nazis and are deeply oppressive people.

I don’t think they’re the only ones, but they’re definitely very visible. The thing about TERFs is that it’s like 500 people, they’re all white British women, and they are made hyper-visible because they have all this fucking Heritage Foundation money. So terfs are noxious and they’re loud, but not even a huge contingent within transphobia. Like, transphobia is a big umbrella of hatred. And there are these people who have a nominally feminist rationale for their transphobia, and decide to spend their whole day getting mad about college women’s swimming. I’m like, “no, I’m more concerned with people bleeding to death in their houses.”

I don’t wanna spend too much time on TERFs because I think we can both agree that they're just garbage.

As somebody with an investment in the radical feminist tradition — to the extent that I’ve built my life and career around it — they really, really get me riled up, man. I could spend all day talking about these people, but they’re insincere and they’re few and ultimately I think they only really matter in proportion to how much attention we give them.

So who are some radical feminists of the past that we can look to now for inspiration?

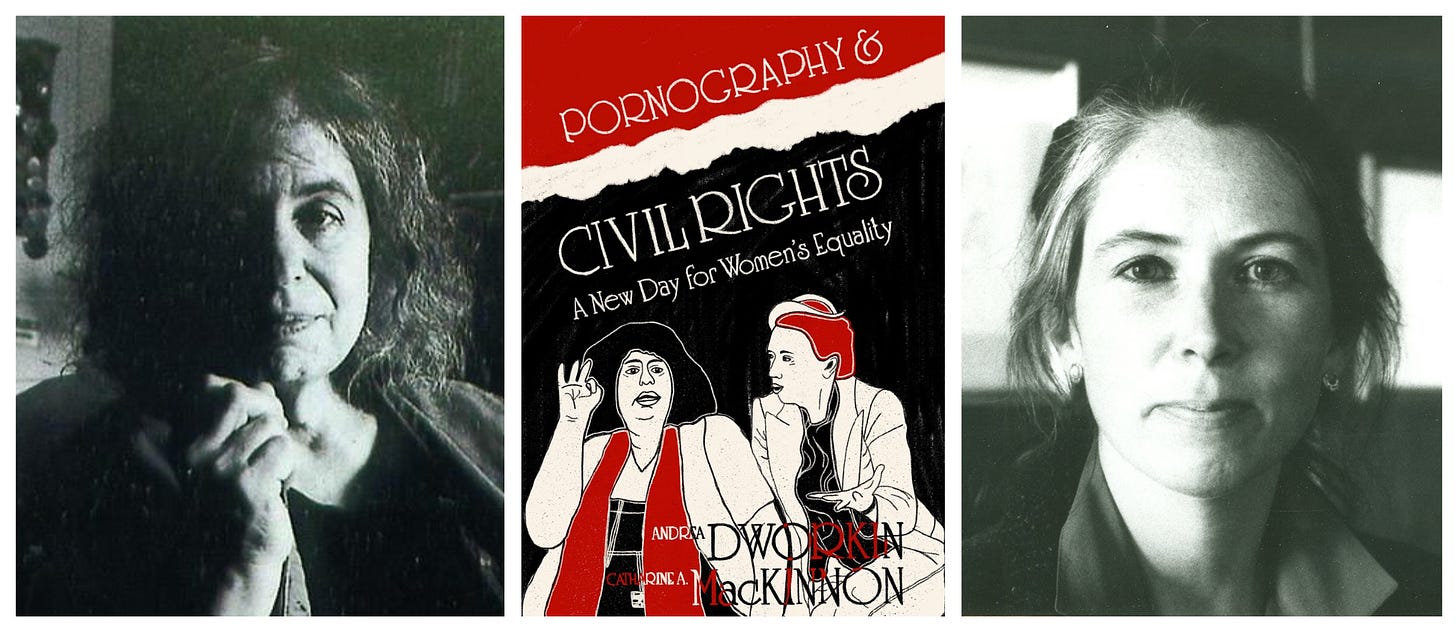

You know, I think it was an understandable mistake for feminists of the nineties and aughts to sort of try and disavow the second wave. Because that is a generation of thinkers who disagreed with each other on a lot, but who are coming from a tradition that took the question of women and their liberation very seriously. I’ve taken a lot from my readings of the second wave. It is really useful to read Kate Millett, and it was useful to read Catherine McKinnon and Andrea Dworkin — not that I think you have to take it like the Bible.

Another problem of feminism that really stuck with me when I went back and read the big feminist texts of the late sixties and the early seventies: these are fights that we are now having in 2016, 2017, 2020. And because of this idea that we have to kill mom every twenty years, and disavow the mistakes of the past by completely abandoning the work of those generations of thinkers, we get stuck in a repetitive cycle of reinventing the wheel. Don’t discard everything from people who were wrong or misguided or stupid about some stuff, and don’t disregard everything that comes from a generation that lived under different circumstances than yours. Because I think history is actually very instructive here in terms of why young women don’t identify as feminists. There’s a degree to which TERFs and their huge visibility have really spoiled the label.

I have absolutely no interest in re-litigating the 2016 or 2020 primaries, but I think for people in our very specific milieu — millennial intellectuals — that turned a lot of people off of the label. And that there have been some weaponized misreadings of intersectionality that have been meant — not to expand and complicate the concept of misogyny to give it more explanatory power and over how it impacts the lives of like people of color — but actually to misuse intersectionality to diminish the idea of misogyny as its own axis of oppression. Those are some intellectual trends that have damaged feminism as a political identity.

But that’s a branding problem. I think that a lot of people are really outraged by this anti-trans shit. People are really outraged by the anti-abortion shit. And people are more uncomfortable than it might be publicly suggested with the third prong of the anti-feminist backlash, which right now is anti-Me Too.

It's all very interconnected — you see antifeminism manifest in all sorts of ways, like the notion that all kids should be homeschooled — the current wave of anti-public school sentiment is very tied up with the idea that women should be in the home.

The Christian push against public schooling is part and parcel with, like, “keep your kids from being exposed to role models in teachers, administrators, other adults outside the home who might model different ways for women to live, and give them resources and connections outside of that.” It’s a very insular, often quite abusive, and sort of hyper-Christian homeschooling zone.

It’s very rare that I talk to someone who’s a scholar of feminist theory in the way that you are, so I want to talk about specific experiences I had, but then turn to you and ask if my impressions are correct about a broader social trend.

I grew up with a religious feminism that tried very earnestly to make space for women within Orthodox Judaism, a deeply misogynistic religion. The ways that feminism manifested were about creating separate spaces, parallel spaces, that were in backyards and basements, not in synagogues, not in officially recognized congregations. I recited my bat mitzvah Torah portion in my backyard, in front of only women, instead of in front of the congregation like every boy — and it was very unusual that I even did that.

And in the much broader, wider world, my impression of the feminism of the period is that it was all about these types of compromises, like — we’ll work within externally imposed limitations, and not stridently demand equality or acceptance, necessarily. And it felt like feminism of the nineties and early aughts became a bit defanged in that sense.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about serious extremism and equally serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription:

My study of feminism and my own intellectual tradition proceeds from the late seventies to the eighties: radical feminist reading that really defines the issue at play as eradicating the violence and indignity that women endure because they are women. And you can extrapolate a lot from that. Getting rid of that will necessarily do quite a bit towards the rights of gay men and trans people who are not women, but I think it’s actually a fairly expansive but quite well-defined project. And what happened in the nineties and the aughts is that during what Susan Faludi has called “the backlash era to feminism,” there was an attempt to create, due to the quite virulent misogyny of the 1980s and 1990s, a version of feminism that would be palatable and workable in that era. To a degree, I think they were trying to cut their losses.

My mother did not identify as a feminist even though she was a single mom who had been to grad school and was running her own business. A lot of what you heard during that era was, “I’m not a feminist because I don’t hate men.” Or sometimes, “I’m a feminist but not a lesbian.” That was a big one. Like, some of us are lesbians, sorry. But it was a very defensive stance, and it was defining itself specifically against the Andrea Dworkin image, because that was not an assimilative image.

It was a Jewish image. Sorry, I just feel like I had to say that.

Oh, yes. And Dworkin has written very interestingly about the intersections of misogyny and antisemitism.

But it was also against the rhetoric of Katherine McKinnon, who was like a wild wasp, you know? It was an attempt to create an image of feminism that men liked, and that meant a few things. It meant emphasizing the half of equality where women take up equal burden, where men give up what might have been traditional obligations. It meant accessing or emphasizing the kinds of sexual freedom where men can have greater sexual access to us. It did not emphasize the kind of sexual freedom where I actually retained the right to say no at any time under any circumstances. So it was a kind of feminism that was: “We are sex positive women, we are independent, we remain very feminine, we are thin, we wear high heels and lipstick and we use our sexuality to get ahead in the workplace.” All these things that men like, as an attempt at a bargain: “You won’t have to provide for us. We will keep fucking you. We will keep looking the way you like us to look. We won’t be angry. We will be nice.” And this is how we will get a degree of more freedom.

And, look, there’s a degree to which it worked. Women’s workplace-participation peaked in like 1999, and has been going down since, and the wage gap shrunk. But it also meant that feminism no longer quite meant a political movement for the abolition of the oppression faced by women because they were women. Feminism now meant femininity, or it meant anything that a woman ever does. It just meant girls. And it didn’t mean girls fighting to take their equal place in the world. It didn’t mean full rights and dignity. It didn’t mean men had to give anything up.

And that was a kind of feminism that could be very palatable but also didn’t really mean anything, so it was very easily co-opted. It was very easily commercialized. It was very easily claimed by people who didn’t have much of a principled opposition to misogyny. And that did alot to erode feminism’s brand.

But it also meant this flip side for women our age. I grew up hearing that girls can do anything. And for a long time I fucking believed it. Then I grew up and I had to be a woman in the adult world, and it turns out girls can’t do anything, and girls don’t have equal dignity with men. Girls are cut off from a lot of different opportunities, a lot of social roles, a lot of sources of equal citizenship and equal esteem. And that has only gotten more constrained as I have gotten older. So for me it has felt like feminism is becoming more urgent. It feels like there is an emergency. But at the same time, feminism has gone through this legitimacy crisis and can’t recruit. And that’s a real fucking cul-de-sac, man. I don't know how exactly we get out of it.

This is absolutely 🔥🔥🔥(and got me to finally get around to subscribing). I got goosebumps reading it.

"It didn’t mean men had to give anything up."

The zero-sum mindset that seems to pervade our society is so disappointing. It is such a tell when people feel like they will lose if they have to value the human dignity of every person.